Last week, when we left off with Picasso’s 1953* lithograph L'Italienne (B740), we’d recognized a profile in the background – thick dark hair pinned back, an elongated neck, a straight and sturdy nose. Though at the time of creation, it wasn’t likely that Picasso’s contemporaries would have known her exact identity, her features rang with familiarity – maybe they’d seen her in something at the Louvre? Given Picasso’s tendency to draw often very direct inspiration from ancient artworks as well as those more recent and of large cultural significance, some of his peers thought it possible that she’d been adapted from one of the women featured in Eugène Delacroix’s Femmes d'Alger dans leur appartement ?* In the 1834 painting, three women share a dimly lit space, implied to be a harem. The profile in question does appear awfully similar to one woman’s, distinguished by holding a water pipe, her long hair brushed over one shoulder and held in place with a flower.

Even more than Delacroix’s lady, she appears with striking similarity to a subject who had appeared in a series of Picasso’s oil paintings in 1954, the year before. Picasso, in the midst of ending things with Francoise Gilot, chose to name those paintings and that subject Madame Z, potentially to protect the identity belonging to this new subject. Madame Z was a study of the carriage of his model’s head; she had an enlarged neck and geometrized hair, an imposing sense of charm, of dignity. Antonina Vallentin, one of Picasso’s biographers, characterized this subject: Un sphinx moderne.* *

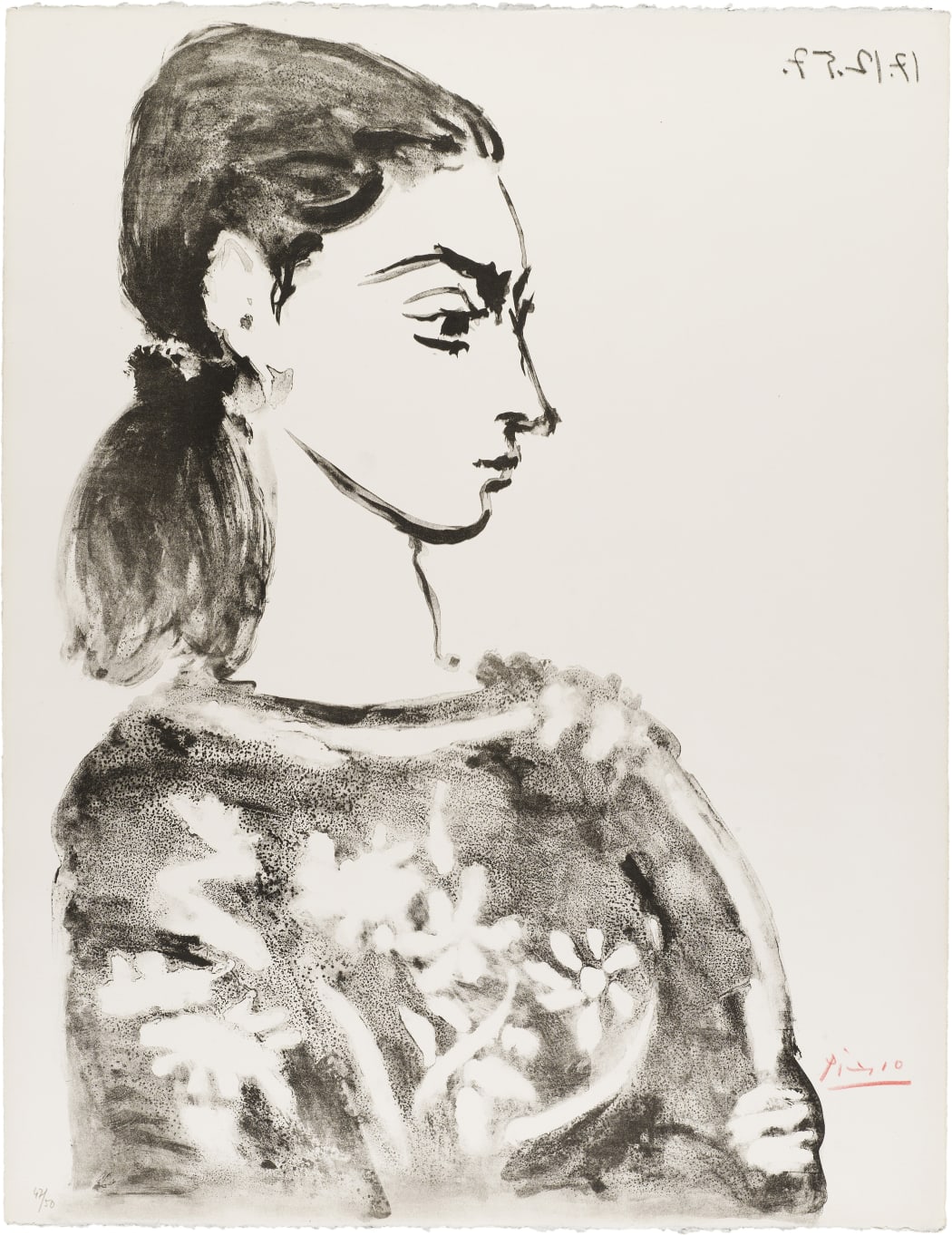

By now, you’ll have made the connection between these three profiles, and the one that sits aboves these lines. In Femme au corsage a fleurs (B846), an austere woman with an arched brow and distinctive jawline purses her lips and focuses off the page. She is Jacqueline Roque, Picasso’s final muse and, though usually not as romanticized as his earlier loves, his most decorated. Jacqueline appears in more Picasso paintings and prints than any other single woman.

The pair met in the Madoura pottery studio in Vallauris, in 1952. He was there making ceramics, an artistic turn that would become a surprising passion in his later years; she was a salesgirl. Picasso was 72 years old, she 27; he was still involved with Francoise, she a divorcee and single mother. The courtship was subtle, unexpected, drawn-out. One morning, she woke up to find a beautiful white dove chalked against the side of her house; in the evenings, upon returning home from the studio, she’d find a single red rose on her doorstep, awaiting.*** During this sapling stage of their romance, Picasso frequently left Vallauris on trips to Paris and elsewhere; he was distracted by the eventual and painful break-up with Francoise; he was always dedicated foremost to his art. And though Picasso was not always present, Jacqueline was far-sighted, certain of their connection; when other women vied for the position that Francoise had vacated, she was undeterred. For a brief period in this in-between time, she left France and traveled to Africa. A photograph taken in December 1953 shows her return to Vallauris, to the Madoura studio. In it, Picasso is lighting her cigarette. It is the first (photographic) image of the two of them together; months later would come Madame Z; after that, L'Italienne; and not longer after that — that profile would never again be misconstrued as an adaptation. She was to be wholly his, Picasso’s.

So begins L'Époque Jacqueline, the modern sphinx, the woman whom Picasso took a lifetime find. Next week, we’ll dive a bit deeper into the special relevance of Vallentin’s nickname, and visit the soon-to-be Picassos at home, at Villa La Californie.