In 1946, Picasso created eight lithographic images over the course of a day. Eight. That’s seven and a half more than what most artists would call a serious day’s work. What’s more, lithographs differ from other print techniques starting from the beginning, where the artist “draws” his image either directly or through a transfer process onto a large, heavy stone with a greasy crayon-like pencil. The process of finalizing the image is not quick, nor is it done on the fly – not quite an image sketched in the park. It’s no wonder that the subject of the prints is the same: a long-faced woman with pronounced eyelashes beaming from her round eyes like rays from the sun (B396). If you read along last week, you’ll know just who she is.

If you missed it, we’ll catch you up to speed: When Francoise Gilot met Picasso, the Germans occupied Paris. She was studying law to make her father happy and painting to make herself happy; she was an avid reader of literature, a bit socially unsure but well self-attuned; she was close with her painting tutor – a young man from Hungary, Jewish on his mother’s side – and knew, from early on, that her life was about making art. When her tutor was precautionarily sent back to Budapest, she figured it was the end of her artistic career. As he boarded the train, Francoise remembers him turning to her. “Don’t worry,” he said, “in three months time you may know Picasso.” The tutor was right, almost to the day. What he could not have figured - what no one would have figured - was that she would encounter Picasso romantically, rather than as a pupil.

The two entered each other’s lives abruptly, worlds apart, with mutual insatiability. Far later, in her memoir, Francoise wrote that at the onset of the relationship she “was beginning to live the beginning of life. One doesn’t necessarily live the beginning at the beginning.”* We might understand her literally – she was entering her mid-twenties; Picasso, his mid-sixties. If Francoise was experiencing her first real bloom, then Picasso had long been on the verge of his.

And if the beginning of the relationship was remarkable, perhaps a little scandalous, then what we see in those eight lithographs – created two years after the couple’s first public appearance and the same year Francoise would announce her first pregnancy – is a continuation of the story. Francoise does not appear as the same subject, eight different ways. She appears as the same subject, in eight different settings, different moods, different lights, with different memories behind her and hopes in front. It is as though Picasso recalled these scenes all in the day he made them, drawing them up out of his memory or, perhaps, looking forward to time not yet spent. They are a testament to commitment. Coincidentally (or, not-so-coincidentally) these prints also highlight a time of new experimentation for Picasso. In his earlier career, he’d worked very little with lithographs; after 1945, he was prolific. Discussing the particular appeal with his friend, the photographer Brassai, he said, “There would never be a finished picture.” He continued, as though making a direct reference to the Francoise prints, “They are all different states of the same picture, which, most of the time, disappear during the course of work.”**

