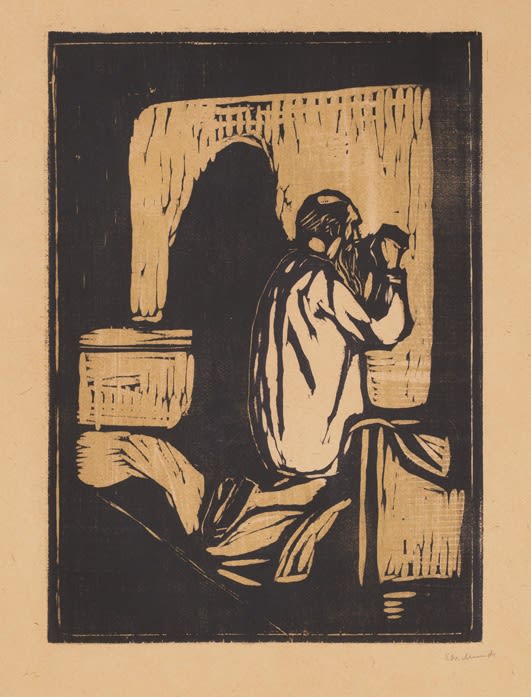

We left off last week with Picasso in Vallauris, but today I excitedly interrupt our vacation to the South of France. The gallery has recently acquired a work from a private collection that is too wonderful not to share immediately. The print is catalogued as Old Man Praying (W205), though some editions are hand-notated with the title “The Praying Man” (done either by Munch, or by his printer). It was created in 1895 – Munch’s most prolific printmaking period, the same one in which he completed lithographs like The Scream (1893) and Madonna (1895), and woodcuts like Angst (1896) and Melancholy (1896). The subject matter of Old Man Praying is, perhaps, the most biographically pertinent one to Munch’s foundation as an artist: the strife of his childhood, the constriction of his religion, and the shroud of his family – all of these elements are wrapped up in his father.

When Munch was hardly five years old, he lost his mother to tuberculosis; about ten years later, his sister Sophie passed the same way, at just fifteen years old. These early losses made a vivid impression in the young Munch’s psyche; they impacted his father, the head of the household, in a different way. Christian Munch was a military doctor, considered deeply religious even in their conservative Norweigan setting.* He was a traditional man, accustomed to old-fashioned designations of husband and wife – he to work, she to take care of domestic matters. The loss of his wife devastated Christian; he struggled emotionally as well as logistically, with matters he hadn’t had to consider before – a cross to bear on his children. Rather than turning inward, knitting his remaining family closer together, he turned outward, to God. He believed that if he really prayed, if he was true and pious in his faith, things would get better.

Needless to say, there was a great distance between Christian and Edvard – a gap of personal and ideological difference – and by the time Edvard reached adulthood, it was unmendable. The angsty young man took to rebellious efforts, joining the “Kristiania Bohème” in their late night escapades. This group’s “sex, drugs, and rock n’roll” was more like subverting gender role expectations, drinking, and talking about art – by today’s standards, perhaps not the worst group for your kid to fall into. But this was not Christian Munch’s view. Edvard was not going the direction Christian had anticipated; he seemed aimless, faithless, morose. Without hope once again, he turned to God and prayed.

You can imagine the scene that inspired the print: Munch comes home late one night (or, early one morning), after a smokey night at the bar. He steps into the quiet, sleeping house. As he passes through hallways, snaking his way to his bedroom in the dark, a sliver of light presses its way out of a crack in a doorway. Munch cannot resist – he peers into his father’s room, the room awash and shadowed in the dying yellow-black light of a candle. Christian Munch kneels on a pillow, his face to the curtained window, and holds his entwined fingers tightly to his forehead. An inky black shadow pools behind him. He is whispering under his breath, his face hardened with grief, with desperation. Edvard knows, in his heart, that he is the cause of such pain; and yet he cannot change who he is, who he is becoming, for his father’s faith. This scene may be fiction, but the emotion is true to the print.

What Edvard Munch saw that night moved him, and the artwork he created carries the impression of that emotion even as it enters its new home, in our collection. This particular sense of personalness, of intimacy, was revolutionary for woodcut prints in Munch’s time. Long before the age of metal plates, wood blocks were used to create prints that were decorative, or that served as a record of events. They fell out of popular use with the advent of new technology that rendered more precise, detailed images. At the end of the 19th Century, Munch and his contemporaries in a sense rediscovered the technique, marrying it with very striking, very personal imagery. In particular, Munch’s works demonstrated the woodcut’s subtle emotional capacity and revealed its unlikely compatibility with the dark revelations of the modern age. This is exemplified in his encompassing influence on the German Expressionists, whose imagery holds the echoes of Munch’s tortured figures and landscapes, and who carried on the legacy of the woodcut technique for decades after Munch’s death.

My thanks for indulging that little detour. Next week, we’ll be back to our regular programming. Until then, a safe and restful weekend to all of you.