As the Suite Vollard so ably demonstrated, in the 1930s Picasso’s work was alive with imagination and tension – and, as always, women, whose real-life presence seemed to encapsulate those concepts for the romance-drawn artist. 1935-36 saw a turn in Picasso’s well-documented affections. Marie-Thérèse gave birth to a baby girl, Maya, and as family life once again took the focal point, an unexpected muse arose in the background.

It is hard to say when, exactly, Picasso began to see Dora Maar. It could have been one early fall evening, in Paris, when Picasso walked into the Cafe des Deaux Magots with a friend and saw over his shoulder, seated at the next table over, a young woman with dark hair, stark eyebrows, and pale blue eyes. She sat hunched in her seat with a pen-knife in one hand, her other palm splayed out onto the wooden table before her. Methodically and with unnerving speed, she brought the blade down between each of her fingers, moving from thumb to pinky and back again. Her concentration was so intense that Picasso felt nervous to break it, should he cause her to miss by millimeters in her game and puncture one of the black roses embroidered into her gloves. He did anyway, and art is glad he did. Later on, he would ask her for that set of gloves, to keep as a memento.*

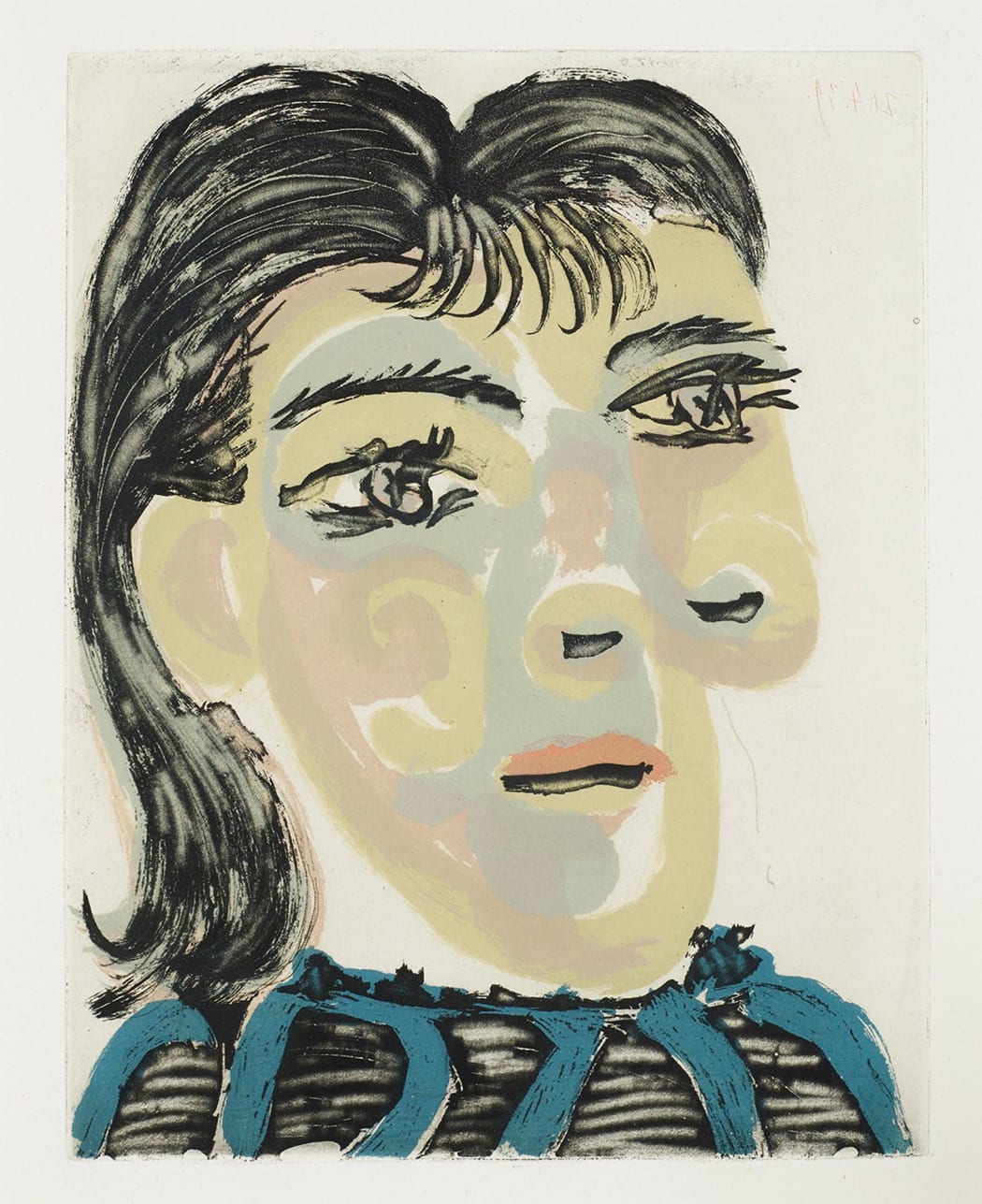

Of course, this first meeting may be more legendary in its fiction than in its facts. Which is to say that it does not matter so much whether this is a wholly accurate account of how Picasso and Dora met; this story carries a kernel of the truth of their relationship, a shadow of how Picasso saw her and therein how the world who did not know her by her own art would come to view her. The essence of this character is visible in the rare colored aquatint, Tête de femme no. 2 portrait de Dora Maar (B1340) – here, Dora’s eyes and parted lips appear at once aghast with anxiety and melting in love. It is perhaps most plausible that, as his friend and biographer Pierre Daix suggests, Picasso was introduced to her at some Surrealist gathering in 1935 by his friend and their mutual colleague, the poet Paul Eluard. They saw each other loosely, under the radar, until 1936. That September, Dora appeared in her first Picasso painting. “She was wearing her red coat and seems, still, like a visitor,” wrote Daix. “Then we see her long red nails, which, like her gaze and her brown hair, will become her plastic identifying signs.”**

