Last week we asked the question: Why Munch and Picasso? I answered by way of one of Edvard Munch’s most notable images: The Sick Child, whose creation is so important in the artist’s life that knowing that artwork well is like knowing a piece of Munch – not Munch the man, but some piece of his soul. And while there’s still more to say on The Sick Child, and indeed more to come, I’m flipping the coin this week. My other attraction to these artists is within their instances of utter technical singularity – the way their use of the commonplace tools of printmaking have surprised me; me, who has studied these artworks for roughly five decades, and who knows their gestures like a third language.

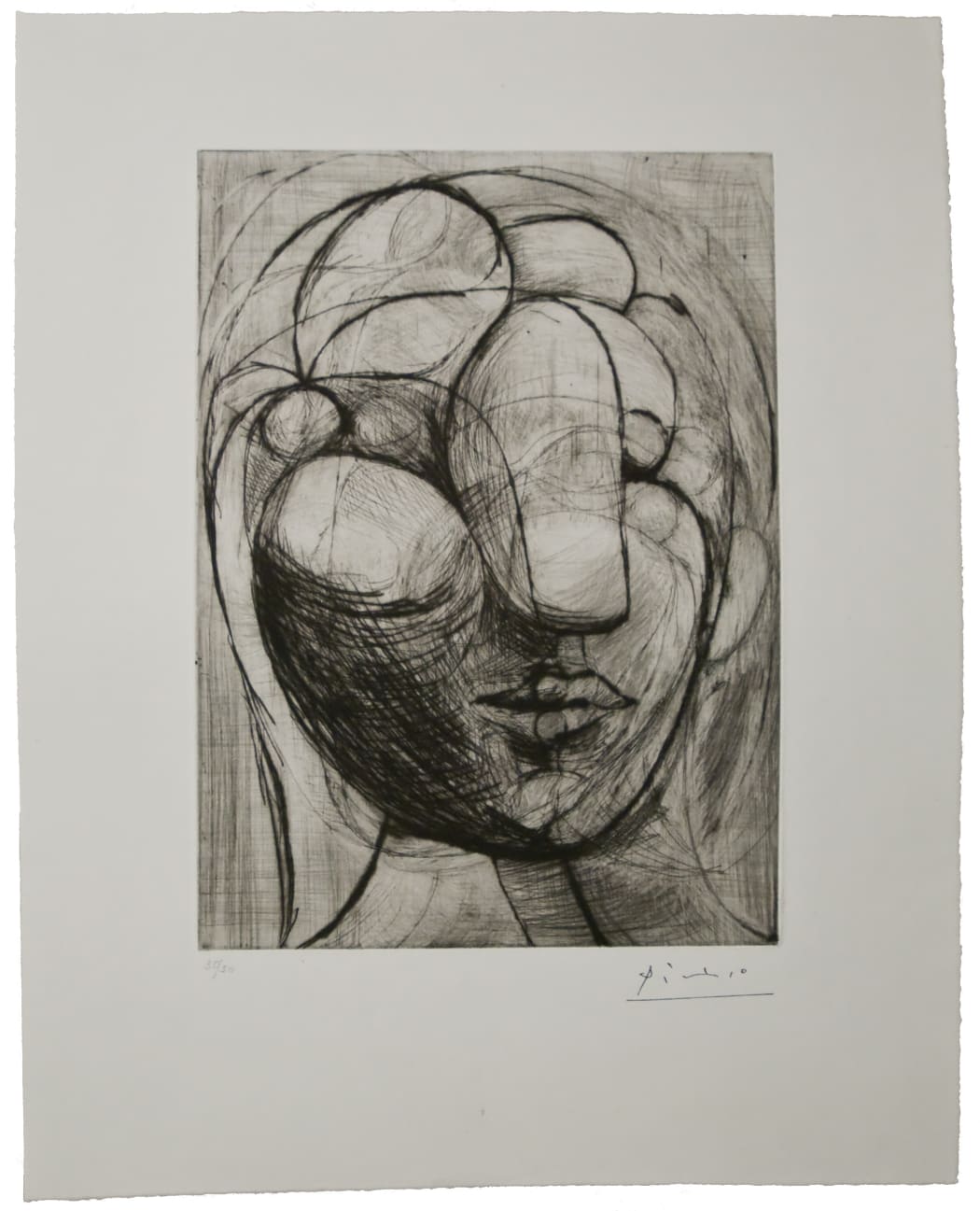

My favorite case, one that I have hanging in my own home, is from Picasso: Sculpture. Tête de Marie-Thérèse (B250), created in 1933. When we think of Picasso, 1930s, surely we must be thinking about two things: first off, the Suite Vollard, one his largest, most exploratory collections (read much more in depth about it here and, as a highly relevant example of one of the smaller series I’ve referenced, here). It was really a collection of smaller series, the first created in 1930 and the final series capstoning in 1937 – his three (plus one unpublished, making four) portraits of Vollard himself. As with the majority of his pre-War graphic work, the Suite Vollard was made up of etchings and drypoints, with some dabbling in aquatint as the series went on. B250 was not part of the Suite, but was created in conjunction – and though it stands apart from those images, it does bear a face familiar to those familiar with the Suite: Marie-Thérèse Walter.

What makes it so distinctly its own work comes down to technique. Picasso worked directly on the copper plate with a sharp-pointed needle. With the removal of intermediate steps and media, the effect is much like that of a drawing: immediate, forceful, intimate. It gives us the feeling that Picasso moved from inspiration to plate in one swift movement; that the notion that delivered this image struck him suddenly, perfectly. This is not to say that he did not struggle with the composition – an image that might have ordinarily required a day’s work (if the pace of the Suite Vollard is any indication) instead went through twenty states, which is like saying twenty major iterations. It began with Marie-Thérèse’s profile looking off the page to the right, then to the left. Subsequent states brought her gaze straight out of the page, the initial formations swallowed up by the sequence of shapes that define her cheekbones, eyes, and forehead. Picasso left the ghost of a pair of eyes displaced just to the right of her formalized ones. The effect is that of dimensionality, depth – more an image of a bust than a figurative head.

I said that 1930s Picasso signifies two things and we’ve discussed one. The other is the advent of a new phase: sculpture. Not long before this print was made, Picasso had purchased a country retreat: the Château de Boisgeloup in Normandy, forty miles outside of Paris. Tucked away across the grassy grounds from the sprawling light-stoned home was a stable. Picasso converted the stable into a studio, thus separating his work space from his home life – or, you could say, separating his golden mistress, Marie-Thérèse, fom Olga, his tumultuous wife. In a much more expansive, much more isolated space, Picasso found the room he needed to experiment with sculpture. Of course, as alluded, Marie-Thérèse often joined him in the Boisgeloup studio; the sculptural pieces that left it less than discreetly bore her stately Roman nose. So it is not coincidental that in B250, Marie-Thérèse’s head appears to be in the middle of a sculptural transfiguration – her features seem at once solid, carved, fixed, as they do in rapid movement. They rise from the page; we know it is flat, and yet our eye cannot believe it is not three-dimensional. And so it is not just the masterful drypoint technique that makes this image feel so alive; it’s also the aspects of sculptural technique that have made their way into the mix, a transparent yet evocative fusion of ideas that indicate the massive artist progress that Picasso had achieved – and hardly midway through his career.

I hope you’ve enjoyed my homage to Picasso’s homage to sculpture – it is one of my favorite prints, and it is always a joy to share a favorite work with friends. Until next time, wishing you a safe and restful weekend.