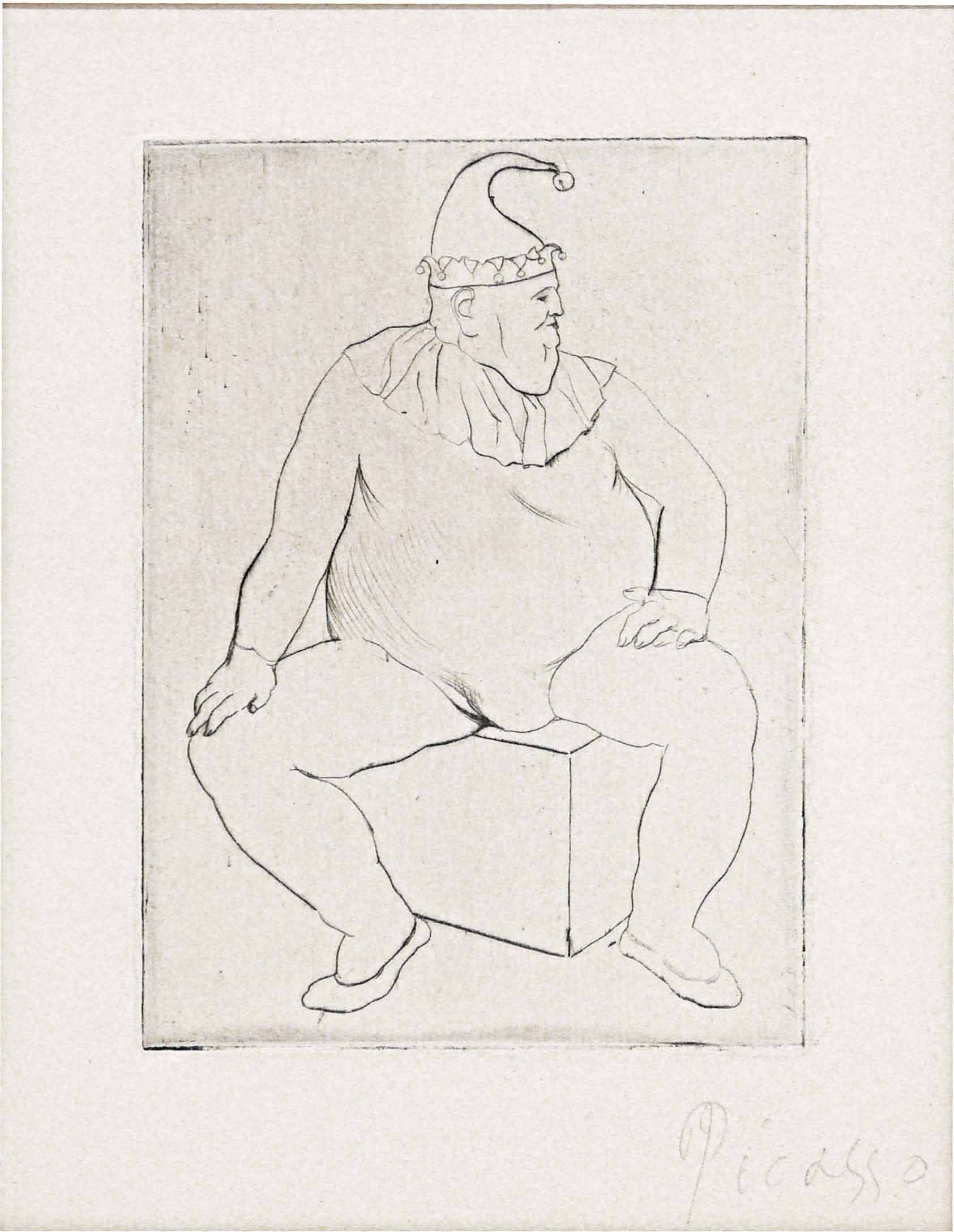

We left off with a long look at Picasso’s Ecce Homo, in which the enthroned artist sits on a stage surrounded by his court. Now, let’s shift our gaze to the group of figures on Picasso’s far left (our right). They have the medieval glean of jestors, shepards, bards – recalling art historian Peter Read’s wry observation that Picasso’s closest friends of yore were “sometimes presented as jesters or courtiers sycophantically circling Picasso, the all-powerful genius.”* Really, those “courtiers” included some of the greatest minds of modernity, and they were gravitationally pulled to Picasso not because he was more powerful than them, but because, in his dynamism, he was one of them.

Some members of the court: poets Paul Éluard (spur to the Surrealist movement) and Jean Cocteau (whose ties to the theater and Russian ballet would lead to Picasso’s next chapter); painters André Derain, Georges Braque, and Le Douanier, Henri Rousseau; important collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Ambroise Vollard. And, of course, the Bateau Lavoir poets, the original Bande a Picasso: our familiar Max Jacob; the poet and art critic André Salmon; and that charismatic figure, monumental to French literature and 20th Century thought, who lived in Picasso’s sketchbook more than any other friend, Guillaume Apollinaire.

