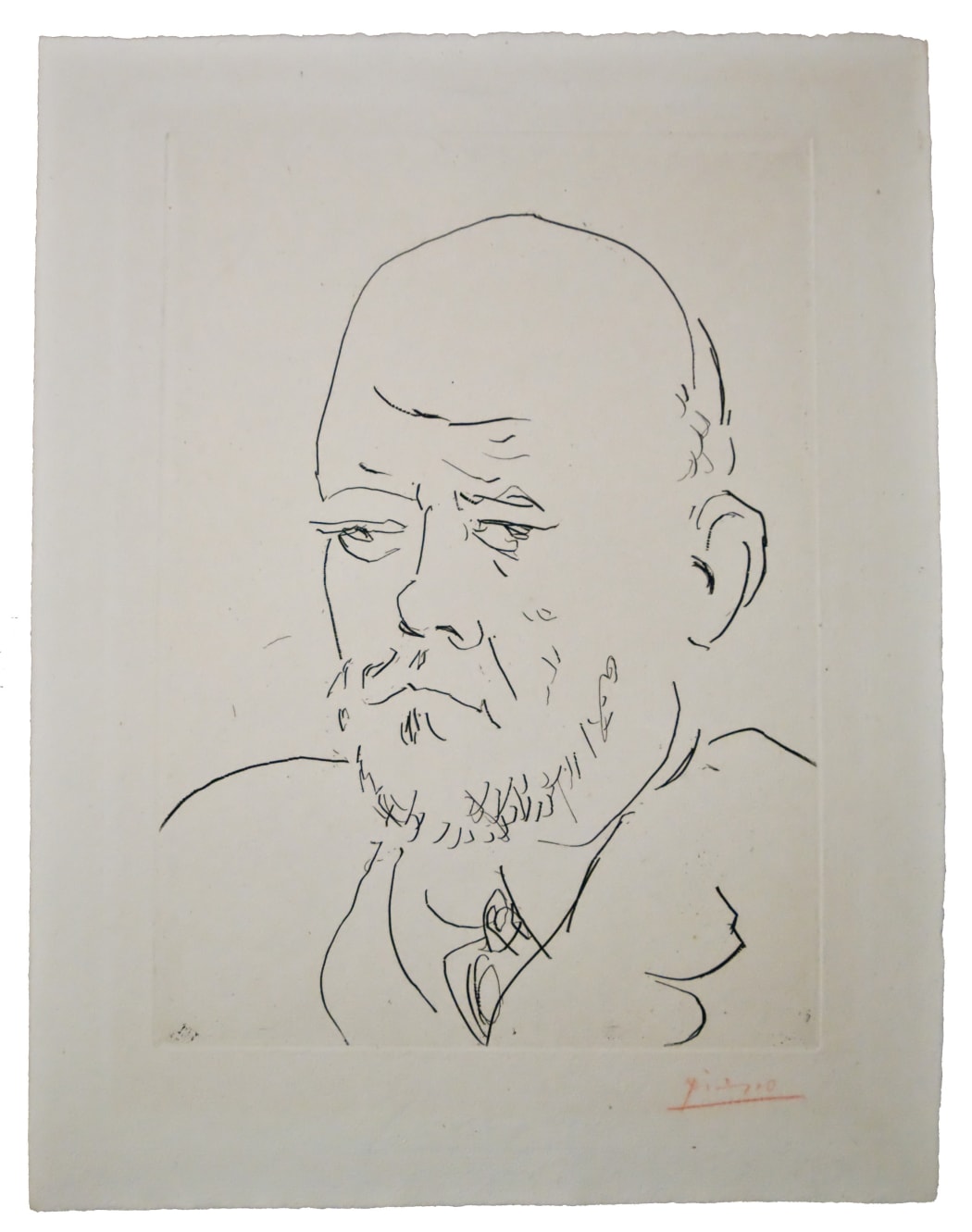

Throughout our stories of Picasso’s life in art, we have returned time and again to the beautiful muses-turned-models which inspired and populated his artwork. With that context, you may be wondering how the bald-headed, sunken-browed subject looming over these lines in Portrait de Vollard IV (B233) found himself memorialized in print, etched with equal intention and care as the Marie-Thérèses and the soon-to-be Dora Maars. This etching, signed in 1937, is one of four contemporaneous representations of the rightfully famous – rightfully inspiring – art dealer, Ambroise Vollard.

