Pablo Picasso’s name is so ubiquitous, even those with no knowledge of the art world know it. It’s hard then to image Picasso as an unknown starving artist, struggling to get by. But of course, Picasso wasn’t always “Picasso.” In fact, it was the bold risks he took during his formative years when he was a struggling artist, coupled with the natural talent he had, that launched him into the icon he is seen as today.

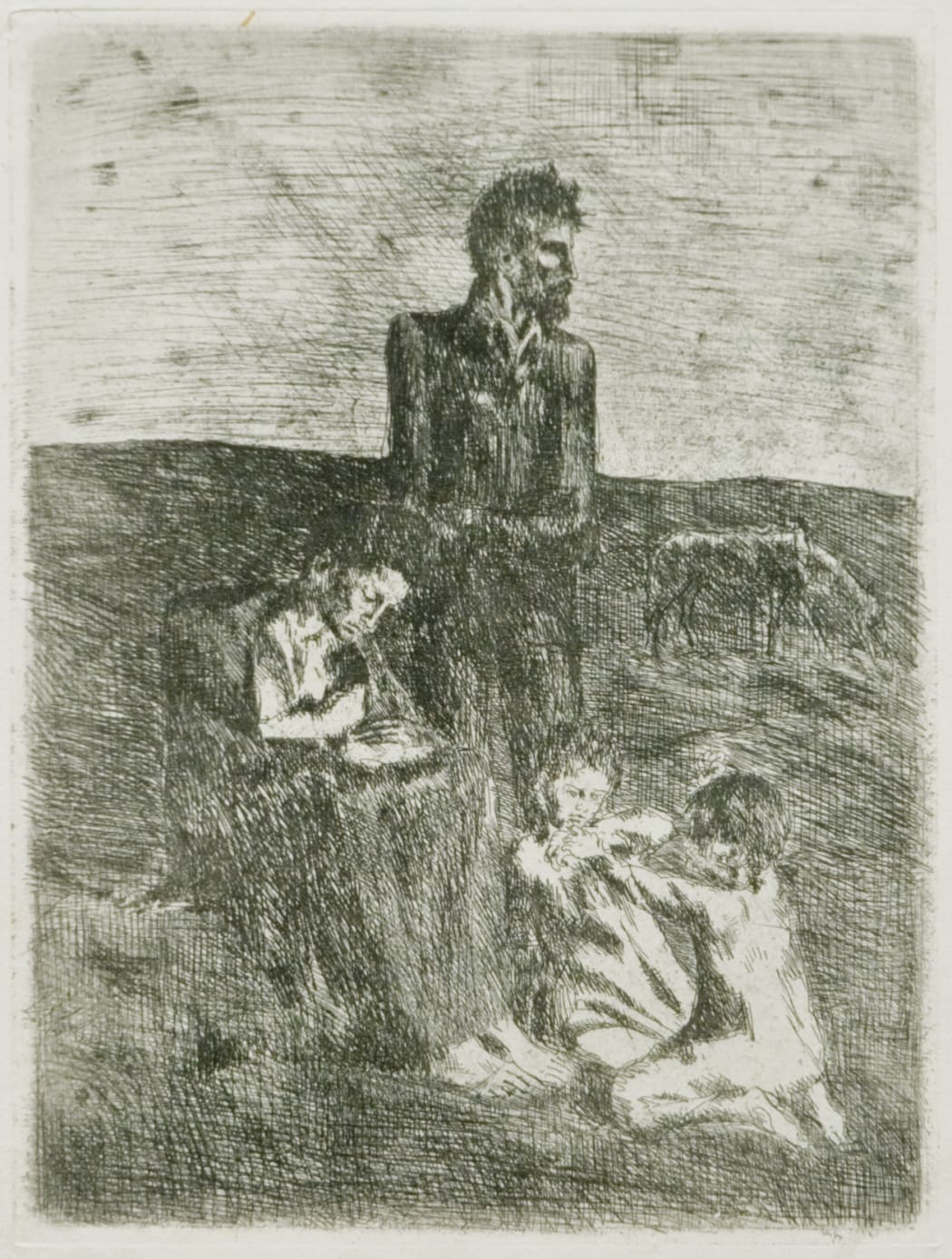

The formative years I’m speaking of are the early 1900s, and Picasso’s first foray into printmaking was with a series of fifteen etchings and drypoints known as the Saltimbanque Suite.* We’ve touched on the Saltimbanque Suite before, but now let’s dive deeper into the setting surrounding Picasso when he created this set. The year was 1904. He had recently moved to Paris and was working off little resources. Living in Montmartre, a poor bohemian neighborhood, Picasso’s subjects became the people he was among and their simple, daily experiences: Circus people, street performers, harlequins. Picasso was only 23 years old. His studio didn’t have gas or heat. Yet still, he was unapologetically experimental while embracing the new medium. And his early mastery of printmaking demonstrated just how talented he was.

