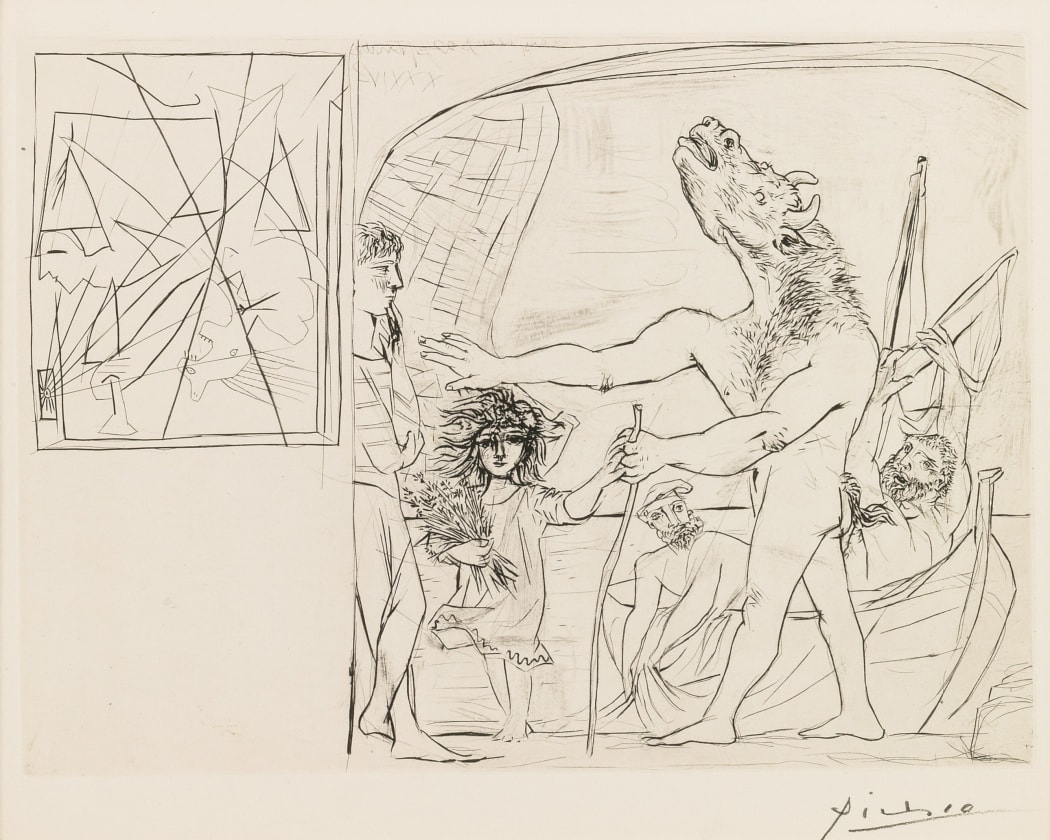

Last week we found the Minotaur in Picasso’s bedroom twice. In the first instance, he tipped back champagne with a smirk at the viewer and a beautiful woman at his side; in the second, a woman (perhaps the same one) slept soundly, while the Minotaur sat astride her and brought his face to her cheek in brazen (or maybe, aggressive) desire. In both instances, he exhibited irrepressible confidence, some prototypal formulation of masculinity. In Minotaure aveugle guidé dans la nuit par une petite fille aux fleurs (B222), we see a very different Minotaur, displaced from the bedroom or the sculptor’s studio or any other recognizable place, accompanied by a new figure: a small girl, whose task is to guide the Minotaur. Instead of a raging, human-like sexuality, the Minotaur appears anguished, his strength reduced to dependency. He reaches his hand out to the little girl, to dark space, and tosses his head back to stare, empty-eyed, before him: he is blind.

The Blind Minotaur appears in four Picasso prints, created between September and late October of 1934.* Not only does the series represent a continuation of the initial theme, created over a year prior, but it demonstrates that the connection between the artist and the symbol, between Picasso and the mythological beast, remained active in Picasso’s imagination – indeed, it seemed to have deepened, developed as Picasso did. The Blind Minotaur echoes the original series’ allegory of the artist, but then it subtracts the creature’s vision, the artist’s most uncanny, most treasured ability. In the stumbling blindness of the Minotaur, Picasso embodies his personal tensions – those of his all-important imagination; those of living in pre-WWII Europe; and those of a man sunk in the chasm between his marriage and his muse.

By 1934, blindness was certainly not a new topic of pictorial conversation for Picasso. He explored the concept in his turn-of-the-century Parisian days, his Blue Period, so-named for his monochromatically blue hued paintings and their melancholy subjects – the destitute of Paris, the un-portraitable. Critics have long poked around at Picasso’s treatment of these subjects, but the truth is simple: Picasso painted what he saw, and these are the people he lived amongst at the beginning of his career. Indeed, he saw himself within these folks – both geographically and spiritually. So the sorrow of being poor – and, indeed, blind – expanded into a question about life as an artist, a question that carried on thirty years later, into the Minotaur’s story. What is it good for? Who holds the reins, the power, in a picture: is it the blind subject, or the all-seeing artist? Ultimately, Picasso’s own, characteristically obscure words are the best answer to those questions: "There is in fact only love that matters. Whatever it may be. And they should put out the eyes of painters as they do to goldfinches to make them sing better."**