Though imperative to the history of impressionist and modern art, Vollard is not always a name casually known. So, who was he, and how did he become such a fixture? In 1890, at twenty-three, Vollard moved to Paris to finish out a law degree. Bright, attentive to detail – it could not have been a lack of intelligence that handicapped his marks at school, but a lack of interest. Paris invited its own interests, as he was about to discover. At the time, a Manet painting could be found at a small shop in the Latin Quarter for less than 1,000 francs – Renoirs for 400.* To cultivate a collection, one needed less money than patience, a good eye, and time to scour. Vollard naturally had two of those attributes and so gave up on law to make room for the third. Years of hard work and drive crystalized into expert vision, and by the turn of the century his name was associated with works by Paul Gauguin and Paul Cézanne; Renoir, Monet, and Van Gogh; even our friend Edvard Munch.

Vollard met Picasso as early as 1901, when he and his roommate Max Jacob were still burning sketchbook pages to keep their one-bed rented room warm. He was responsible for one of Picasso’s first (and, though technically unsuccessful, highly significant) shows in Paris. It was both an opportunity for a larger audience to see Picasso’s work, and an authoritative nod of recognition toward the twenty-year-old artist – three years younger than Vollard had been in his own early Paris days. Vollard had a penchant for pegging potential early, and fittingly he was enamored with Picasso’s Pink and Blue periods of painting, especially his Saltimbanques series.** He was not, however, as supportive of Cubism, which took its root in Picasso’s artistic imagination around 1915.

Even when Vollard was not so interested in showing his work, Picasso and he maintained a relationship. For Vollard was more than a dealer – his opinions and his gallery were at the center of the art world. As common ground for many important artists, he facilitated friendships, stoked rivalries; he created a casual circle of some of the most important names in art history. It seems natural that as Picasso’s reputation rose, as his technical repertoire became more robust, and as his stylistic tendencies developed from Cubism into neo--classicism into the anatomically chaotic “bone” period (what some have called the beginning of his “surrealist” bout, though the artist himself certainly did not), Vollard’s interest would be piqued.

As alluded to in our story about Albert Skira’s Ovid publication, Vollard’s approach was parallel to Picasso’s work on a suite of prints illustrating the Metamorphoses. Vollard – no longer a young, striving man, but an accomplished, distinguished figure – was interested in art publication himself. And Picasso was no longer a young, striving man either; he was nearly fifty years old, and a far way from the blooming artist eager at any chance, burning his sketches to stay alive. Whether initiated by Vollard’s conquest for exclusive Picasso prints, created at what might have been conceived as the height of the artist’s career (for who could predict the work that Picasso would make into his old age?) – or, more likely to this writer, by Picasso’s desire for paintings within Vollard’s collection; a deal was spurred between them. The grounds were clear: this would be an exchange between two great businessmen. Picasso would make 100 prints for Vollard, and Vollard would relinquish a few key paintings of Picasso’s choosing. Vollard’s acceptance of this deal is indicative of the value he foresaw in the prints to come – prints created over seven years, ranging in style, technique, size, and subject, but all grouped under the collective name, Suite Vollard.

Some of Picasso’s most incredible, well-known prints were created between 1930-1937, coinciding with the years he spent working on the Suite Vollard. The bulk of the series was completed in 1933-34 – coincidentally, also the zenith of the artist’s love affair with the much-younger Marie-Thérèse. The relationship’s bell-curve of passion is well-documented in the series, as well as the artist’s overture in sculpture and career-long preoccupation with classical mythology. The relationship of all of these historical factors are expressed in two major themes present in the series: the sculptor and the model in his studio, and the minotaur.***

Over the next couple of weeks, we will explore standout prints within the Suite, examining their themes and techniques, and, of course, unpacking the journalistic stories embedded into their scenes.

* Bollinger, Hans. “Introduction to:” Picasso’s Vollard Suite, Abrams. (1977) (pp. v)

* Florman, Lisa Carol. In Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s, Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press (2000). (pp. 70-138)

*** O’Brian, Patrick. Pablo Ruiz Picasso: A Biography, W.W. Norton (1994). (pp. 305)