This week, we’ll take a little break from Picasso’s inexhaustible tome of romantic entanglements, and instead take up with what is of course an even more tantalizing subject: what he was reading at the time. Picasso was (perhaps unfairly!) not known for a taste for literature – perhaps more so for a taste in friends who were. One of these friends, a Mr. Skira, was an aspiring publisher, and aligning with the popular movement of reinvigorating and redistributing the classics, requested that Picasso create the illustrations for his upcoming Ovid publication.* The model of literary text accompanied by contemporary artwork was not exactly novel, especially for Picasso – this would be the artist’s nineteenth book project (you can read more about one of these projects here.)

Though Ovid’s Ars Amatoria(The Art of Love, a three-volume handbook on how to keep your mistress happy) may have seemed more up Picasso’s alley, he was asked to portray scenes from The Metamorphoses. It is distinctly ironic that in 1930 – at the turn of the decade, with half of his life before him, a marriage and a mistress both on the precipice of dissolution, and an amorphous style that was still, after all these years, on the run from its artist – Picasso would pick up the Metamorphoses project. Perhaps his evocations of its scenes and characters were a product of a deeper understanding, an understanding of the powerfully entropic force at work in life’s ongoing change. On the prints created for the text, the author of Picasso’s catalogue raisonné, Christian Zervos, commented, “These are not properly speaking illustrations… They are personal interpretations of the world that Ovid had envisaged.”**

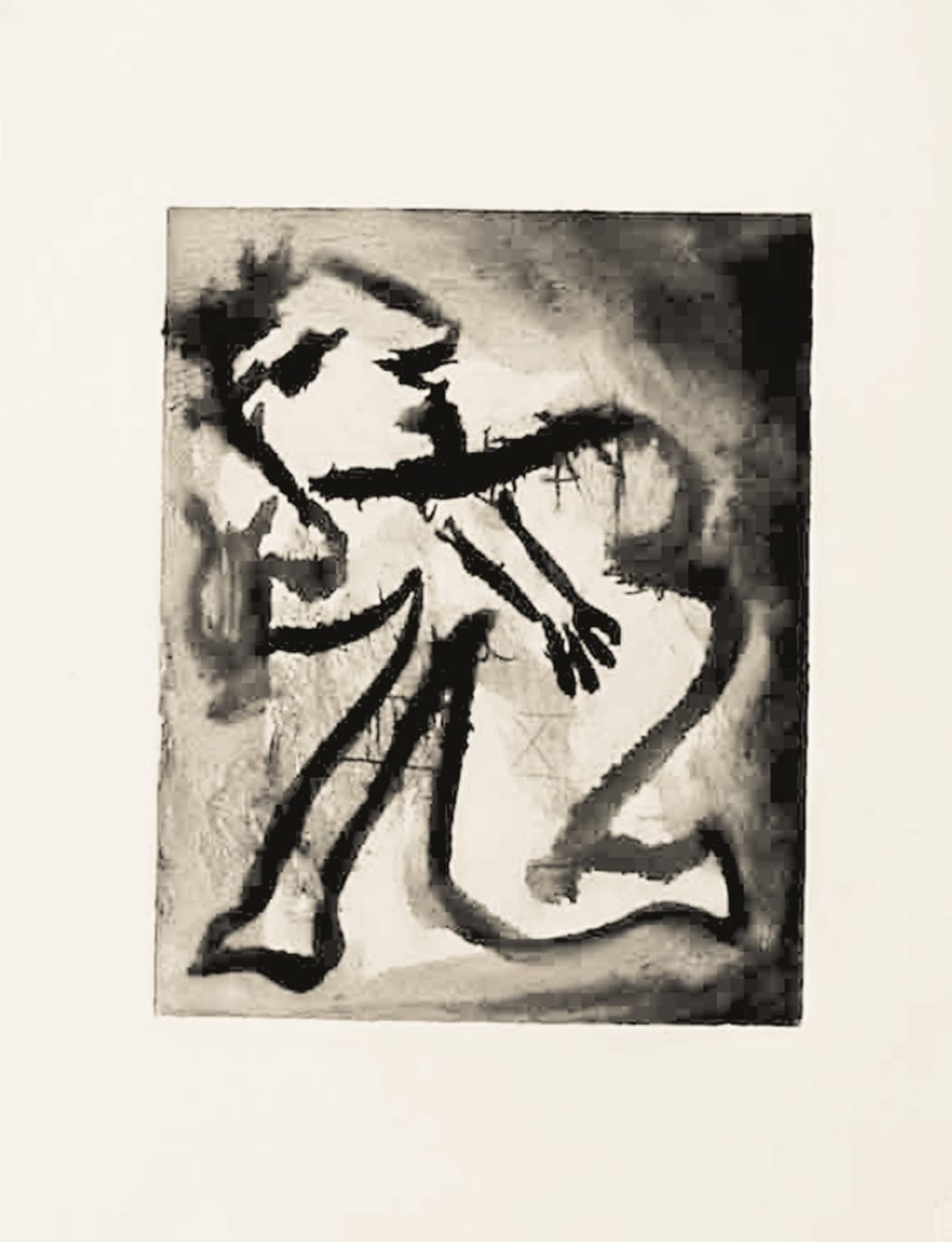

For those that skipped their liberal arts degree, Ovid’s Metamorphoses is a 15-book epic poem, written around 8 AD and following in the tradition of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and Virigil’s Aeneid. Except where those classical texts celebrate the hero’s journey and other grandiose themes befitting an epic poem, Ovid took his content a somewhat scandalously alternative route. His poems begin with the creation of the world and continue on by winding through the stories of its various inhabitants – stories that celebrate (at times problematically) people’s heroic and debaucherous endeavors alike, reserve of moralization. In the tenth book of the epic, we are introduced to the musician Orpheous. Creative, impish, a hit with the ladies, he was a naturally attractive, likely resonant subject to Picasso. Despite the late appearance of this character in the text, Picasso worked this plate first, setting the style for the rest of the book’s illustrations.*** These iterations of Ovid’s Orpheous preceded the above-pictured monotype depiction of the musician, Orphée, ou le poète. II (Ba0541), created in 1933.

Skira’s book was published October 25, 1931, Picasso’s fiftieth birthday. Though it achieved less commercial success than its collaboration had warranted, the project served a perhaps more important purpose. With the book’s fifteen full-page illustrations, fourteen alternate plates (which do not appear in the book), and many half-page illustrations, Picasso was consumed for almost a year in the printmaking process.* While certainly not the beginning of his printmaking career, the Ovid project hallmarked a new chapter – one in which Picasso began his own hero’s journey: from aspiring master painter to unsuspecting master printmaker. The coming years would demonstrate Picasso’s growing fascination with the artistic possibilities of the print.

Of course, this story cannot begin without the introduction of a leading character – Ambroise Vollard, one of the most important French dealers in modern art’s history. Vollard had been Picasso’s dealer in turn-of-the-century Paris, and in the intervening years had gotten a taste for printed editions. Somewhat unfoundedly, he considered his history with Picasso a warrant for exclusivity of his work and, naturally, was not happy to learn of Skira’s book – especially since Skira was far lesser-known, and far less impactful on the art world than himself. Vollard recognized the immeasurable artistic potential still to come in the then-middle-aged Picasso, and he would make it a point to ensure that his reputation was the one which benefited from it.

We’ll tell you more about the ambitious dealer, and more about Picasso’s most celebrated print collection, in the weeks to come.