The series of 15 etchings we’ve been talking about for the past few weeks was Picasso’s first major foray into printmaking and a clear indication that his ability to quickly learn and master a new medium was something extraordinary. As the name suggests, the series explores the Saltimbanques and fringe groups who inhabited Montmartre, Paris at the time, capturing those on the outskirts of society. But the name also may lead someone who’s never seen the etchings to assume they are all depictions of these circus performers. As we mentioned last week, referring specifically to Salome (B 14), this is not the case. This week let’s look at some others in the suite that don’t neatly fit the “Saltimbanques theme.”

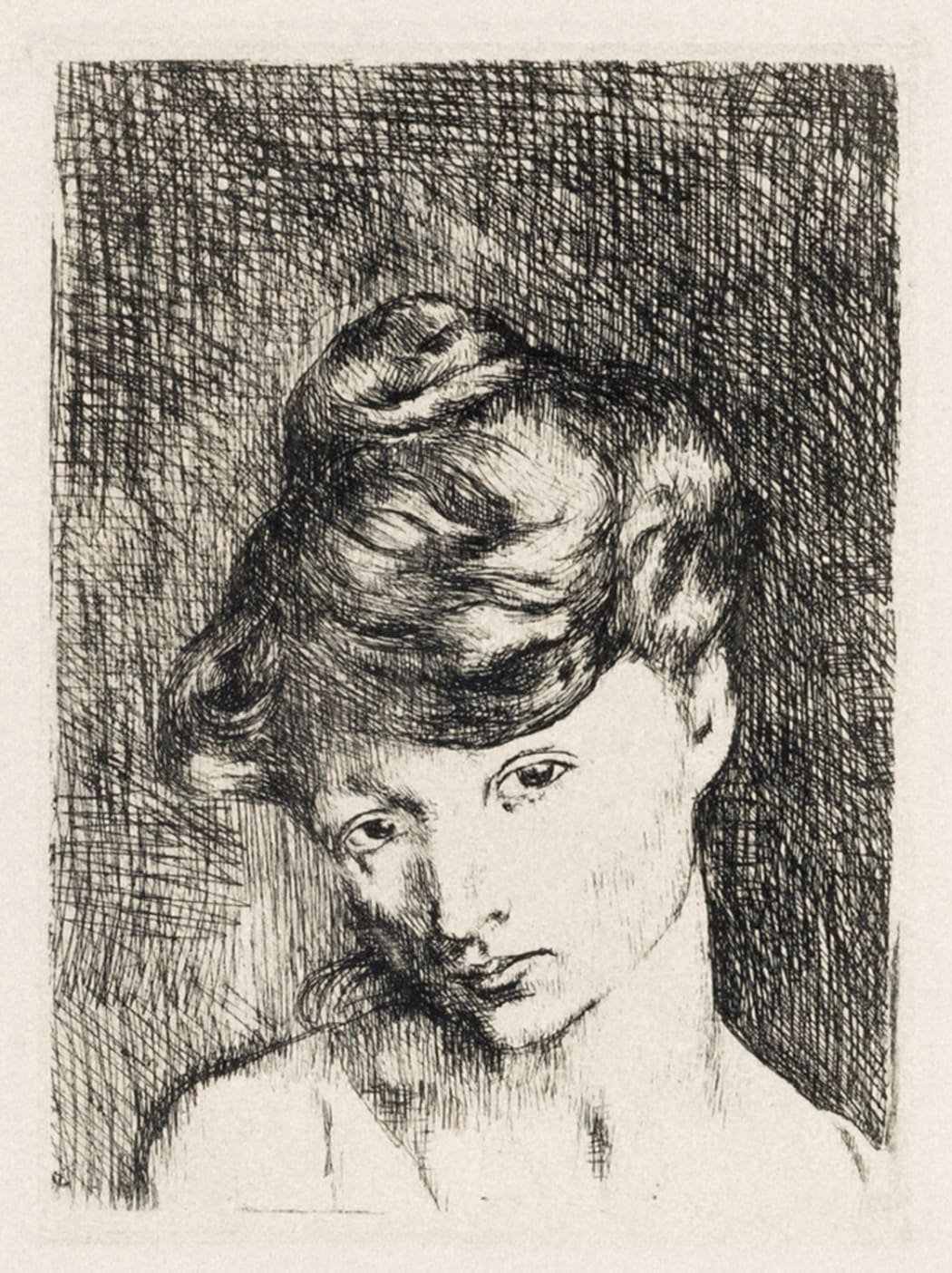

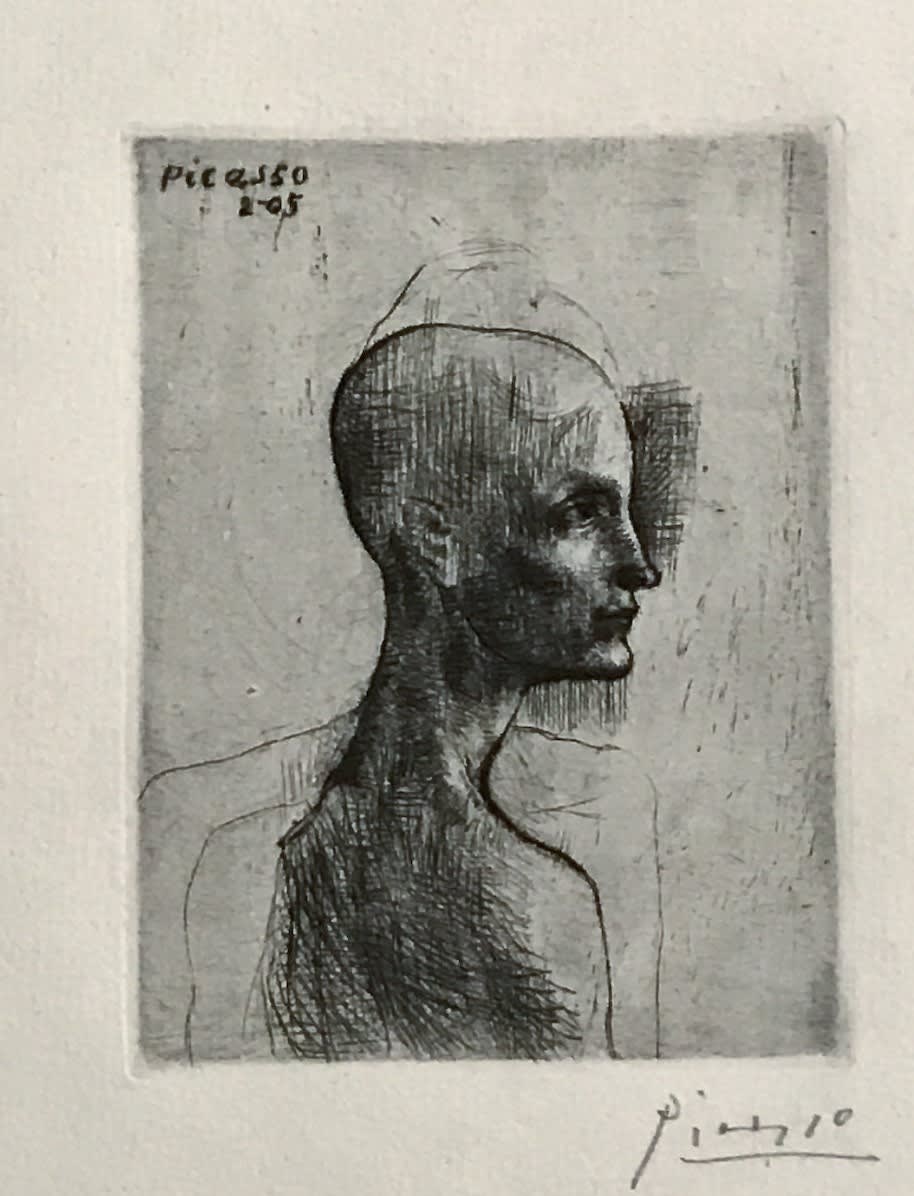

There are three portraits in the suite: Tete de Femme: Madeline (B 2), Buste D’Homme (B 4), and Tete de Femme De Profil (B 6). The portraits aren’t of acrobats. They don’t illustrate a scene of daily bohemian life like others in the suite do. Similar to the famous Le Repas Frugal, though, the details of facial expressions in these portraits show an intense intimacy— an intimacy that couldn’t have been captured if Picasso wasn’t as confident and experimental as he was in approaching printmaking. *

Buste d'homme (Bloch 4), 1905, drypoint, 4 5/8 x 3 1/2 inches

Madeleine, the subject of B2 and B6, was one of Picasso’s lovers and muses, though there is very little known about her: where she came from, where she went, even her last name. Through Picasso’s etchings of her, detailed and poetic, we get a glimpse into a mostly mysterious relationship.**

Yes, Picasso was drawn to the challenges and constraints printmaking posed. But it also made sense to him at the time because it afforded him the opportunity to express everything. Picasso was struggling at the time and creating a single painting (expressing just a single idea) could be a costly, time-consuming endeavor. A series of etchings, on the other hand, could tell a whole story. It could evoke what he was thinking, seeing, intimately feeling. It’s no wonder it became a vital medium for the rest of Picasso’s life.

