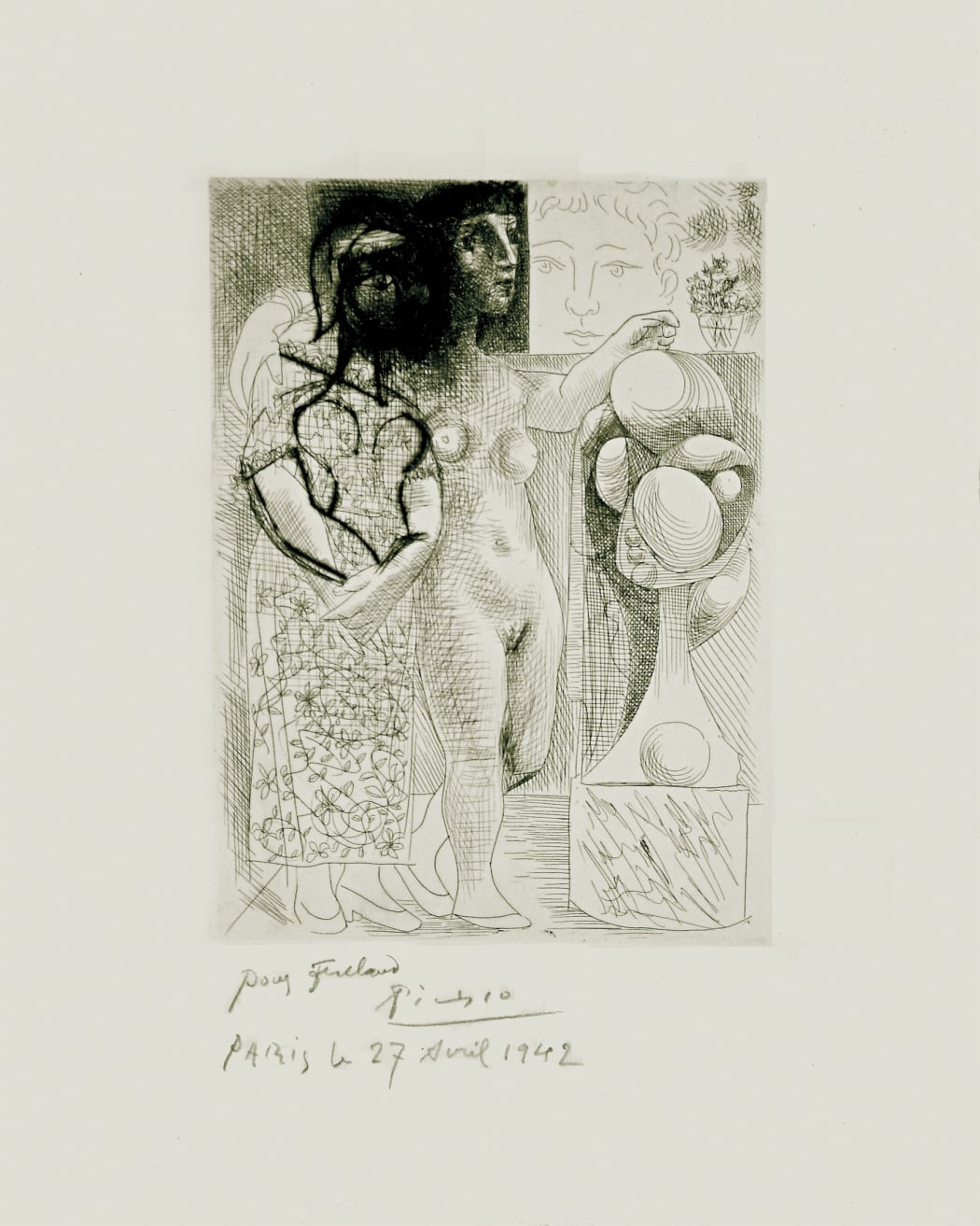

Last week, we wrote about two of Picasso’s emergent artistic fascinations, corresponding to his relationship with his golden muse, Marie-Thérèse Walter. The first of these – sculpture – would not only take him to experimental heights in a new form, but would permeate other forms. We see this story play out in the etching and drypoint Muse montrant à Marie-Thérèse pensive son Portrait sculpté (B257), wherein the subject – a suspiciously Marie-Thérèse-looking figure – presents the majesty of sculpture to another, dowdier figure, who seems resistant to its classical appeal, uncomfortable wrapped in the naked arm of her companion. It is this figure that gestures to the other development in Picasso’s art – the tormented pictures of his wife, Olga.

Preceding this print was Picasso’s 1929 painting, Bust of a Woman with Self-Portrait. The visual subject matter is similar: sculpture rendered two-dimensional, backgrounded by a knowing face. Here, the “bust” of the “woman” is not the epitome of beauty, but distorted, shrieking, violent in madness. She is Olga, as Picasso’s artistic imagination captured her, bearing witness to the drawn-out end of the marriage in which she put so much stock. Her hair juts away from her face like the angry teeth of a comb. Even in this small detail, Picasso mocks his wife – she had begun to dye her hair black, and in this portrait, he re-dyes it in the sunny warmth of Marie-Thérèse’s chignon.*

These two images – created over a span of four years – are two members of a large group juxtaposing the women of Picasso’s life as he entered a new decade: Olga, manic, and Marie-Thérèse serene; Olga, teeth sharpened and barred, and Marie-Thérèse, asleep. They speak to an internal conflict within the Picasso family. And so, we return once more to the question posed at the beginning of our chapters on Marie-Thérèse: how long could the relationship last in its bliss, before Olga found it out?

Or, perhaps she had known, on some level, all along?

