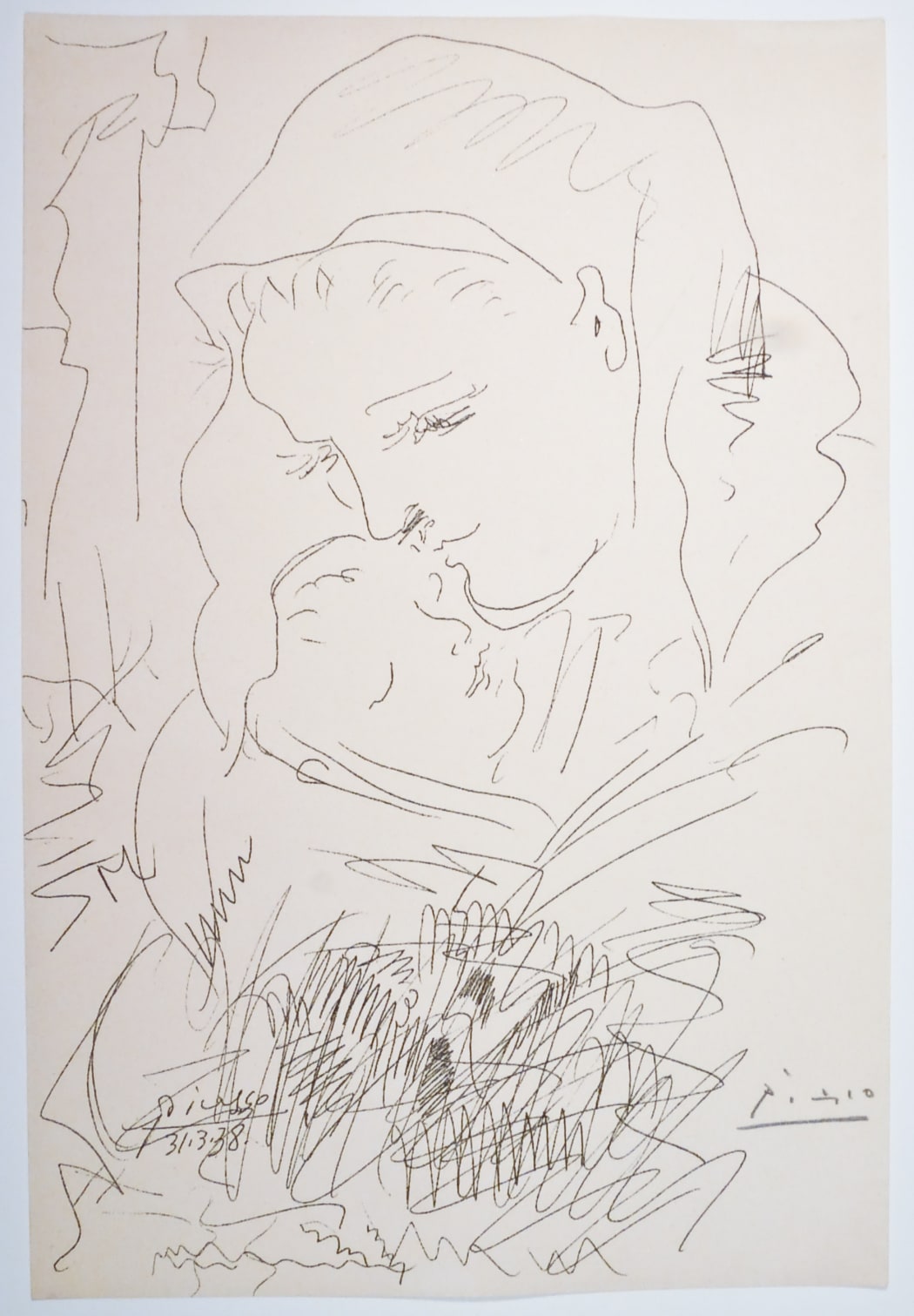

I hope that you are out walking between budding trees, and as swollen as they are with perhaps uncomfortable degrees of pollen, enjoying gentler days. The past twelve-plus months have been ones in dire need of renewal; the lightening sense of spring has never been so relieving. And yet – it all feels rather traditional, familiar. Picasso seems to have sniffed it himself, back in March of 1938. The image that crowns these lines is born of spring air. It is Maternité (B1829), motherhood: the image of creation.

Double-meaning intended here – Picasso rendered variations of this image again and again throughout his career. The fascination first budded in his youth, in his Blue and Rose Periods, a time in which it is storied that he conceived and lost a baby with his then-mistress, the artist’s model Madeleine (click here to see her profile). Works exploring an adoring mother and her new baby or young child proliferate all of his many styles and techniques – there’s a turn-of-the-century neoclassical painting of a Madeleine-faced mother, a 1930 colored aquatint adapted from a cool-toned Blue period painting, a 1963 lithograph of a laurel-crowned mother set against a green grassy field. Though he worked the motif repeatedly, there are only a few impressions of this version, B1829, known. It was created from an undated drawing, signed by Picasso in the lower right-hand side of the image. After reworking certain aspects of the drawing (hence the scrubbing in the bottom center), it was printed and he signed it again, this time in the lower left-hand side, and with a date.*

If you have been reading with me throughout the year, you’ll have gleaned two things: the foremost, Picasso’s prints were the pages of his diary. It is within them that we can glimpse the artist’s psyche, the thoughts his imagination churned into images so rapidly that they needed to be sketched, released, into works he was able to complete in a day, and revisit later. It is no coincidence that motherhood, in its literal and figurative forms, is a subject frequent to his prints. Which brings me to the second — in his own complicated way, Picasso was a family man; he was fixated on the love in his life. He had four children with three different women throughout the course of twenty-eight years: Paulo, Maya, Claude, and Paloma. B1829 is not in the likeness of a single one of his children — but it is about all of them, his imagination of them before they were born and after. I would not go so far as to say that Picasso was a faultless father, by any means; what is clear, however, is that he had a lifelong appreciation for the springtime adoration of a new parent.

Wishing a most happy Mother’s Day to the all-important women in your life: the moms, grandmothers, sisters, aunts, friends, mentors, and lovers.

A correction from last week’s mailing: one of our astute readers has pointed out to us that Picasso’s son with Olga, Paulo, did attend his private burial at Vauvenargues. Our apologies for the error, and thanks to our close-reading recipients.