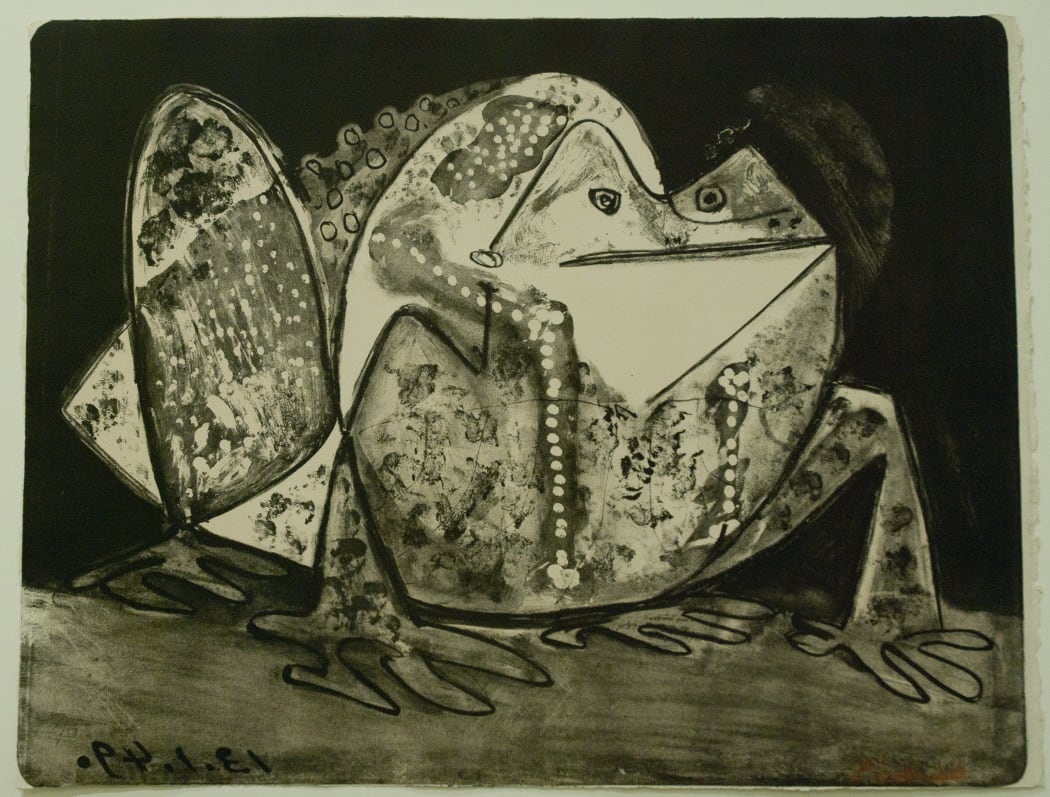

I have to make the distinction that we are returning to lithography this week, because Picasso loved animals and turned to the subject in other media (most famously aquatint, which you can read more about here). The stoic toad that perches monumentally above these lines (B585) was created along with a series of same-sized animal-focused prints in January of 1949 amidst a flurry of lithographic production, more typically featuring human figures and faces (you can read more about that here and here). Among those works, our toad is a special case, an experiment gone right. Done on a zinc plate rather than the more typical stone, he has an unusual presence: though flat, as though he were embedded into the paper, his skin is textured and burnished, giving the illusion of effervescence and hinting at his aquatic nature. He is just as much a part of the natural world as he is other-wordly. And he is just as other-wordly as he is of Picasso’s world. Post-War Paris was healing, and Europe was rife with socio-political tension. Ostensibly, Picasso turned to a more innocent, more playful subject.

While he stands out from Picasso’s oeuvre of lithographs, the toad also tells the story of his approach to the medium. Art critic Erich Franz called the style a “mutability of means:” in Picasso’s lithographs the surfaces of form and ground are interlinked; lines are softer, blurring their “function as boundaries” between the subject and the world it lives in, “integrating a face or a figure into the visual presence of the picture.”* Which is to say, our distinction between the figure represented and the page itself is confounded. In the lithographs of Francoise, the print seems to intelligently meet our gaze; and in that of the toad, his small, somber face appears uncannily, and sternly, human. It is as though Picasso is joking with us about our roles as viewers of art – his toad, decidedly, is not.

La Colombe (Bloch 583), 1949, lithograph, 21 1/2 x 27 1/2 inches

The toad, the dove you see above (B583), and some four hundred other wonderful lithographs would not have been possible had Picasso not found a warm space to work at the Mourlot printing studio during the chilly, wet winter of 1945-46. He hadn’t touched the technique for years – and even then, his work with it had been exploratory. But at Atelier Mourlot, he was working with the best. The family business had evolved from printing wallpaper, to books and posters, to, by the 1920s, specializing in lithography and working with masters of mid-century art: Miro, Matisse, Chagall.** The studio was equally impressed with Picasso’s prodigious talent for grasping new forms of graphic art, calling his urgency, his drive to mastery, “merciless.” He worked the poor stone from eight in the morning to eight in the evening. During that time, the studio workmen would prepare a stone, Picasso would create the image, they’d pull a number of impressions, and immediately, he would be ready to embark on a second state. And on and on. Between each state, the lithographers would need to retouch the stone. Usually, all that treatment would alter the original design, more or less rendering it indecipherable – but, the studio says, there was a potency to Picasso’s work. “Each time [he made another state] it turned out well.” The process became part of the resultant image – as our toad shows. Through compulsive trial and error (multiplied by innumerable states) he forged a distinct lithographic style. “There was no stopping him,” the studio remembers. When they told him that lithographers usually wear a mask over their mouths when printing to prevent saliva from splattering the stone, Picasso merely laughed. “The saliva makes a blank,” he said, “and we can make use of it.”***

In these words we’ve been gifted a new meaning to the old adage “worth his spit.” And with that, this menagerie’s gate is closed. Next week, when we meet again, I’ll continue to talk lithographs – returning once again to Picasso’s more typical subject of the period, Francoise Gilot. Until then, a safe and restful weekend to all of you.