“My ideas,” Edvard Munch wrote in 1926, “developed under the influence of the bohemians or rather under Hans Jaeger. Many people have mistakenly claimed that my ideas were formed under the influence of the Germans . . . but that is wrong. They had already been formed by then.”*

About four decades earlier, Munch had disobeyed his father by dropping out of technical school and enrolling in drawing school. Amongst the artists there, he met Hans Jaeger. Jaeger was not a friend that Munch’s pious father would have chosen. Impotent at twenty by way of syphilis, with his post-Christian philosophy laughed out of university by his mid-twenties, he was half social cast-off and half bohemian philosopher-king, an explosively free thinker. He declared, “I shall not rest until I have corrupted my entire urban generation, or driven them to suicide.”**

Edvard Munch: Hans Jaeger, 1889, oil on canvas, 33.1 X 42.9 inches © Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design

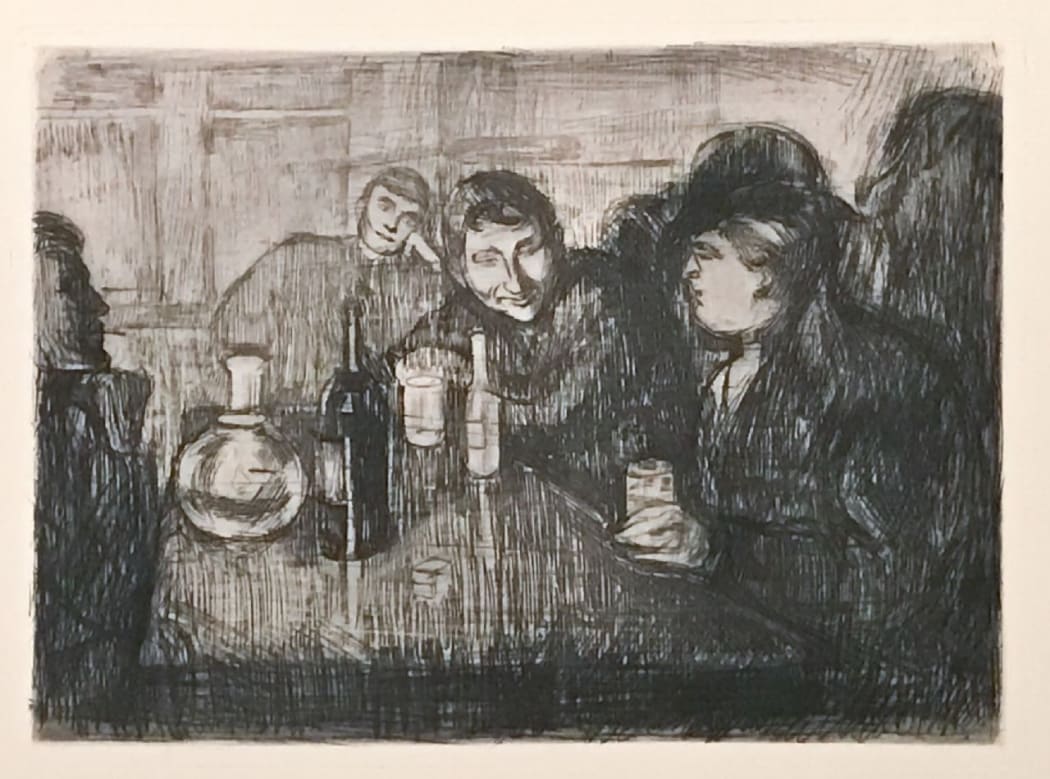

His group of anarchist artists called themselves the Kristiania Bohème. They were tired of being stifled by religion, enforced by their families’ conservative traditions. They replaced walks on the promenade of Karl Johan with long nights drinking in smoky bars, talking philosophy, literature, and art – a scene Munch remembers in Kristiania Bohème I, his first version of the subject. Featured in the background is a reserved, Munch-looking figure, pleasantly observing.

Organized religion had its Ten Commandments; the Kristiania Bohème’s manifesto, recorded on a paper café napkin, pronounced their Nine, including: there is no limit to how badly thou shalt treat thy family and all elders and betters, never borrow less than five kroner, and thou shalt kill thyself.*** They certainly did not include that famous original, “thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife” – but more about that, and the woman at the heartbeat of the Bohème’s gatherings, next week.