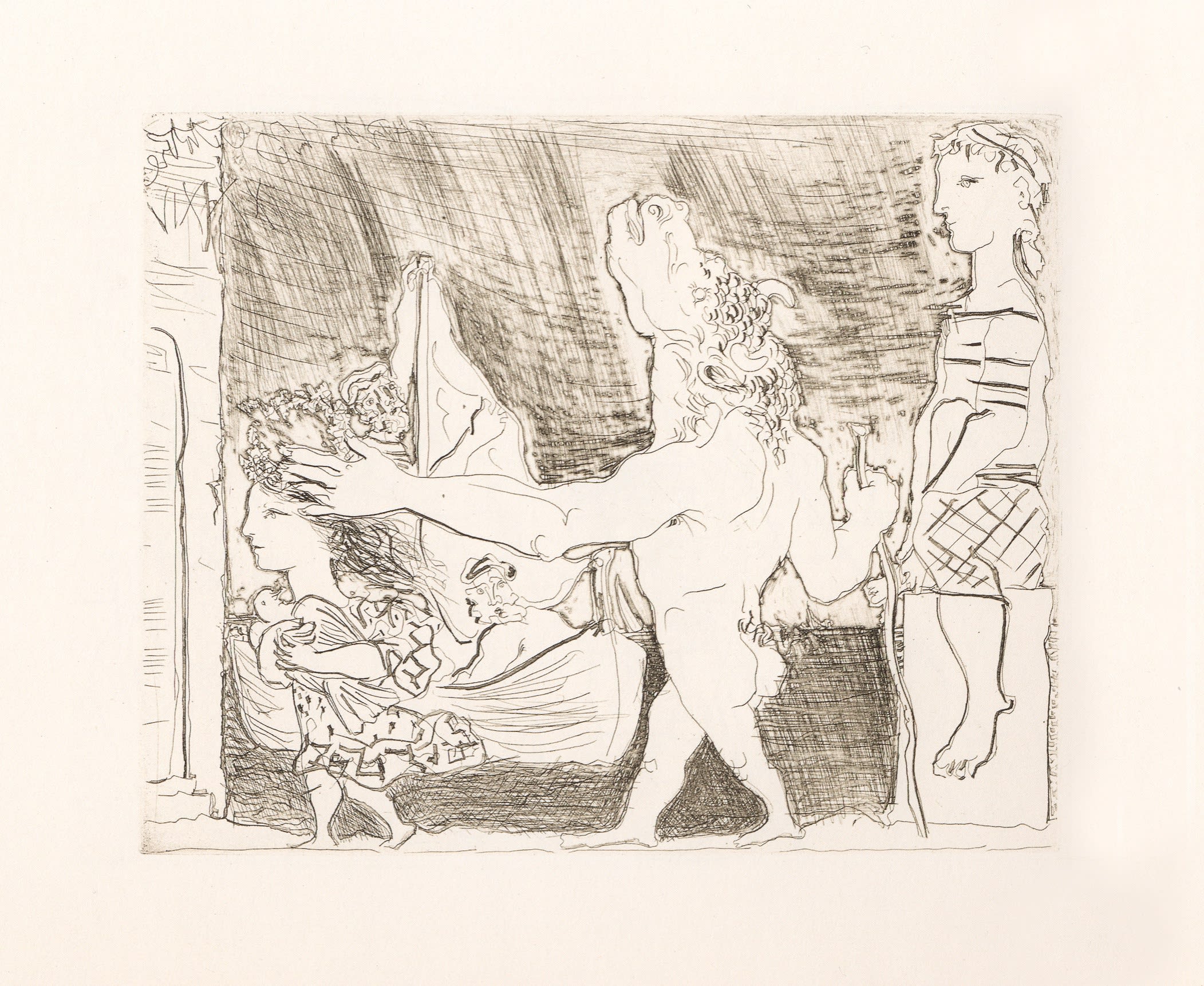

B0223 Minotaure aveugle guidé dans la Nuit par une Petite Fille au Pigeon (S.V. 96)) (B223), 1934, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches

Picasso’s words are more potent than any explication of them. What is evident is that the artist did not understand blindness as only an inability – he also saw it as an opportunity to see something else, perhaps even to see better. In Minotaure aveugle guidé dans la nuit par une petite fille au pigeon (B223), Picasso’s love is present, two-fold. Marie-Thérèse appears in a reiteration of B222’s small, guiding girl, and as a statuesque background observer of the scene. Her framing figurations, her soft, billowing hair and dress, and the dove that she carries in her arms communicate the peace of her presence, the sense of safety she imbues for the Minotaur. As she leads him out of his labyrinthine prison – much like King Minos’s daughter led Theseus in the original myth – she becomes his eyes. While this print still reads as a diary entry about Picasso’s inner-turmoil, there is a sense of resolution. In his oneness with Marie-Therese, he finds his way. And so it is not the artist’s idea that our character the Minotaur sees “better” in this frustrating state, but that he, Picasso, does. In fact, he sings.

Though Picasso attributed prints to the Suite Vollard until 1937, the four Blind Minotaurs are listed as the last of the Suite, just before the three portraits of Vollard which capstone the project. Their presence completes a kind of narrative arc whose magnitude is understood when the Suite is viewed in its entirety; true to the artist, it is a collage of figures and meanings, of diary entries and memories and daydreams and nightmares, leitmotifs all and thread together with dove feathers. For now, we cannot disclose the ending to this story. We will return to the subject in a few weeks, where once again Marie-Thérèse will represent the guiding light in a scene of blinding darkness. Before that, we’ll close the book on the Suite Vollard with one last print, and one last discussion. Until next week.

*Bolliger, Hans. “Introduction: Picasso’s Vollard Suite,” Thames and Hudson, (1956). (pp. x.)

** Perkins, Jonathan; Ravin, James G. “Representations of Blindness in Picasso’s Blue Period,” Arch Ophthalmol (2004), Volume 122. (pp. 636-639)