We last left wondering whether Mademoiselle Léonie was more than an acrobat-model, more than a mistress in Max Jacob’s book – but was rooted in memory.

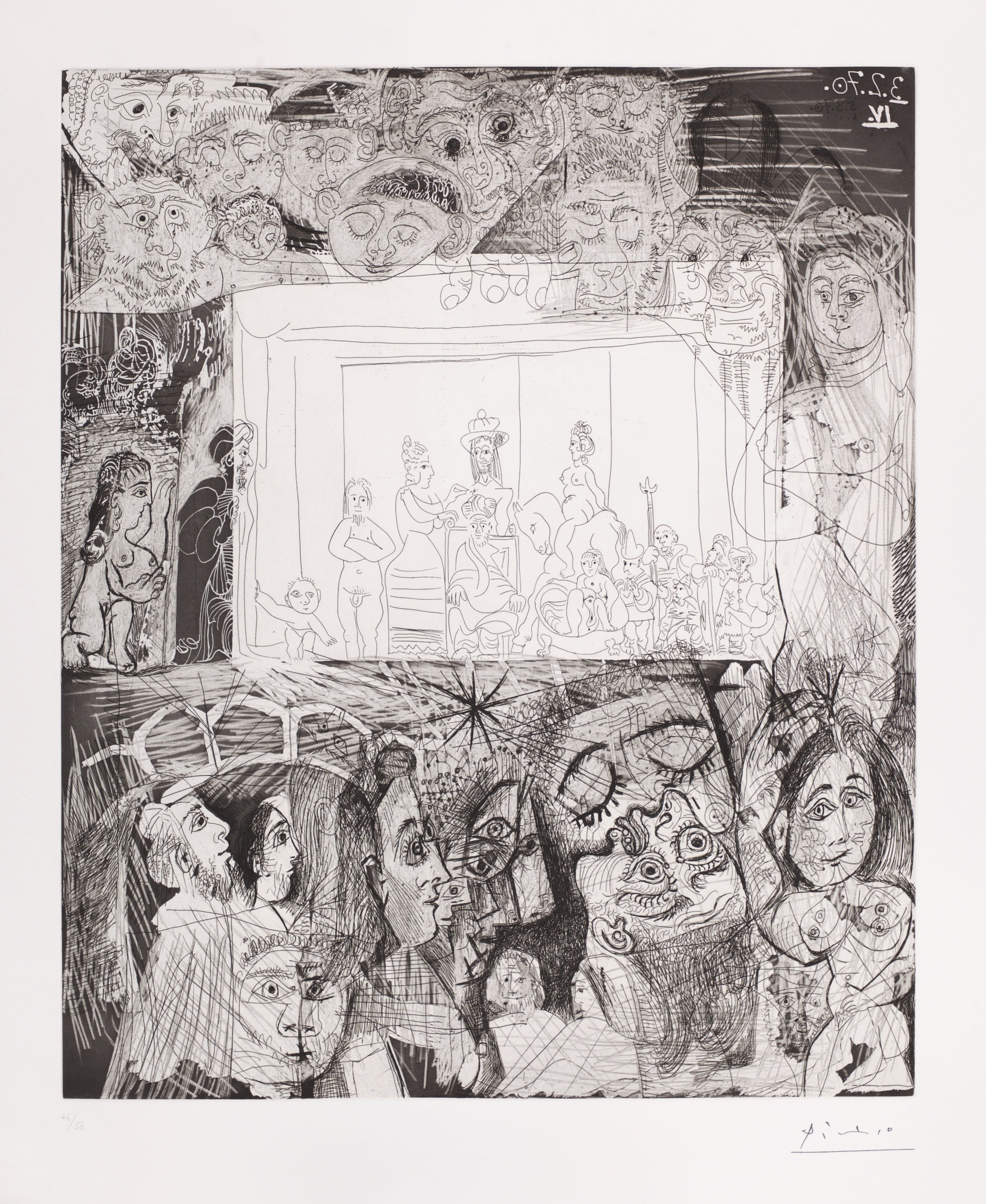

This inkling is based on a print made in 1970, Picasso’s autobiographical grande finale:“Ecce Homo” d'Après Rembrandt (B1865). In it, the spectacle of an adoring, many-faced audience is a smiling old man, enthroned center-stage amidst an ensemble of figures. He is Picasso, looking back over his almost 90 years, and the figures are the characters whose relationships gave life to his story – friends, lovers, models, and even a baby version of himself. It is a psychological picture that elevates and remembers, both in the sense that Picasso could, with the work of his life before him, consider himself as equal to those artists he had once emulated, like Rembrandt; and in the recognition of the importance of the people he’d met along the way. He imagines his greatness coupled with their surrounding presence. One eye-catching figure sits behind him, naked, astride a horse.

