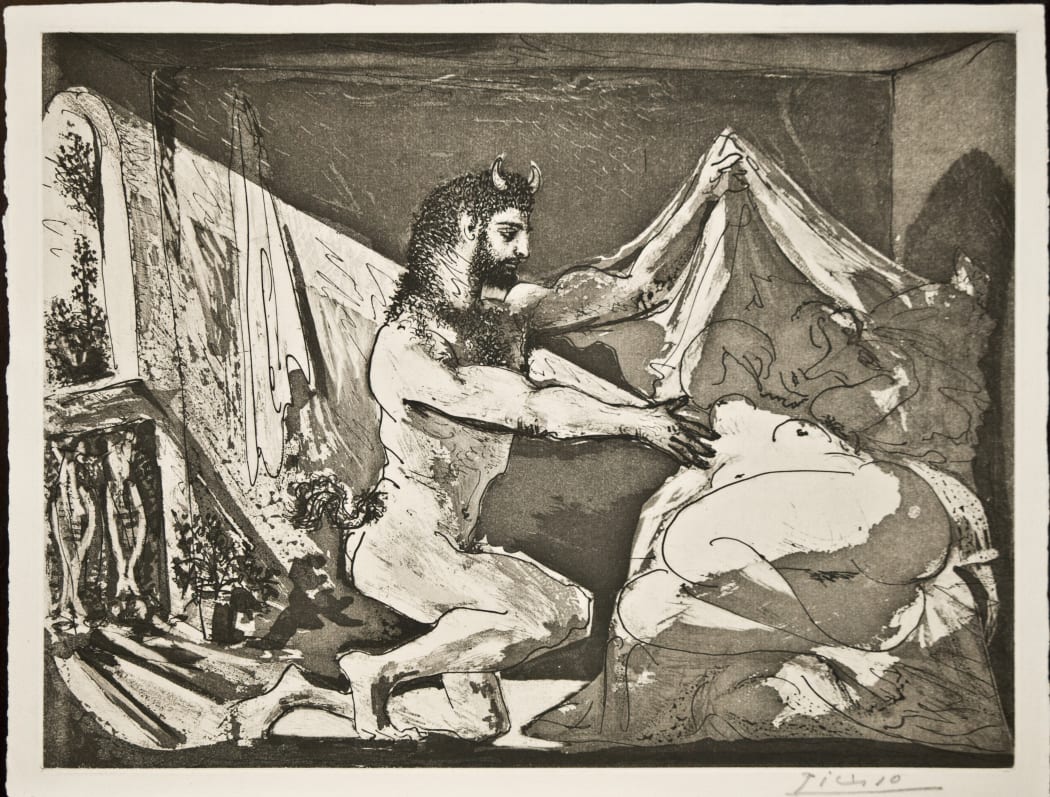

Last week, we ventured home with Picasso to Spain, entered the bull ring with Marie-Thérèse, and explored the resonance of the theme of the bullfight in 1934’s Europe, as well as in Picasso’s life as an artist. This week places Marie-Thérèse in a position perhaps just as dangerous, for all her apparent peace. In Faune devoilant une dormuese (Jupiter et Antiope, apres Rembrandt) (B230), Marie-Thérèse is instantly recognizable from her now-familiar sleepy but sensual pose: arms stretched over her head, body snuggled into the bed, and thoughts far, far away. Moonlit, a half-man, half-creature reaches out to her. Whether this is the familiar reach of a lover or the lusty one of a desirous stranger is left ambiguous; what is not ambiguous is the connection between this image, and Rembrandt’s 1659 print, Jupiter and Antiope. In that print, the Greek mythological figure Zeus (or, in the Roman version, Jupiter) peeps in on a sleeping Antiope (the daughter of Nycteus, King of Thebes). Zeus appears in the form of a satyr, or faun – just as in Picasso’s rendering, the half-human creature borrows the horns and other physical attributes of a goat.*

Beyond its visual narrative, this print calls out Picasso’s idolization of Rembrandt’s work, as well as his ambition to be grouped within the same list – that list being, of course, that of the greatest printmakers in art history. Rembrandt’s recognition in printmaking is partially attributed to the quality and detail of his artwork, but – and this is perhaps the most relevant aspect for his relation to Picasso – is also an attribute of his inventiveness, his innovation in technique. Picasso’s B230 is one of the most important prints in the Suite Vollard because it is an early suggestion that Picasso’s ranking achievements would be in the same vein. Here, he experiments with sugarlift aquatint, and despite that this printmaking technique would have been brand new to him in the summer of 1936, his execution is virtuosic.

Lacourière’s technical knowledge and artistic compatibility with Picasso opened up a breadth of expression in the artist’s printmaking. While the use of sugarlift is variable and can create a variety of desirable effects – a hard or soft line, a tone in a certain area – the most characteristic is that of the painterly brushstroke. This can be seen in the upper background grey of B230’s soft nighttime scene, or the grey shading along the nude’s face and figure. Aquatint and its sugarlift variation create meticulously calculated but spontaneous-looking prints whose tonal variety seems to drift straight out of a dream. This effect lends itself masterfully to B230, which, with its mythological theme and poetic execution, is one of the most celebrated sugarlift aquatint images in the technique’s history.

Though experimentation was instinctual for Picasso, his exposure to new techniques was tied to the development of a new friendship, one whose importance could never have been foreseen. Roger Lacourière was an intaglio printmaker stationed in Paris. He’d worked with other artists, like Matisse, throughout the 1920s, and met Picasso in the early 1930s – intersecting with the earliest phase of Suite Vollard creation. In those pre-Lacourière years, Picasso worked with a printmaker called Louis Fort. Fort was a good technician and was important in the editioning of the Saltimbanques prints. But when Picasso met Lacourière, there was no question who he would partner with to create the rest of the Suite Vollard. The pair reworked and completed the early plates Picasso had started with Fort, and when Vollard’s book of Picasso’s prints was published in 1939, all the editions had been done by Lacourière.

The poeticism of this print may also have been a result of another development in Picasso’s social world. Much like he had thirty years before, in the 1930s Picasso lent his company to the poets and intellectuals of Paris. These individuals were foremost Leftists, formed in radical opposition to the threat of faciscm, and the group was exemplified by its constituent members, the Surrealist artists. These artists’ work questioned the very structures of the everyday, of the un-questioned. Though Picaso was not a Surrealist, his association with them was cemented by a few of his most important mid-career friendships. One of these was with the avant-garde poet Paul Éluard. Of all the Surrealist poets, Éluard was the most interested in visual art (perhaps to his detriment – his first wife, Gala, famously left him for Salvador Dali). Éluard and Picasso harmonized in their multidisciplinary mindsets; Picasso, for his part, was a curious reader and wordplayer, and honored the sensorial connection between language and visual art. In June of 1936 Picasso composed Quatre sujets pour la barre d'Appui (B295a), a print divided in four illustrating a collection of poems by Éluard dedicated to the poet’s second wife, Nusch. The rich, romantic result was completed shortly before the execution of B230, distinguishing these prints as Picasso’s first forays into aquatint and sugarlift.** Three of the four of these prints can be seen above, with cancellation marks notating the limitedness of their editions.

Discussion of burgeoning techniques and the powerful B230 typically capstones a discussion of the Suite Vollard, but we still have much to share. In fact, the half-man creature that appears in this print gestures back in time a few years to the appearance of another mythological creature, whose presence establishes the second major theme of the Suite, as yet unexplored: the Minotaur. More on that next week.