Last week, we took a brief look at Edvard Munch’s early days of printmaking, focusing on the 1894 drypoint Trost (Consolation) (W6). We looked at this drypoint because captures the way he used printmaking to express deeply human emotions in completely new ways. How was it that Munch-- known for revisiting the same motifs and themes time and time again-- was able to breathe such new life into each work?

As we mentioned last time, the artist was able to reach a much larger audience with prints than with paintings. Unlike paintings, which were laborious and resulted in one final work, prints had the capacity to produce editions of multiple impressions, thus expanding the artist’s accessibility to the public while also allowing him to alter the imagery in different ways. But reaching a lot of people wasn’t nearly as intoxicating as what the medium had to offer artistically. In those early day, Munch approached prints with the utmost experimentation. He didn’t yield to limitations set by others, he didn’t follow anything formulaic. Munch (much like our friend Picasso), is often given credit for his quick mastery of grasping and commanding printmaking, which he did. To say that this quick mastery is what makes him significant, though, is almost missing the point. For it was Munch’s neglection of “connoisseurship” and the status quo that allowed his prints the physical rawness needed to capture such startling emotions.*

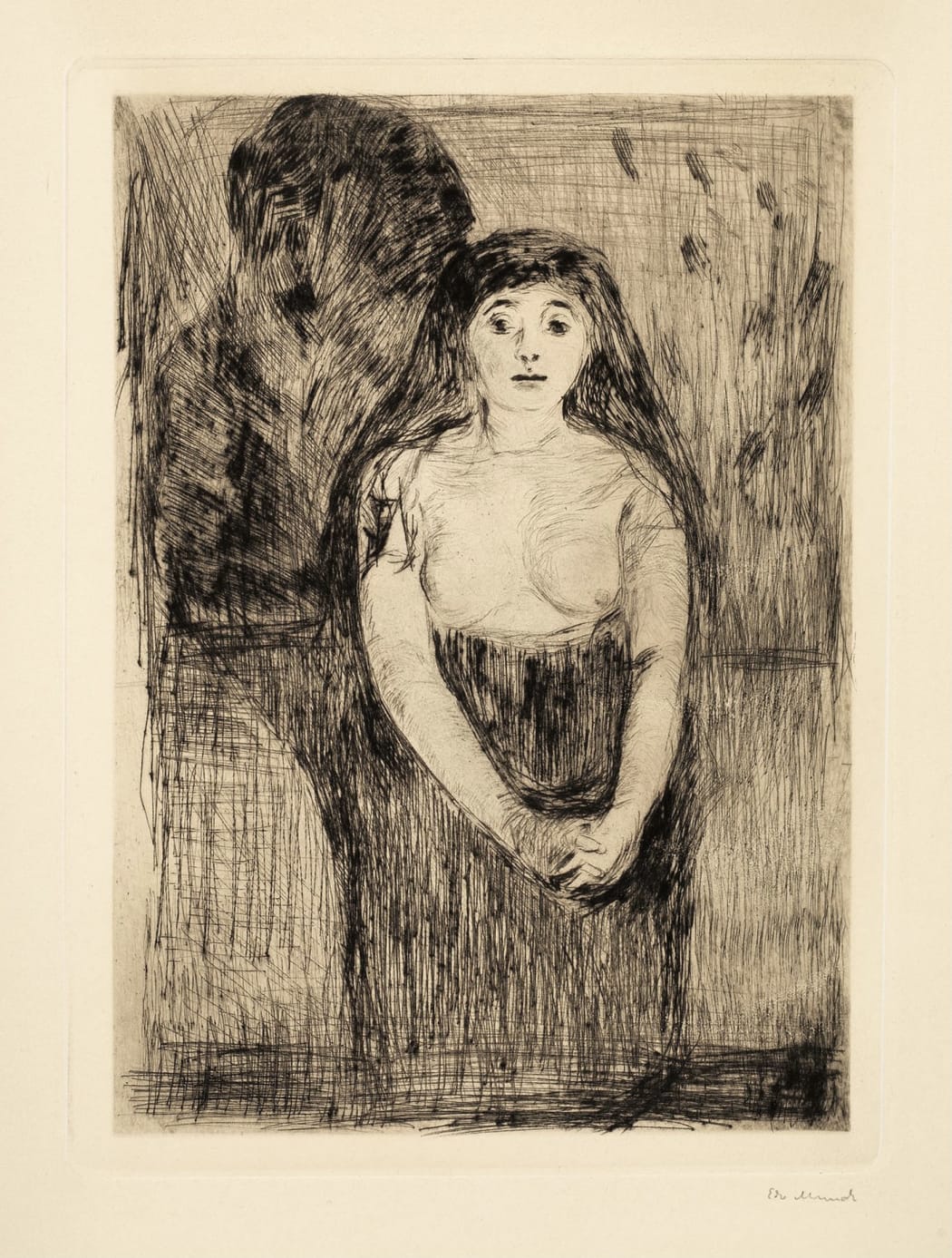

Modellstudie (Study of a Model) (Woll 8) (state III), 1894, drypoint, 11 x 8 1/4 inches

Munch perhaps described the goal of his art best when he wrote, “It's not the chair that should be painted, but what a person has felt at the sight of it."** If the use of a chair seems arbitrary, a quick refresher: One of Munch’s first memories was of his mother before she died of tuberculosis when he was just five, sitting at her chair at their home in Kristiania and gazing out the window onto the fields. In case there needs to be any more clarification that Munch put his own personal pain and haunting memories into his work, another of his quotes make this very clear, as he wrote, “...My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art."

So, undeniably Munch was intricately linked to his work in a way that was unavoidable: His stated desire was to create art that resonated emotionally. And his inability to separate his suffering from his work meant the emotions he was evoking from his viewers came directly from his own, angsty emotions. As he embraced printmaking techniques, he made it a point to cultivate human feelings instead of simply beings or objects. In Modellstudie (W8), another drypoint created in 1894, the fuzzy lines blur the model with the shadowy background. Though her facial expression is aloof and not easy to interpret, with the shadows and meshing of lines, the artist is impactful in adding an ominous depth to the print. In Woll’s analysis of the versions of Modellstudie, it seems how intentional this was. Woll notes that from state I to III, the model’s face, chest and arms become increasingly more pronounced. In state II, the shadow on the wall and the skirt are more distinct, though still faint. Finally, in state III, the face and hair are the most pronounced. The arms and chest have definition. And possibly most noticeable, lines cover the front of the bed and the skirt and the wall.*** Maybe it’s not even hard to make out that there is a room or a bed there anymore. But as Munch implied, he was not very interested in portraying a room. What he excelled at was getting to the core of the viewer. What he was able to envoke-- the true significance of his artistry-- was how the viewer would feel upon seeing the room.