In past weeks we’ve talked about Marie-Thérèse— Picasso’s young and submissive muse, we’ve talked about art dealer Ambroise Vollard’s suite of prints, and we’ve talked about Picasso’s recurring use of the Minotaur motif including the blind Minotaur.

This week, we look at an etching that swirls together all the above. Picasso created the MINOTAURE AVEUGLE GUIDÉ PAR MARIE-THÉRÈSE AU PIGEON DANS UNE NUIT ÉTOILÉE (B225) (S.V. 97) in the fall of 1934; the 97th of the 100 etchings from the Vollard Suite.

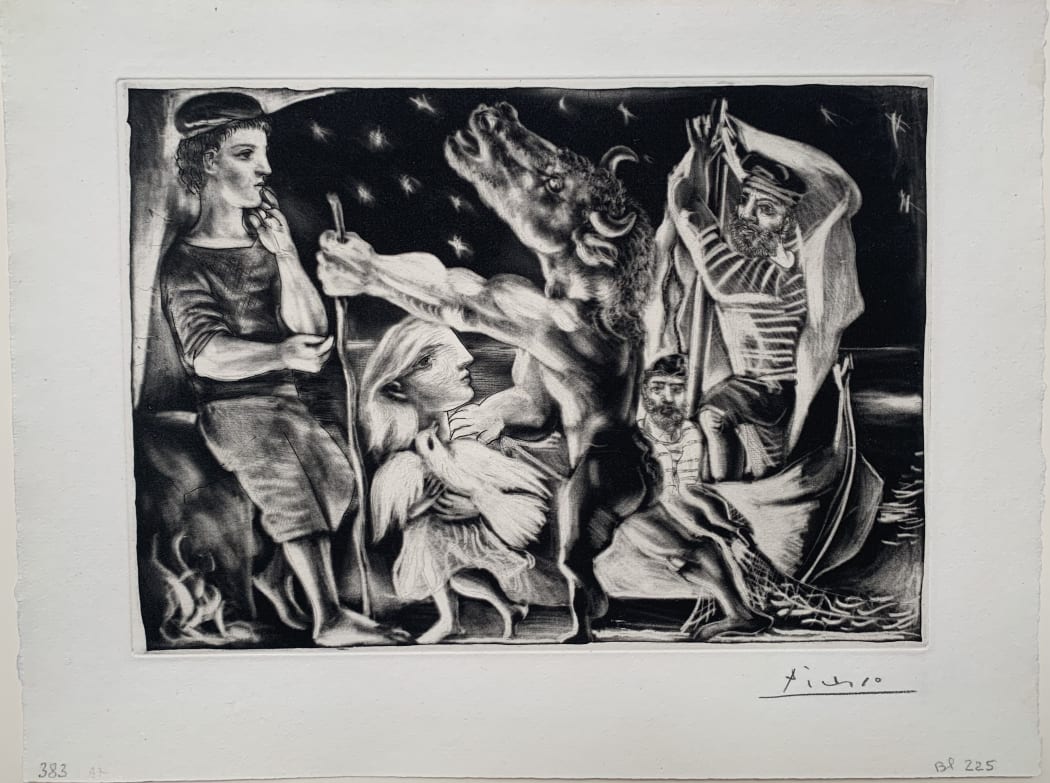

Of course there are many things going on in this image, but for now let’s focus on the aspects of it that we’ve touched on in the past and how they differ in this version. We see a starry night sky above, the sea in the foreground, and the blind Minotaur. He places his arm on the shoulder of Marie-Thérèse— she is again represented by a small girl with a dove in her arms— as she gingerly guides the stumbling half-man-half-bull forward. We also see his vessel and sailor fmen behind the blind Minotaur. Is he being led away from them? When looking at this image, it’s also hard not to think about the expression “follow something blindly”, as it depicted literally here. And what is the meaning of the Dove? Its wings are spread, clutched close to Marie-Thérèse’s body. Could it signify a peaceful messenger she is carrying to deliver important news?*

We instantly recognize that the Minotaur is Picasso, as we’ve seen him consistently identify the Greek mythological creature as his own alter-ego. A personification of man caving to his animalistic desires? Or more succinctly put: the beast within. But the minotaur depicted here is not the one in control. As large and ferocious as he is in size, he does not hold the power. Instead, he is vulnerable, reliant on the beautiful little girl. Marie-Thérèse perhaps best summed up the dynamic between herself and Picasso. She once said, “I always cried with Picasso. I bowed my head in front of him.”** So why the seeming shift portrayed in this image?

To understand, we need a quick recap and catch-up on the status of Picasso and Marie-Thérèse’s relationship: Marie-Thérèse was just 17 years old when Picasso first met her in 1927— the start of a seven-year-long secret, taboo affair. Olga, still married to Picasso, knew about Marie-Thérèse, but kept quiet. At the time of the etching, Marie-Thérèse had just recently told Picasso that she was pregnant with his child. Further adding complexity to the situation. Though he didn’t want to fully end things with Marie-Thérèse, he had begun to spend time with Dora Maar. And Marie-Thérèse’s pregnancy made the situation all the more knotty for Picasso. Not to mention, in learning of the pregnancy, Olga left Picasso, taking their son with her. Essentially, it was a real-life soap opera.

Picasso poured his mixed emotions during this time into the work. His anguish, his confusion, and, perhaps above all, his longing to not have the status quo of his life disrupted. Even the darkness of the etching mirrors Picasso’s inner turmoil.

This wasn’t the end for Picasso and Marie-Thérèse. But, just as we are soon approaching fall and leaving summer behind, Picasso was turning the page on the most taboo and passionate chapter of his life. A new muse, and, as potentially foreshadowed in Minotaur Led by a Little Girl in the Night, larger political themes were on the horizon. But more on that later.