|

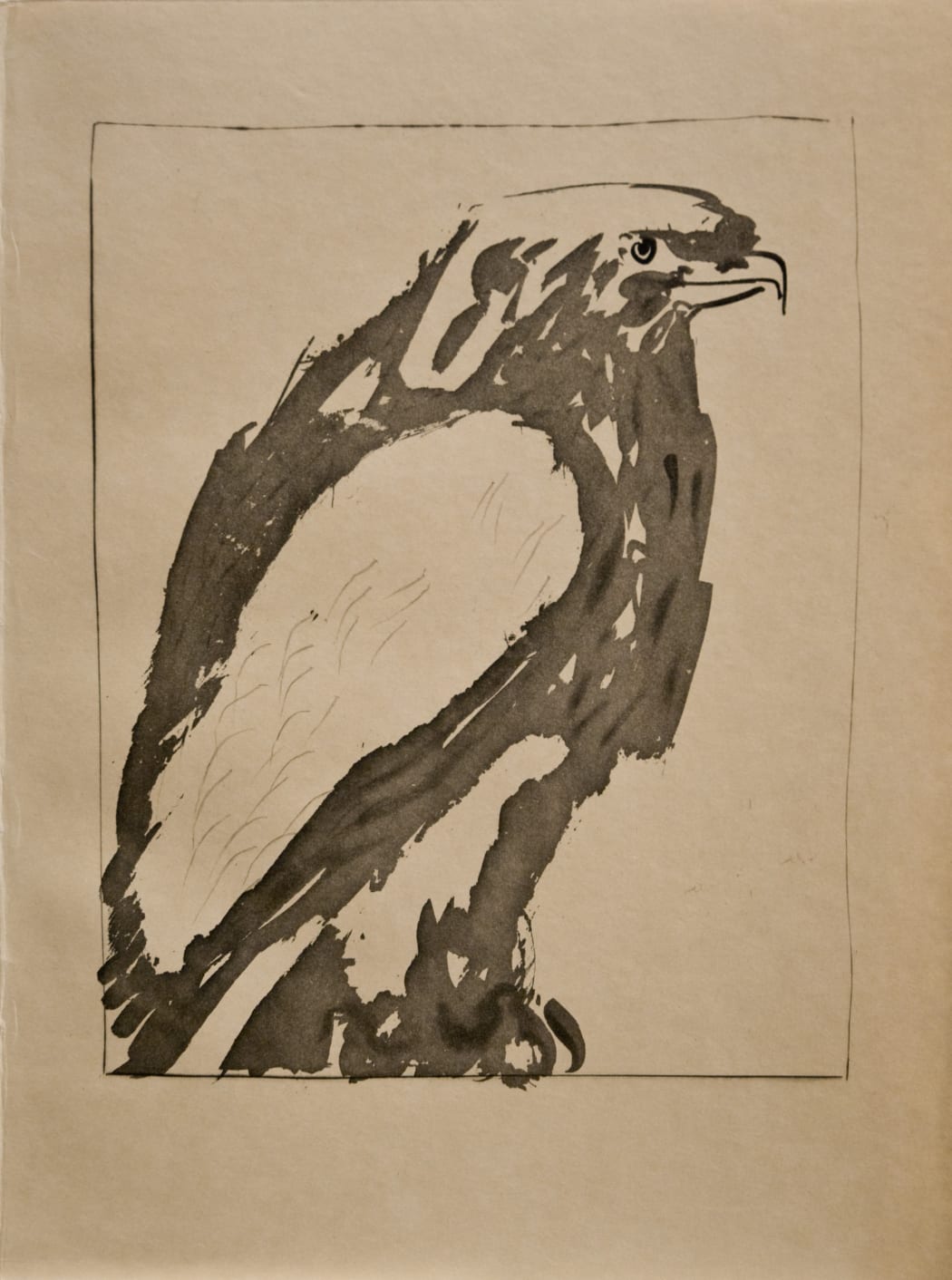

Ah, the eagle. We fly him this week in recognition of a major event for the United States – last week’s inauguration – but no doubt he was a symbol for freedom and courage long before this country chose him as its emblem. People have always looked to the natural world to better understand themselves, their values – us included. We’ve shown images like this before in commemoration of events – beautiful or whimsical or sweet aquatint animal prints, like the eagle’s twice-removed cousin, our Thanksgiving turkey – but we’ve never fully explained the story of Picasso’s creature series, simply called: Buffon.

The “Buffon” series got its name from Georges Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, an 18th Century French aristocrat-intellectual interested in calculus and the then-called “natural sciences,” who post-studies settled into a role as the keeper of the Jardin du Roi (which we now know as the Jardin des Plantes) in Paris. There, he got the idea to write the ambitious, controversial, first-proposed 50 volume text, Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière. How could a textbook on plants and animals be considered “controversial?” Well, 100 years before Darwin, in a time when the Church’s accepted doctrine was that man reigned biologically supreme and that the Earth could be no more than 6,000 years old, Buffon had a pot-stirring idea: that man and all other creatures were formed through and against some agent he called “organic particles.”

|