It is no coincidence that Picasso imagines the bande in particular within Ecce Homo, his production of his rise to an artistic greatness on par with Rembrandt. He met them when he was fresh out of Barcelona, and they were his introduction to both the theater and circus in Paris. Back then, they took those styles of high and low performance home, making-believe their old Bateau Lavoir into a glamorous gallery wherein the poets would take turns parodying famous artists – Degas, Renoir, Baudelaire – coming up the creaky steps of the ramshackle tenement to lavish praise upon Picasso’s artwork. On his friendship with the rambunctious writers, Picasso simply said, “The painters are too stupid and their conversation is boring.”*

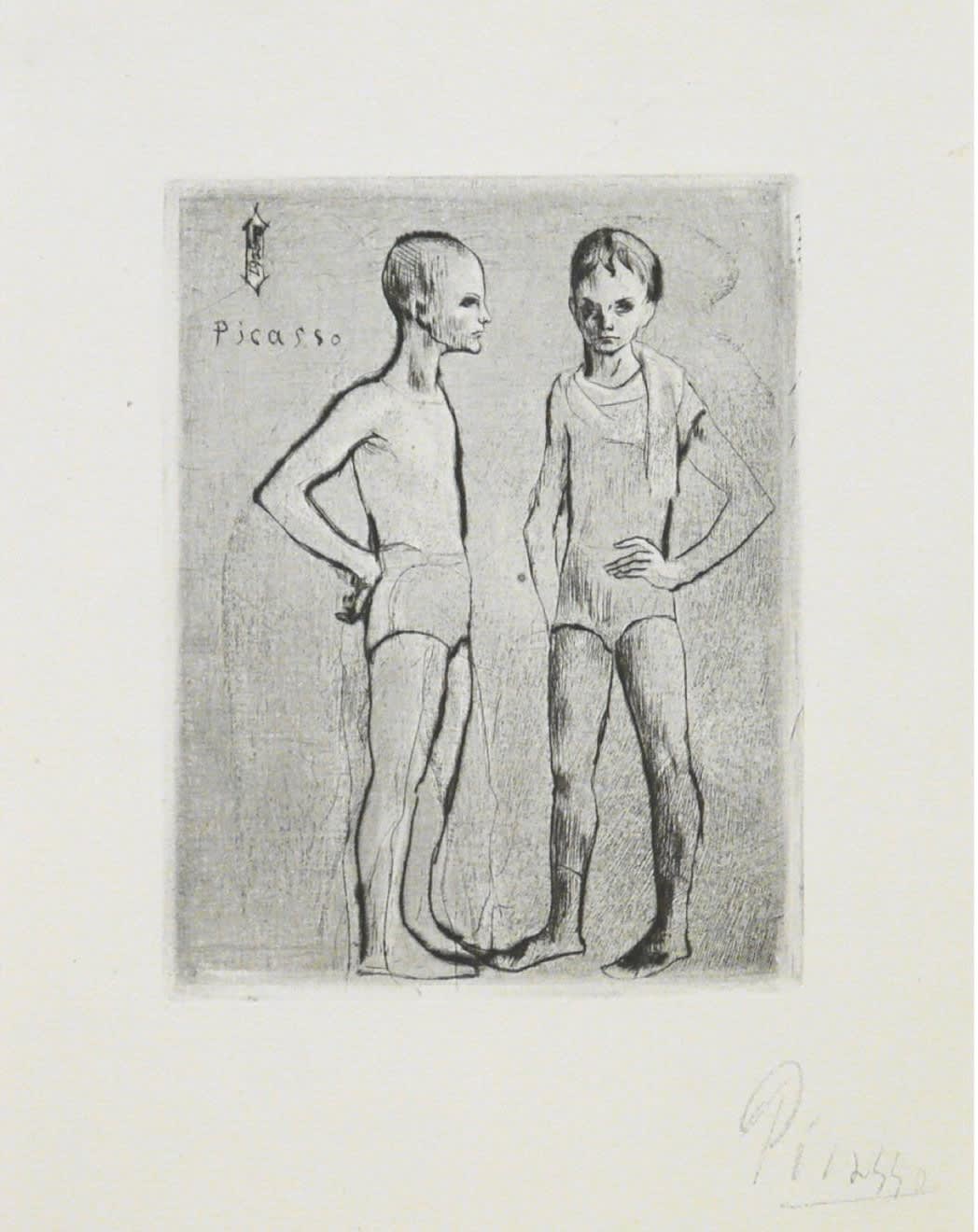

Pablo Picasso: Le Saltimbanque au repos (Bloch 10), 1905, drypoint, 12 1/4 8 3/8 inches

Even after he moved out of the Bateau Lavoir, Picasso’s favorite conversationalist was Apollinaire. They were both immigrants, both churning with quick wit and avant garde ideas – and they found unity through a shared vocabulary. This was the blooming language of modernism: anarchy, urbanization, disruption through its nontraditional, non-Western forms. One spoke verbally, the other pictorially. Their meetings became daily rites, unmissable. One afternoon, when Apollinaire did not show up, Picasso sent him a note: “Dear Guillaume. We’re wondering where you are. Are you by any chance in Poland? Or convalescing in Vésinet?” For Picasso, the only permissible excuses for absence were near-death, or an Eastern vacation. He signed the note, “Picasso the painter and your friend.”* These things were inseparable.

Indeed, of that court of big names, Apollinaire in particular was essential to Picasso’s artistic DNA – so moving forward, we’ll look at their friendship, set deep but cut short, as well as the sometimes controversially regarded work created as its result.