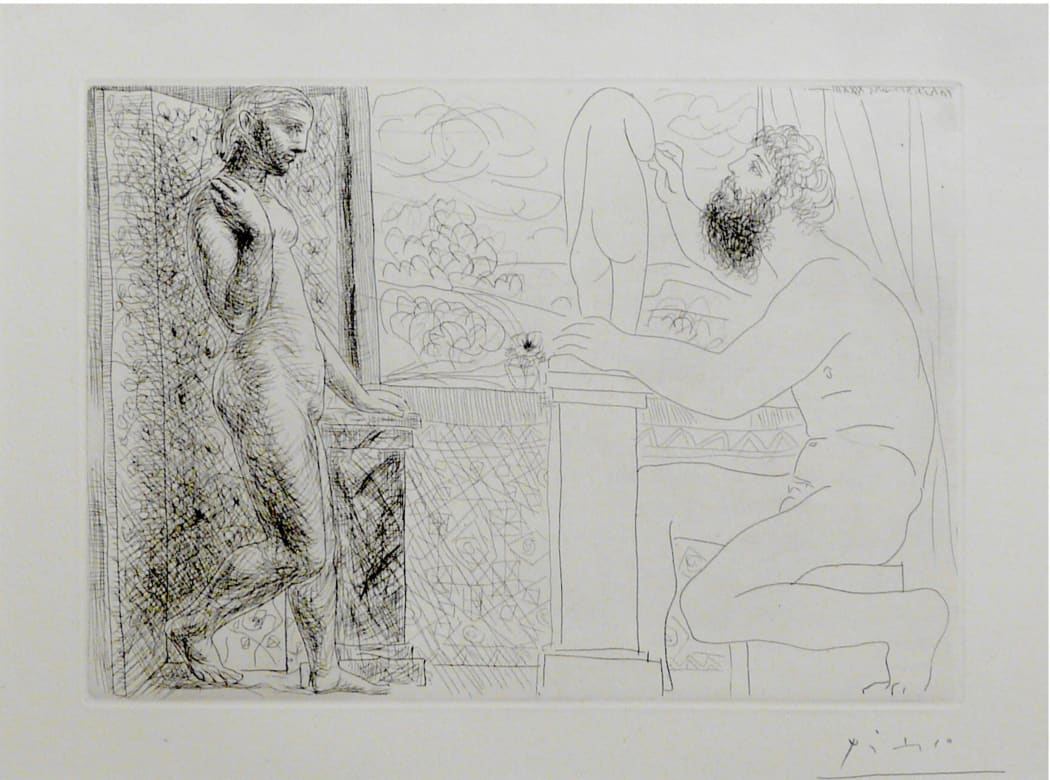

In popular culture and the art community alike, Pablo Picasso’s face is as recognizable as his artwork. He was well and frequently photographed throughout his life, so we know that he was a short man, with large, dark, intense eyes and a mouth that cut into a wide smile as easily as a scowl. There is no visible trace of that figure in the naked man pictured above, with his unruly head of Grecian curls, thick beard, and virile body – and yet, this figure is Picasso. Picasso as he saw himself, as he felt himself to be. Considering that Picasso made this plate in 1933, when he was over fifty years old, the grounds for this position seem shaky – until one peruses the Suite Vollard and sees the echo of this ancient-looking artist in nearly half of its images: sculpting, lounging, contemplating, and tumbling into bed with his models. That these models often appear in the likeness of Picasso’s young lover, Marie-Thérèse, emphasizes the psychological connection between this ancient-looking figure and the artist who created him. It is not coincidental that at this time, Picasso began dating his prints – partially to keep track of them, and partially to keep track of the sequences of his life that they illustrate.

In 1933, Picasso completed sixty-two prints for the Suite Vollard project. Forty of those prints deal with what has come to be known as the Sculptor's Studio, as shown above (another six would be added to this series in 1934). Sixty-two – or even forty-six – prints would be a significant amount for an artist to create over a few years, or even a career; and this is only a fraction of the Suite Vollard. From September 1930 to December 1935, Picasso completed ninety-six prints.* This was a creative frenzy, both in rapidity of production and in the technical evolution of the artwork created. Because these prints were created in such a short period of time, they “read” as a diary. In the same way that in a diary we read the word “I” and hear the author self-reflecting, in the Sculptor’s Studio series, we see the mythological, almost godly sculptor and hear Picasso acting out his most interior reveries.

