In July 1945, in conversation with the Hungarian photographer and writer, Brassai, Picasso said about one of his paintings: “If it were possible, I would leave it as it is, while I began over and carried it to a more advanced state on another canvas. Then I would do the same thing with that one. There would never be a 'finished' canvas, but just the different 'states of a single painting, which normally disappear in the course of work.”* In November of that same year, Picasso entered Fernand Mourlot’s print shop in the Rue de Chabrol and took on lithography as a new creative endeavor. It seems that, with this medium, Picasso discovered how to actually practice the concept he had described to Brassai just a few months ago.

Picasso’s body of lithographic work before this time wasn’t large or substantial. But he certainly made up for any lost time once he began his collaboration with Mourlot. The artist was entranced with the medium— working twelve-hour days if not more, without interruption, his time commitment was matched by his ability to break from traditional techniques in order to push the boundaries and limitations that existed before him. The craftsmen at the workshop were astounded by Picasso’s dogged determination. Of course, in comparison to etching— where making changes on a metal plate is extremely laborious, erasing the surface of a stone is much easier. Picasso being Picasso though utilized this ease to the point where it became just as challenging. In other words: even the printers didn’t think it possible to push the medium that far.

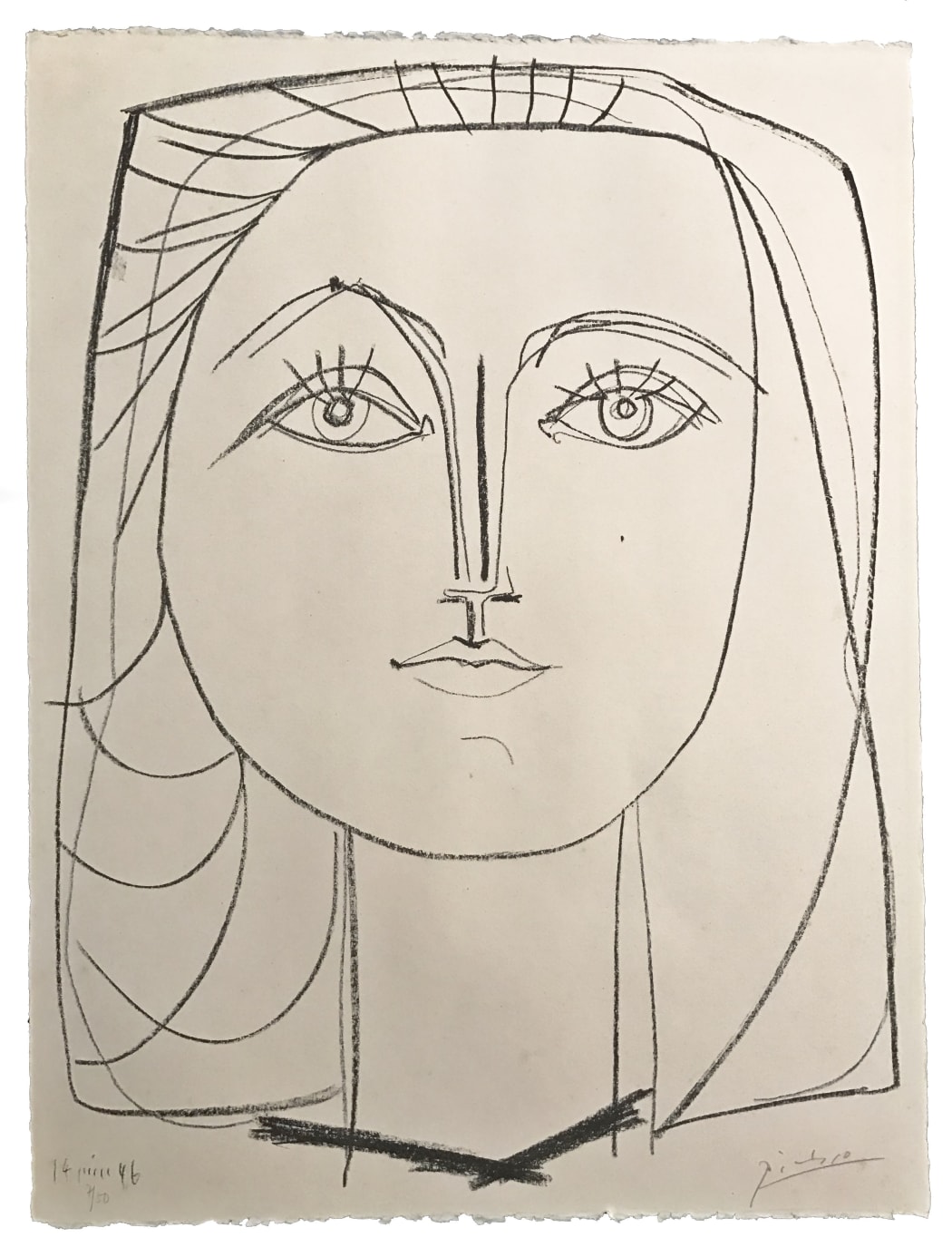

Françoise aux Cheveux ondulés (Bloch 403), 1946, lithograph, 25 x 19 inches

One particularly astonishing result from this burst of creative activity: A series of nine lithographs of which eight were done in one day, and the ninth done the next day. Created in 1946, the subject is Picasso’s lover at the time, Françoise Gilot. They are all portraits of her face, and they are all made up of elegant mostly simple lines, yet each one is unique and expressive in its own way. These lithographs show the progression and transformation of a single idea as it’s being thought about. It’s no wonder Picasso worked so tirelessly— he finally found a way where he could tell the type of story he wanted to. A story that has as much to do with its subjects as it does with the artist’s process. Gilot, on explaining Picasso’s passion for lithography, recalled him saying, “I’ve reached the moment...when the movement of my thoughts interests me more than the thought itself.”**

In collaboration with Mourlot, Picasso wound up producing around 350 lithographs in under two decades. Gilot was the subject of many of them. We talk about muses often; the roles they play in the artist’s life and work. It’s interesting, then, to think about a medium in the same way you think about a muse: The discovery, the initial infatuation, the exploration. Picasso found something in lithography that he hadn’t found anywhere else. As a result, he immersed himself in it completely. When he moved to the South of France in 1959, Gilot had left him several years before, and the far distance from Mourlot’s studio made the logistics too complicated. In a new place with a new love (Jacqueline Roque), Picasso had to seek new ways to the artistic stories he wanted to tell.

* Lavin, I. Picasso’s Lithographs: “The Bulls" and The History of Art in Reverse. Institute for Advanced Study. December 2009.

** Gilot, F. Life With Picasso. 2019. New York Review of Books.