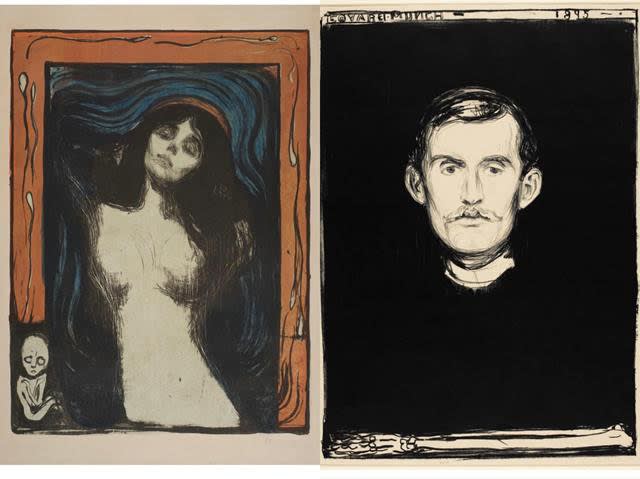

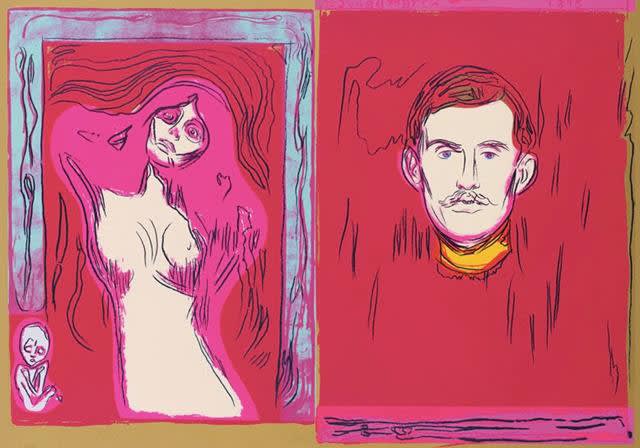

Munch’s Madonna. If you do not know her as one of the artist’s leading ladies, perhaps you’d recognize her languorous pose and wealth of thick dark hair from Andy Warhol’s pinked-out pop art screenprint made after his visit to Oslo in 1984: Madonna & Self-Portrait with Skeleton's Arm (after Munch). As it goes, Warhol’s attention made Munch’s lady an icon. But she had much humbler beginnings – she made her public debut hanging in a prison cell.

Andy Warhol: Madonna & Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm (after Munch), 1984, silkscreen, 32 x 39 15/16 inches.

This story takes place a hundred years before Andy Warhol stepped into the picture, back in Edvard Munch’s formative bohemian days in Kristiania. Hans Jaeger was the leader of the libertine Kristiania Bohème with which Munch spent his time. Jaeger was, foremost, a writer. His characters were sexually liberated women, and his writings advocated for free love. Unfortunately, they didn’t exactly land with his traditional Scandavian audience, and in 1885 he was sentenced to two months in prison because he’d written a novel with a prostitute as the protagonist.

As a going-away present, Munch gifted Jaeger a painting called Hulda – he had crafted the character that had caused so much trouble into wall art. Hulda has since been lost, but she is noted as the early version of the lady herself, Madonna.