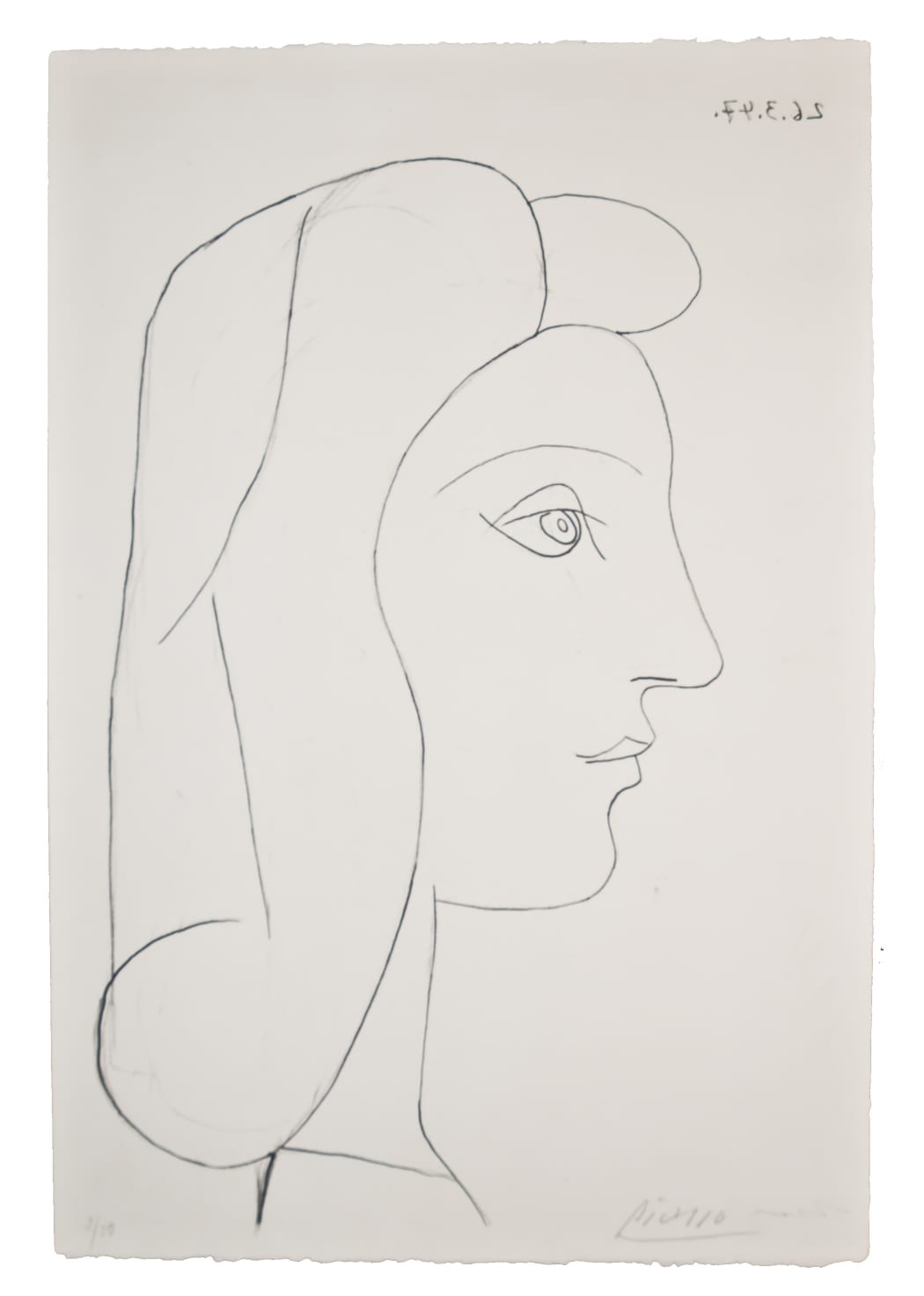

Though done a year later, Profil de femme (B436), pictured above, appears as though another state of the eight Francoise images. Lucky for us, in the print world, past states don’t have to disappear through the course of the work; we can see Francoise as Picasso did in 1946, and then again in 1947. She is still soft, warm, bright, balanced, but now Picasso asks her to turn her chin, and she appears in profile. The story continues again. Importantly, the relationship that seemed unlikely to progress from the “beginning” had developed; Picasso committed to Francoise in a way that he hadn’t since his marriage. As always, that real-life change corresponded to his art. For Picasso, Marie-Therese had been a muse for sculpture, a fresh figure and mutable profile for painting and print; Dora Maar had embodied something darker, the other side to life: pain and woe and wonder. Francoise would be considered differently by Picasso, and, subsequently, his audience would see her differently. This overarching image - whose “states” we’ve discussed so thoroughly this week - would change incrementally over the tour of the near-decade long relationship. Where it goes, we will have to save for next week.

* Gilot, Franoise. Lake, Carlton. Life with Picasso, McGraw-Hill (1964). (pp. 28, 44)

** Daix, Pierre. Picasso: Life and Art, HarperCollins (1987). (pp 283)

Comments

I really enjoy these pieces. I have no idea how I got on your list