What was so significant about the subject of the sculptor for Picasso? A few years prior to the creation of these prints, Picasso had purchased a country retreat: the Château de Boisgeloup in Normandy, forty miles outside of Paris.** He had tired of his annual summer pack-up-and-relocate, at one time creatively freeing and now enforced by his duty to family life. Tucked away across the grassy grounds from the sprawling pale-stoned home was a stable. Picasso converted the stable into a studio, thus separating his work space from his home life – or, you could say, separating Marie-Thérèse from Olga. As we wrote more about here, in this much bigger space Picasso found himself able to experiment in scale with sculpture, and some of those coming out of the Boisgeloup studio manifested as busts of women with stately Roman noses, regal but sleepy eyes, and anatomically displaced proportions.

Picasso seemed to be fascinated with more than sculpture; the idea of the sculptor, the maker and modeler, intrigued him. He was beginning to recognize himself in this role, literally – perhaps figuratively, he always had. It is not strictly the technical ability to work with materials that makes the sculptor great, but his capacity to create – his understanding, his manipulation of the psychical and metaphysical concepts we call reality. In this, Picasso had always been proficient.

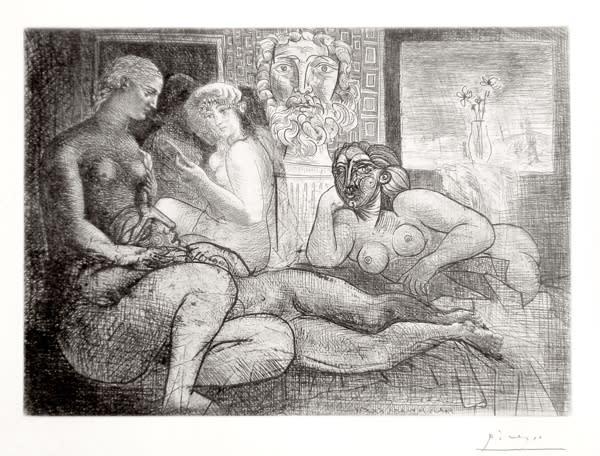

It is also telling that Picasso’s sculptor figure does not always appear young and virile. In one of the works added to the theme in 1934, and one of the most rich of the Suite Vollard, Quatre femmes nues et tête sculptée (B219), the sculptor appears aged, wide-eyed. He no longer has the autonomy of his strong body, but is the head on the pedestal. The sculptor has become the sculpted. The foregrounded women are lined in a gorgeously rhythmic flow that centers the wizened sculptor’s monumental head, and holds him apart from their group of living, breathing bodies. Notably, 1934 was a year of dissolution within Picasso’s romantic relationship with Marie-Thérèse, who had started as his secret lover, had become his inspiration and his escape, and had ended up exposed, the mother of his daughter, Maya, who would be born in 1935. For Picasso, the relationship had dimmed. In B219, the sleepy figure resembling Marie-Thérèse is cast in textured shadow, while the bust of the sculptor is awash in triumphant light.

While the Sculptor's Studio as a collective represents the most continuous subject within the Suite Vollard, the Suite’s prints were by no means relegated to telling one story – its graphic themes recoded the artist’s thoughts and feelings, which rose and quelled with his days. Next week, we will take a look at some of the plates completed throughout the seven year creation period of the Suite Vollard, those whose belongingness to the series lay less in a story arc and more in their resonance with a few of the artist’s most recurring preoccupations.

* Bolliger, Hans. “Introduction: Picasso’s Vollard Suite,” Thames and Hudson, (1956). (pp. x.)

** Waldeck, Stefanie. “Pablo Picasso’s Former Studio in an 18th Century French Chateau…” Architectural Digest, (October 2019).