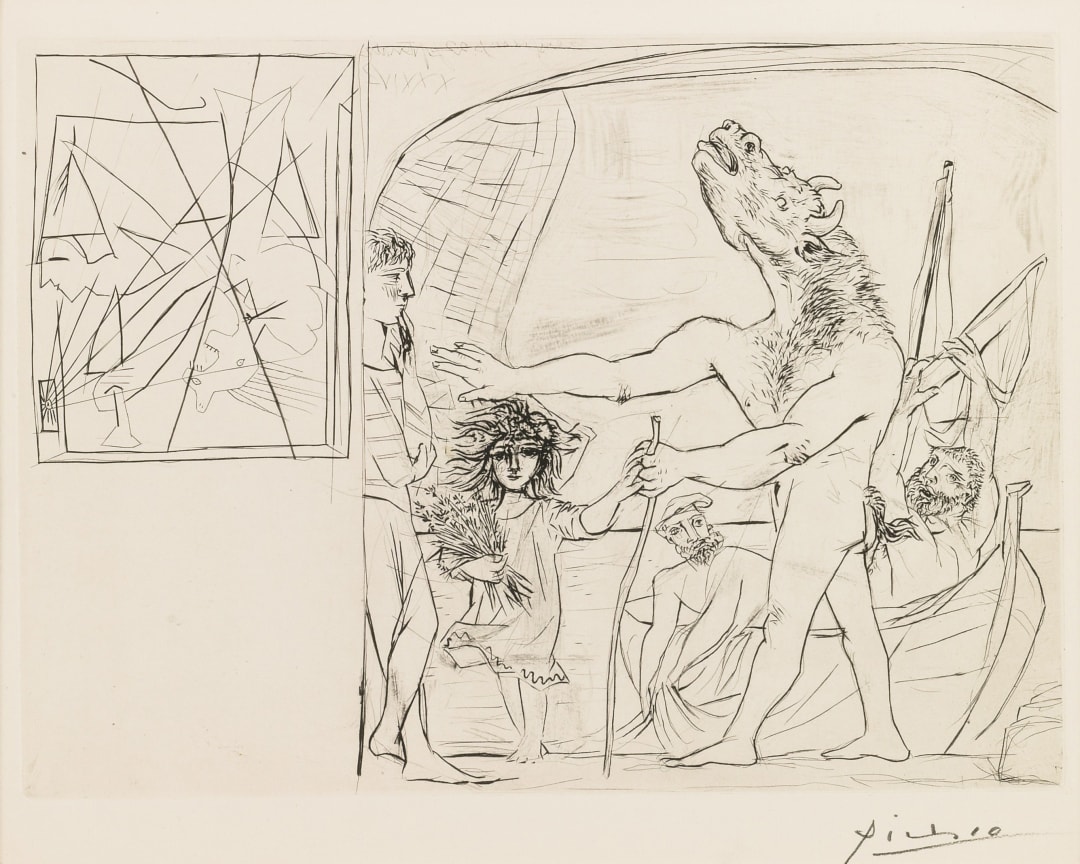

The four plates that comprise the “Blind Minotaur” series within the Suite Vollard, a subset of the fifteen Minotaur images, are among the most fascinating prints in Picasso’s oeuvre. Though they share the same elements—the blinded mythical beast, a young girl who resembles his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, a passive young sailor, and a sailboat with two fishermen—each is a distinct exploration of the theme using varying techniques, symbolism, and modes of representation.

Picasso conveys a sense of chaos and emotional desperation in these powerful prints; the tables have completely turned on the lovers who cavorted, relaxed, and swooned in the “Sculptor’s Studio” and “Minotaur” etchings. Here, the sculptor/Minotaur, who once dominated the relationship, is helpless and blind. The sensual and submissive model is now an innocent and self-assured little girl who leads him through a complex landscape near the shore, in both day and night, fair weather and foul. Though he was a fearsome beast in earlier plates, the Minotaur is regarded with a look of concern and pity from the sailors he passes. Likewise, the viewers are moved to pathos for this mythical beast that once provoked disgust.

Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer argues that Picasso’s Blind Minotaur is in fact a conflation of two myths: Oedipus and the Minotaur (Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection, Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, 89-91). Oedipus, of course, blinded himself after learning the truth about his incestuous relationship with his mother. Here, the Minotaur is equally maimed by the guilt of his extramarital affair. His mistress Marie-Thérèse, who is now a little girl, takes the place of Antigone, Oedipus’ daughter who led the sightless king to Athens, where he would die in Theseus’s arms (interestingly, the deaths of both figures were attended by Theseus, the founder-king of Athens, who slayed the Minotaur and provided solace to Oedipus in his last days). The combined symbolism suggests that Picasso intuited that his relationship with her would result in a death of sorts, and indeed, within a year his life changed completely.

This iconography of the “Blind Minotaur” series has been analyzed at length in terms of Picasso’s life at the time it was created in late 1934. His long-term affair with Marie-Thérèse was beginning to disintegrate and she would soon reveal to him that she was pregnant (according to Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer, she informed him just before Christmas that year). Picasso was in his mid-50s and was likely experiencing a sort of mid-life crisis. He had been struggling with self-doubt as a result of a lukewarm critical response to his mid-career retrospective in Paris and Zurich in 1932. His relationship with his wife, Olga Khokhlova—a former ballet dancer from Ukraine—was extremely strained and had been so for years. Khokhlova suffered from anxiety, which led to frequent emotional outbursts, and also was extremely jealous and possessive. Picasso found her behavior unbearable and sought out Marie-Thérèse’s company as a respite from his wife’s tantrums, even installing Walter in an apartment across the street. Yet he feared the wrath of his wife if they should be discovered. The deception and complexity of his situation was clearly another source of stress for the artist. Clearly, Picasso was beginning to feel that the situation was out of his control and this comes through strongly in the images.

The presence and inspiration of Rembrandt on Picasso’s work can be seen in the iconography and technical brilliance of the “Blind Minotaur” images (in addition to a number of other plates in the Suite Vollard). As noted by scholar Janie Cohen, Picasso was intimately familiar with Rembrandt’s work in both painting and etching, and borrowed from his work on several occasions, creating his own versions of iconic themes and subjects treated by the old master (“Picasso’s Dialogue with Rembrandt’s Art” in Etched on the Memory: The Presence of Rembrandt in the Prints of Goya and Picasso. V+K Pub./Inmerc.: Blaricum, The Netherlands, 2000, 80-1). Both Cohen (ibid., 86) and art historian Lisa Florman see a resemblance between Picasso’s sightless beast and Rembrandt’s Biblical figure in The Blindness of Tobit, 1651 (Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2000, 151-2). The two figures share a similar pose, a walking staff, gaping mouth, and groping gesture.

Rembrandt’s position as the undisputed master of etching is known to have been a source of competitive drive for Picasso—while discussing a particular plate in the Suite Vollard with his long-time dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Picasso once said, “Now I’m going … to see if I can get blacks like [Rembrandt’s]—you don’t get them at the first try” (as quoted by Hans Bolliger in Picasso’s “Vollard Suite,” Thames & Hudson, New York, 2007 [reprint of original 1956 edition], xii). Picasso’s playfulness with the intaglio medium and his technical ambition in the four “Blind Minotaur” prints was also probably motivated by his desire to reach a level of proficiency with intaglio that equaled that of the Dutch artist. In service to his goal of becoming a great etcher, Picasso developed a close relationship with the exceptionally skilled intaglio printer Roger Lacourière at this time, whose advice on technical matters had an immense impact on the artist’s development in the medium. Following on the four prints of the “Blind Minotaur” series, Picasso created his master intaglio plate La Minotauromachie (Bloch 288)—a variation of the themes he explored in these etchings. It is in the process of creating these four plates that Picasso takes the final step toward his goal of becoming one of the most important and accomplished etchers in history.