At the time of their meeting, Dora was a commercial photographer in her late twenties. As her association with Eluard suggests, she hung with Paris’s Surrealist crowd – though her photographs would come to be associated with Surrealism, like Picasso she ultimately had a style all her own. Also like Picasso, she was a Paris transplant. She’d spent most of her childhood and adolescence in Argentina with her father (a Croatian Jew) and her mother (a French Catholic) and had moved back to France in 1926 with a foreigner’s perspective on what was most important to her: the political climate. She was multilingual, speaking French, English, and Spanish perfectly. This would have been distinctly attractive to Picasso, who never felt wholly secure in his French, learned English only in his adult life, and whose connection to his native Spain lay embedded like a heartbeat in his work. These traits – Dora’s worldly knowledge of culture and language, and her absorption in the events of the period – along with her characteristic stubbornness and unflinching demeanor, would pose Dora as opposite to Marie-Thérèse, who was placid and indifferent to art and politics. Dora took both of these subjects with her own brand of melancholic seriousness. Put simply, she was a woman with Jewish heritage living in Europe on the brink of World War II. Fascism posed a particular threat to her and her family’s life, and she felt it acutely.***

This is clear in her portraits. Even when Picasso plays with what Daix called anatomical “plasticity,” as when her head is ballooned away from her body in the 1936 drypoint Portrait de Dora Maar au chignon (B291), her expression is inescapably real; her mouth forms a hard, worried line, her eyes are big and thoughtful. She is a woman with something always on her mind. Quite famously, Picasso found other ways to express Dora’s sensitivity; among her compatriots in Picasso’s love, she is known as his “Weeping Woman,” so-called for the portrait (really, the series of portraits, which appear both in print and in paint) which shows anguish warping her beautiful features into a chaos of color, shape, and texture. Perhaps it is true that she outwardly projected this emotionality with such histrionics, and or maybe she struck Picasso so strongly that he imagined her from the inside out.

Fallen as he might have for Dora in the late 1930s, Picasso did not shed women as though he could ever be “through” with them. They thickened his life in layers of character, enhancing the deep texture of his creative psyche with the accumulation of romantic experiences. Dora would be every bit as evocative of Picasso’s creative energy as Marie-Thérèse had been (and would continue to be), but Dora’s experience as an artist, broad worldview, and knowledge of photography would influence him in new ways. As subtle as the first days of season’s change, Picasso was entering a new era.