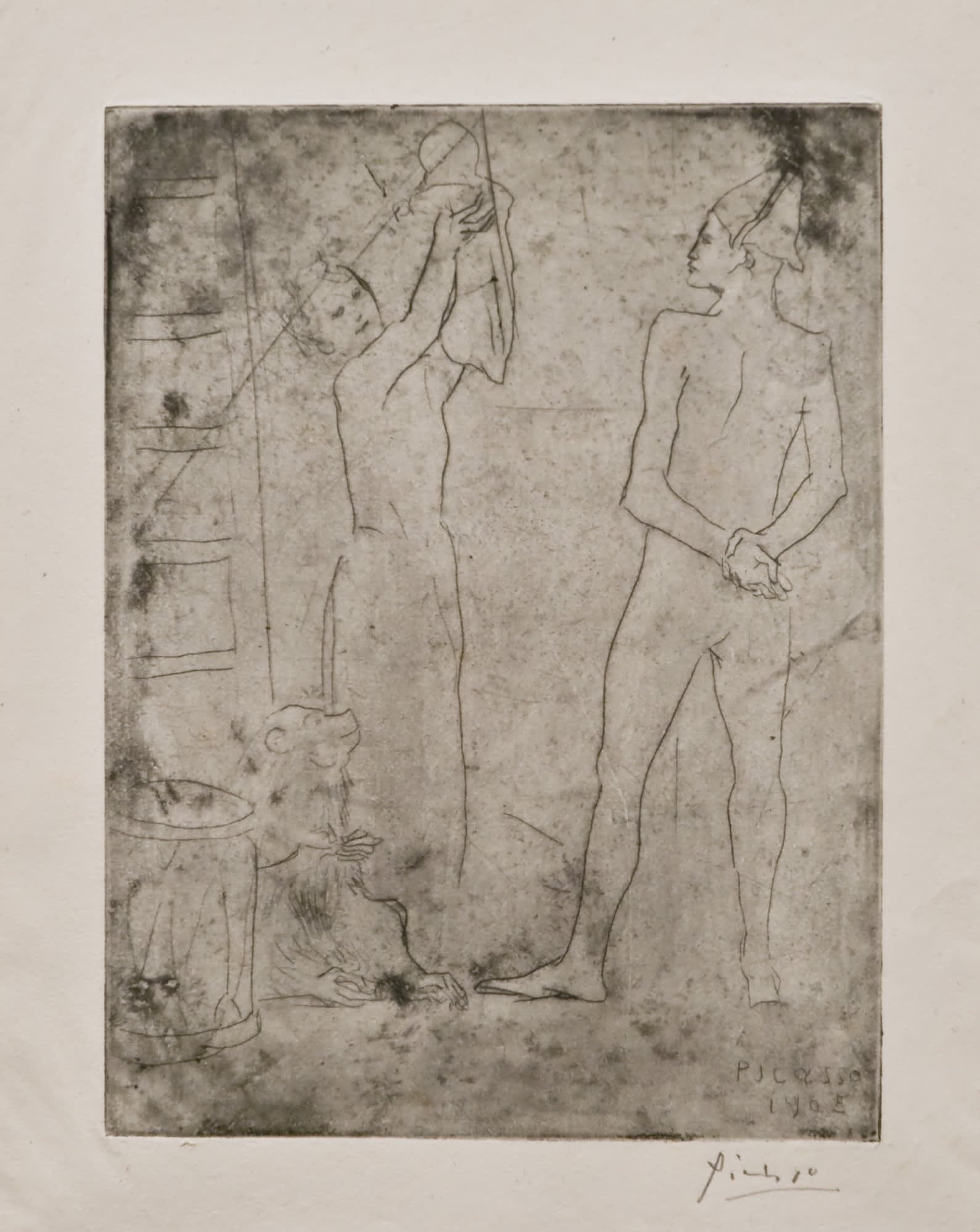

La Famille de Saltimbanques au Macaque (Bloch 11), 1905, drypoint, 9 3/8 x 11 3/8 inches

Picasso collaborated with the Parisian master printer Delâtre and continued working on the Saltimbanque Suite through 1905, with the hope that they would be commercially successful. Le Repas frugal (B1), the first and largest in the set, was a major undertaking for him. Though copper is harder, better metal for making etchings, Picasso used a zinc plate, as he could not afford a copper plate. He scraped down the zinc plate that had previously been used for a landscape by his friend, the Spanish artist Joan González. Some slight ghost image still shows through on the upper right side of the image, where the scraping was not complete.

As he went through dramatic transitions in both his personal and artistic life, Picasso captured the atmosphere of his environment while commanding the technique with his delicate, elegant lines. Utilizing printmaking, he was able to reflect a whole lifestyle.

Picasso’s attempt to make money off the work proved largely unsuccessful. He wound up giving many away to friends and fellow artists and the prints went largely unnoticed. That is, until about six years later when art dealer Ambroise Vollard saw them. Enamored with the Saltimbanques series, Vollard bought the fifteen plates to publish them. First, he had them steel-faced**— a process in which they're coated with a thin layer of steel to prevent them from wearing out. Then he printed editions of 27 or 29 on Japon paper. Following with an edition of 250 impressions of each image on Van Gelder paper. It was a large number; a testament to how much Vollard believed in Picasso’s abilities.

Picasso and Vollard continued working together until the death of Vollard in 1939.