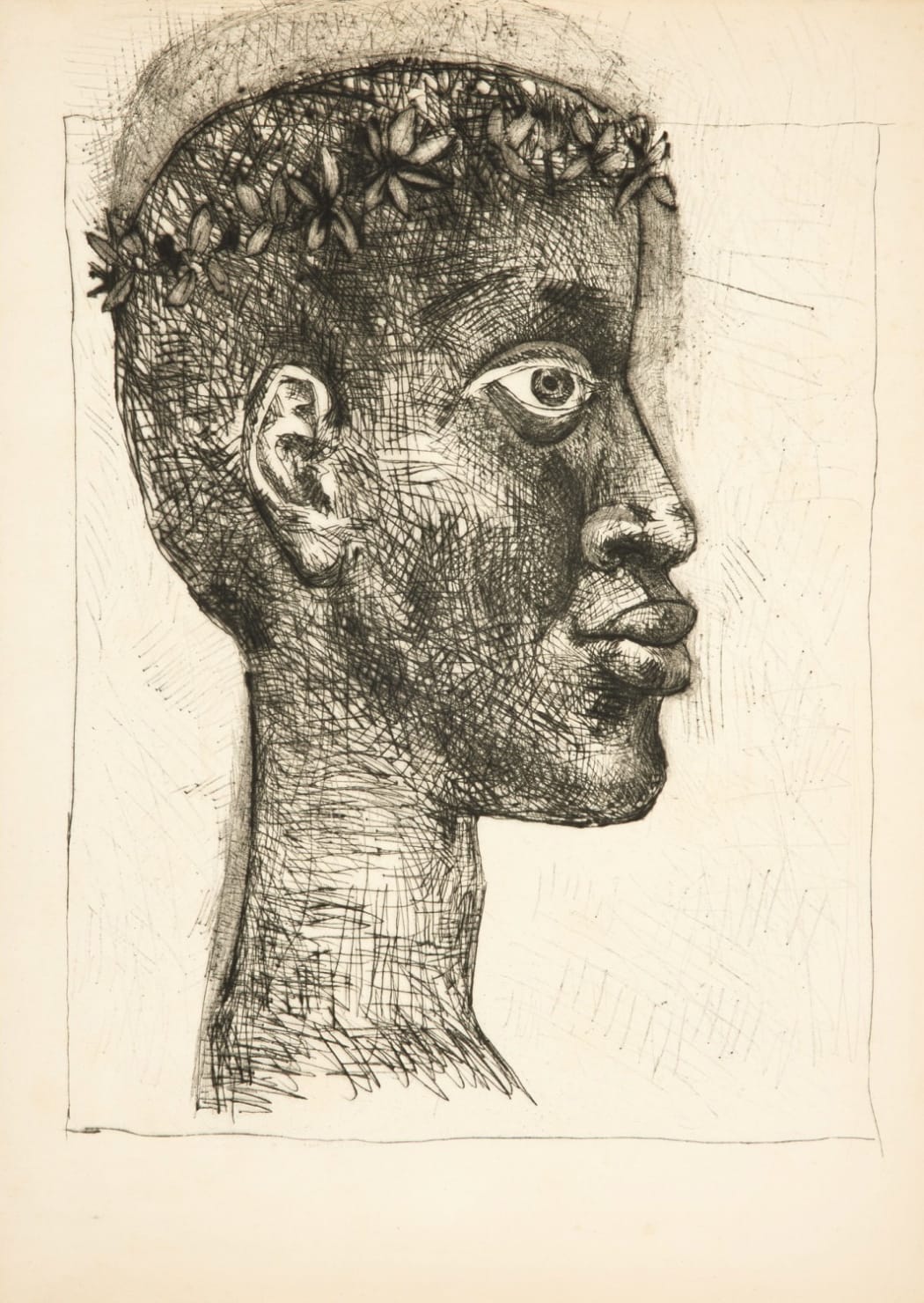

How many of these weekly notes have been about Picasso and a picture of a woman? I assure you, it is not bias on my part; it’s proportional to his oeuvre. Images of women vastly outweigh those of men. While I can’t give you an exact figure today, I’m sure that a good handful of the images that do feature men are, in some way, self-referential (see the unlikely bearded artist and the Minotaur). Of course, there are the exceptions. Exceptional exceptions, like the drypoint portrait pictured above: Négre (B633), whose plate was created in 1949 as the cover work for a collaboration between Picasso and the politician, poet, and intellectual Aimé Césaire.

It is Césaire’s profile figured in the print. Césaire was raised on the Caribbean island of Martinique, a colony-turned-territory of France. He traveled mainland on an education scholarship and in the 1940s, during the war, became intertwined with the surrealist movement by way of a newly formed friendship with the French poet and famous writer of the Surrealist Manifesto, André Breton. (You’ll remember that it was Picasso’s dear friend the poet Guillaume Appolinaire created the term “sur-real” to describe Picasso’s set design for the ballet Parade in 1917 – read more about that here.) Surrealism was useful to Césaire in his co-formation of a different movement, Négritude, which sought to cultivate collective Black consciousness and foster a sense of shared heritage across the African diaspora. It was expressly anti-colonialism. Stylistically, writers in the Négritude movement drew on the method developed by Breton and his peers, employing surrealism to explore the diasporic self; thematically, the writing pondered identity, belonging, home-going.* This is exemplified in Césaire’s most well-known and highly influential work, Cahier d'un retour au pays natal (or, Notebook of a Return to My Native Land), which was published fragmentarily throughout the decade, and finally published as a whole in 1947.

So how did these two great figures of the literary and visual art world collide? The question should actually be – where? In 1948, the Communist Party held the World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace, in Soviet-controlled Wroclaw, Poland. You can read more about Picasso’s cultural experience of the event here; I can summarize it pretty quickly by saying that though Picasso had become a member of the French Communist Party in response to the war, he was more opinionated than he was political. Césaire, on the other hand, had been elected mayor of Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique, and deputy to the French National Assembly for Martinique just a few years before (he would serve on the French National Assembly for almost five decades). For Césaire, politics and art and self were entangled concepts – as John Berger wrote, “The fact that Césaire [was] a French Deputy is almost as important as his being a poet; the artist needs the clamour and hopes of those whom he represents.”** Of course I am tongue-in-cheek when I say, who knows what Césaire could have possibly seen in Picasso? But following the Congress, the two artists collaborated on a poetry collection, Césaire the author and Picasso providing the graphic work for illustration. It was published in 1950, and the cover image was the one pictured above – Négre (B633). A picture of Césaire, adorned with a crown. They called it Corps perdu, “Lost Body.” I’d like to share a few of my favorite lines of the titular poem, with no intent other than appreciation:

Outside in lieu of atmosphere there'd be a beautiful haze no dirt in it

each drop of water forming a sun there

whose name the same for all things

would be DELICIOUS TOTAL ENCOUNTER***

Delicious total encounter. Perhaps a new name to consider for our weekly reading series? Thank you for joining me on yet another journey through art, and looking forward to where we are taken next week. Until then, wishing you a safe and restful weekend.