At the time of last week’s goodbye, Picasso had met Jacqueline Roque – and had loved her from the first. Today we catch back up with the pair in 1955: Picasso’s relationship with Francoise Gilot was squarely closed; Olga Khokhlova, his legal partner since their marriage in 1918, had recently passed, leaving Picasso “single” for the first time in 37 years; and he’d bought the villa La Californie, overlooking the blue Bay of Cannes. There, Picasso and Jacqueline installed themselves until their marriage, in 1961.

Picasso created Jacqueline de profil a droite (B854) a few years prior to that. The motifs of Jacqueline’s profile are instantly recognizable; her big, almond-shaped eyes, wealth of thick dark hair, straight nose, arched brow. Her gaze is gentle, downcast, and her lips are softy set. But in contrast, the shading around her eyes is dark, dramatic, reflecting the intensity of her dress, hair, and the background. The tension, the ambiguity of the lithograph raises a question, one that would long linger in the hearts of Picasso’s friends, family, and admirers: how exactly do we remember Jacqueline Roque?

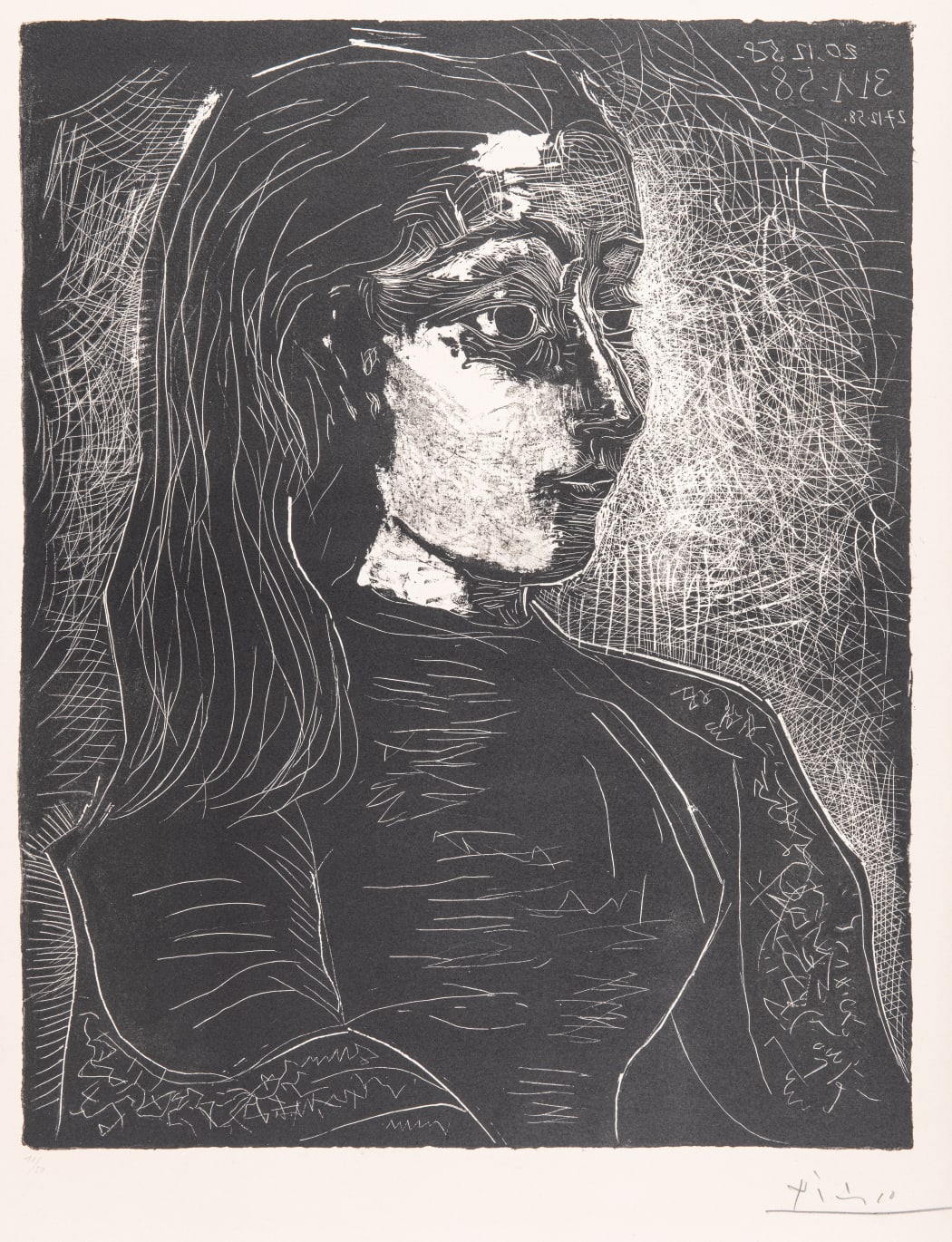

Jacqueline au Mouchoir noir (Bloch 874), 1959, lithograph, 25 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches

There was a reason the biographer Antonina Vallentin nicknamed Jacqueline the “Sphinx Moderne,” and it was not just because of her feline features, as are so accentuated in the 1959 lithograph Jacqueline au Mouchoir noir (B874). In some versions of B874, a shadow falls across half of Jacqueline’s face; a coincidental quirk in printing, maybe – or maybe there is a kind of Jungian unconscious at play in the print. For Jacqueline did not always wear that soft smile, that enduring gaze; she was notably jealous against “intruders,” before her time otherwise known as visitors. During their stead at La Californie, she often shut the door to photographers, journalists – even some friends. Fast forward to April of 1973, to the time of Picasso’s passing, she shut the door again – this time, unforgivably, to family. She barred Francoise and Picasso’s children, Paloma and Claude, and Paulo, his son by Olga, from attending their father’s funeral.

Despite these blights, in most memories Jacqueline is recalled as attentive and charming and domestic. She was devoted to Picasso’s needs and wishes; a great cook, a careful caretaker, and a loving friend to the artist’s cherished Afghan greyhound, Kaboul. She learned an eye from Picasso, taking up an interest in photography. She enjoyed listening to music, reading, and playing with her young daughter, Catherine. Unlike her predecessors, Jacqueline from the first accepted that Picasso was devoted to his art, that it was his life; she loved him as he loved it. And it does seem that Picasso found peace in her presence, a calm he had lacked since his 1930s relationship with Marie-Therese, and an intellectual compatibility similar to that he had enjoyed with Dora and Francoise, but this time without the competitive tension.* Despite his years, the Époque Jacqueline was one of his most energetic periods of artmaking. He created over 400 portraits of her, far more than any of his other loves. Of these works, the Guggenheim Museum curator and Picasso scholar Carmen Giménez says, “[They] are so free and full of love… Jacqueline created peace for him.”**

Peace Picasso may have felt, finally, within the partner with whom he’d live out the rest of his years, but the prints included in this Époque encompass more than just warm renderings of his wife. In the coming weeks, we’ll look more closely at the series of prints and major shifts of style that colored Picasso’s final twenty years – in some of these, peace is far from Picasso’s heart.