She’d lived in his psyche a long time – since his teenage years in Barcelona. It was there that he was initiated into nightlife and met her, his first mistress: Rosita del Oro. Rosita was the surprising combination of prostitute and well-known equestrienne at the circus, featured on its poster ad. What is known of their relationship is pieced together through insinuations in letters and notebook sketches and the anecdotes of old friends, all of which suggest that Rosita was more than just an occasional lover.* Their physical relationship ended when Picasso set his sights on Paris, around 1900.

Pablo Picasso: "Ecce Homo" d'Après Rembrandt B1865, 1970, etching and drypoint with scraper, 26 3/4 x 26 1/8 inches

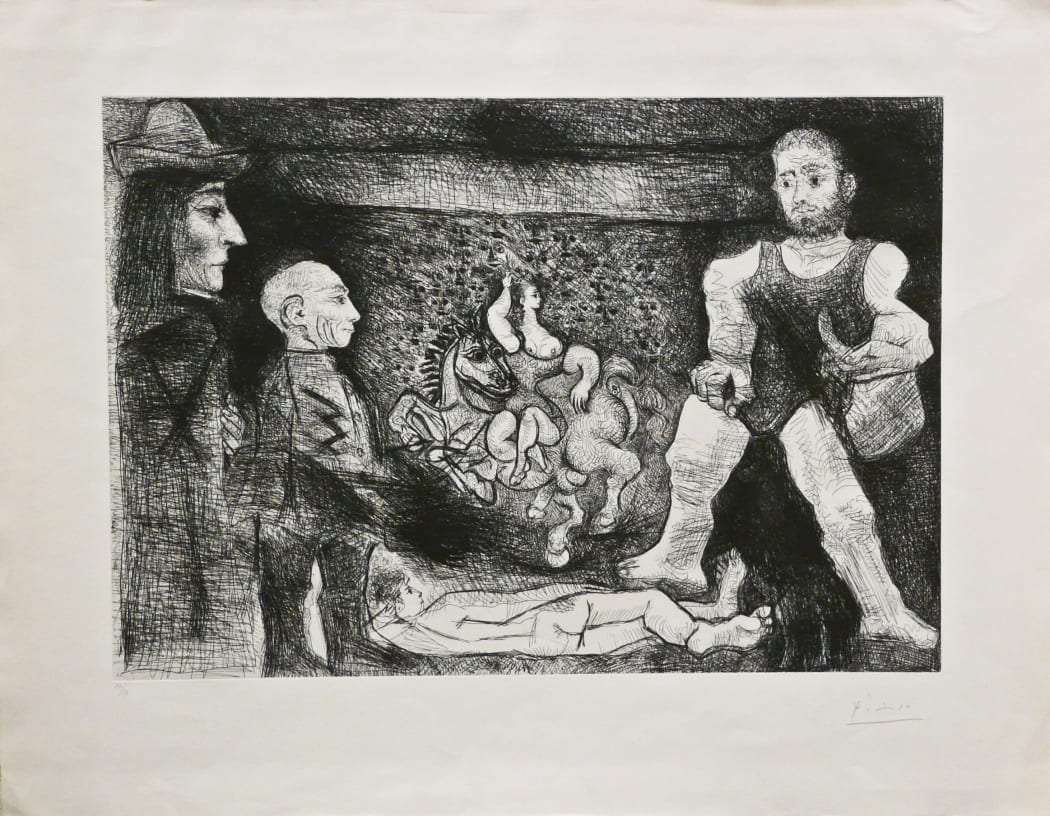

Rosita was resurrected a lifetime later. First in 1968, in his 347 Suite, a group of prints made in a matter of months at a prolific rate. These were a fever dream of memories, spilling out in unlikely scenes taken from his life. Rosita appears in the frontispiece image on a bucking horse, ever the equestrienne star (B1481). And then, in the prints with similar themes made a few years later known as the 156 Series, she is brought out again. Of course, in Ecce Homo: the circus performer, lover, and unknowing model; and last, she stands next to an image of the aged Picasso – she is as voluptuous and amazonian as she would have seemed to the teenaged version (B1868).

Despite her seeming triviality to the scope of his life, Picasso’s emotional bond to Rosita had persisted, sunken deep into his artful imagination. Perhaps this is simply due to the time of their connection: the beginning of his artistic study, those impressionable teenage years. Regardless, when it came time to commit to paper how he remembered his life, Picasso thought of her. This small figure had left a big mark.

*RICHARDSON, JOHN. A LIFE OF PICASSO, VOLUME 1: 1881 - 1906. RANDOM HOUSE, 1991. (PP. 68)