In either case, three blows hastened the certain end of Olga’s disillusionment. In 1930, Picasso and Olga alike were perturbed to learn that the artist’s former girlfriend Fernade Olivier had published a memoir under the upsetting title When Picasso Painted Kitsch (name to change as feelings cooled down). In the book, Fernande capitalized on her proximity to Parisian Bohemia through Picasso. She spared no detail about his younger-years activities – opium, parties, women: prostitutes, models, and mistresses.** Olga was mortified. The plain truth was in front of her: if that was the way Picasso operated in his eight-year relationship with Fernande, why would their marriage be any different? (Picasso would later concede that the book was valuable, an important documentation of the magical Bateau Lavoir period – a concession with which this writer heartily agrees.)

And then, in 1932, the Galeries George Petit held a Picasso retrospective which is largely believed to have been the most public revelation.** Picasso hung the exhibition himself, positioning his Blue and Rose period works alongside Cubism, neo-classical images of Olga as the primordial mother, and a slew of Marie-Thérèses – naked, sleeping, lounging, playing; adored. Olga would have had to walk through the exhibition with her eyes closed to not see the truth. Perhaps she’d always known about Marie-Thérèse’s presence, but it was only then that she saw her appearance, and the degree to which she had taken Picasso’s heart.

Despite their prolific arguments, the anger and anguish depicted in Picasso’s portraits, there was no big ending moment to the relationship. They slowly and painfully separated between 1934-35. Despite promises to Marie-Thérèse that she would one day be his wife, Picasso refused to divorce Olga – be it for any number of reasons: pride, indifference, or because he did not want her to win half of his money.*** For her part, Olga refused to accept the reality of the split, of the dissolution of their family life. To the displeasure of many women to come, the Picassos’ marriage would remain intact until Olga’s death in 1955.

But long before that, in 1935, the final blow: Marie-Thérèse was pregnant. Olga packed up Paulo and left the Paris apartment. Coincidentally, this event served less as a disruption to the marriage, as to the affair. Picasso experienced his own disillusionment – with Marie-Thérèse. As golden a muse as she was, she was not his final love. Rather, she sang the interlude from conventional life back to the life of an artist.