So does the suite des Saltimbanques actually have an underlying theme? If it does, maybe it’s simply that intimacy. Even the etchings that are of the Saltimbanque circus performers, are hardly of them actually performing. Because Picasso was interested more in encompassing the space between their public livelihood and their personal everyday world.

Tête de Femme de Profil (Bloch 6), 1095, etching, 11 1/2 x 9 3/4 inches

Thinking about a personal diary, it’s not the particular subject matter of each days’ events that connect the diary’s entries, as every day brings something new and different— what happened yesterday can be totally unrelated to what happens today. The connection, then, comes from the person who is writing the diary, chronicling experiences and emotions that may otherwise seem completely random if they were not coming from the same person.

With the Saltimbanques Suite, we’re seeing the diary of a 23-year-old artist: The friends he is hanging out with, the new independent lifestyle he is taking on, the types of entertainment he is enjoying, the subcultures he was exposed to, and the muses he was romantic with. And similar to a diary, the works weren’t initially meant to be shared en masse. Picasso’s intention wasn’t to put them together as a suite. In fact, it was only after Vollard bought the 15 plates and titled them ‘La suite des Saltimbanques’ that they became a cohesive, and sought-after, collection. ***

*Annette King, Joyce H. Townsend and Bronwyn Ormsby, ‘Girl in a Chemise c.1905 by Pablo Picasso’, in Tate Papers, no.28, Autumn 2017

**Marlowe, Lara. “Picasso’s women.” The Irish Times, Oct 19, 1996

***Sally Foster. EARLY PRINTS BY PABLO PICASSO. Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art 2015.