hen we last left Picasso, he’d switched from quarters with Max Jacob at the Bateau Lavoir, and into a more domestic situation with his girlfriend, Fernande Olivier, and his monkey.

Of course, upscaling the artist’s living quarters did not descale his interests – he began visiting a bar across the street from his new Paris flat, the Taverne de l’Ermitage, not-so-coincidentally also frequented by a girl: an acrobat, a circus performer, and Picasso’s soon-to-be model.* Her lithe figure bent into his increasingly distorted language of forms, and her supposed name appears in the title of an oil-on-canvas work from the time: Mademoiselle Léonie.**

Pablo Picasso: Mademoiselle Léonie, 1910, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 19 11/16 inches

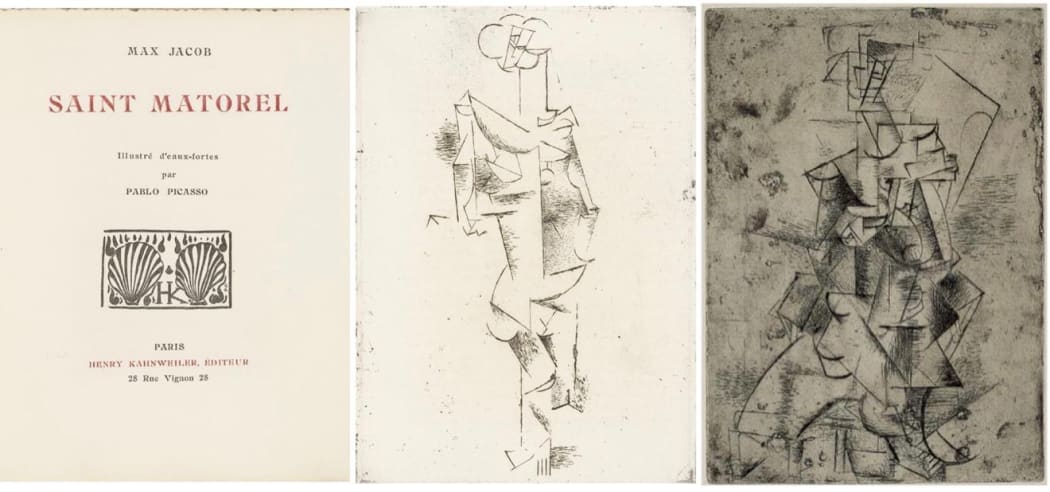

Ladies aside for just a moment – Max Jacob was not to be forgotten. Later in the year of his move, Picasso was approached to do a book illustration: Jacob’s Saint-Matorel. Picasso accepted the opportunity but flagrantly disregarded the idea of illuminating Jacob’s text with his images – rather the opposite, Picasso riffed off the book, creating a series of four small Cubist pictures, some of his only Cubist etchings.*** One sole character from the book actually appears in the etchings, her body acrobatically balanced in two different scenes. And here is where fiction comes to life: she is a prostitute, the protagonist's mistress, and Jacob calls her Mademoiselle Léonie.

Coincidence? Maybe. It could be that Picasso retroactively named the portrait for Jacob’s character; or, Jacob named the character for his friend’s behind-the-scenes behavior. Or: perhaps the combination of the circus performer-and-lover was a motif rooted deeper in the artist’s psyche. Perhaps the composite woman behind the two different Mademoiselle Léonies was not drawn from the Taverne de l’Ermitage nor from Saint-Matorel, but from a memory. More on this next week.