-

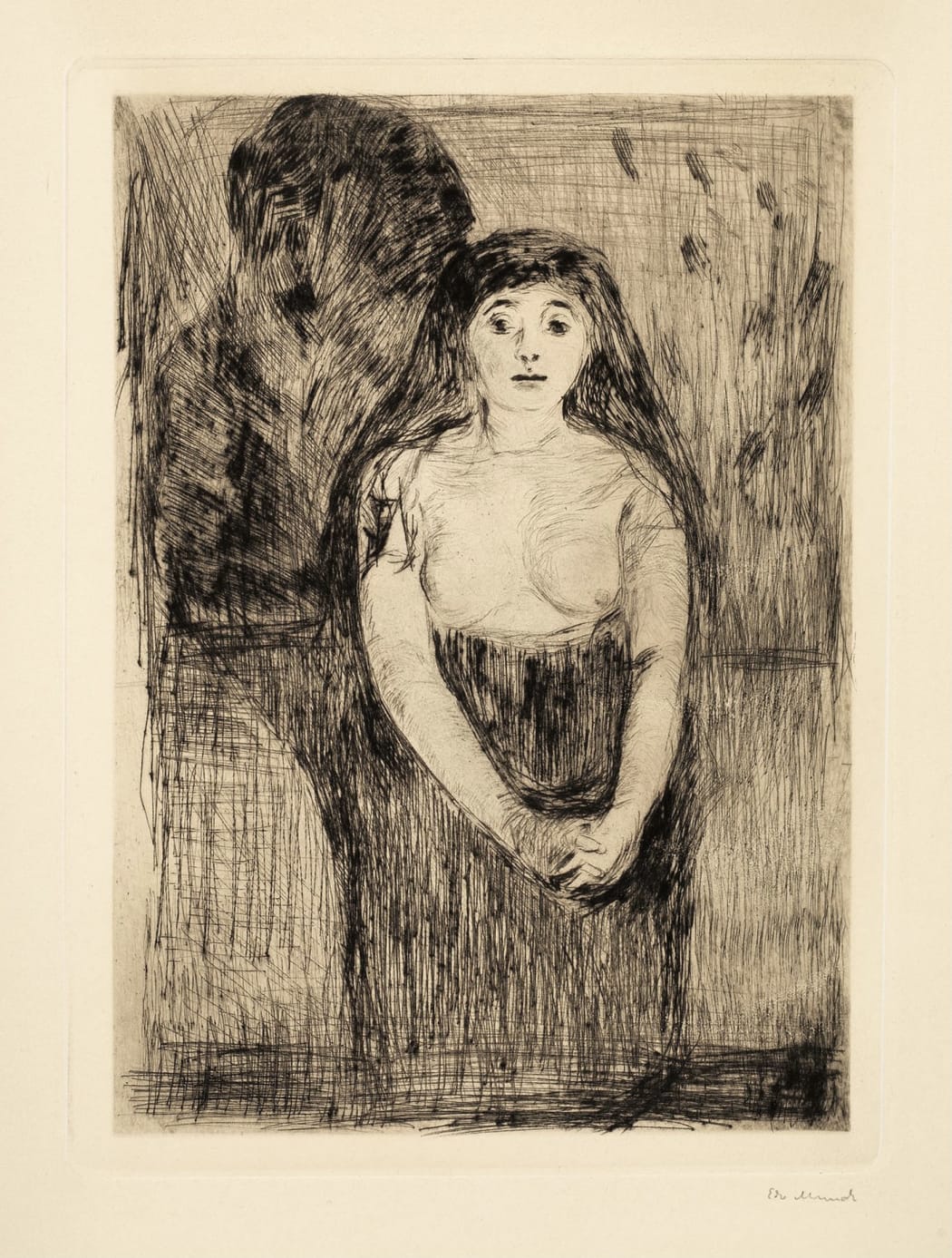

Trøst (Consolation) (Woll 6), 1894, drypoint, 8 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches

Trøst (Consolation) (Woll 6), 1894, drypoint, 8 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches -

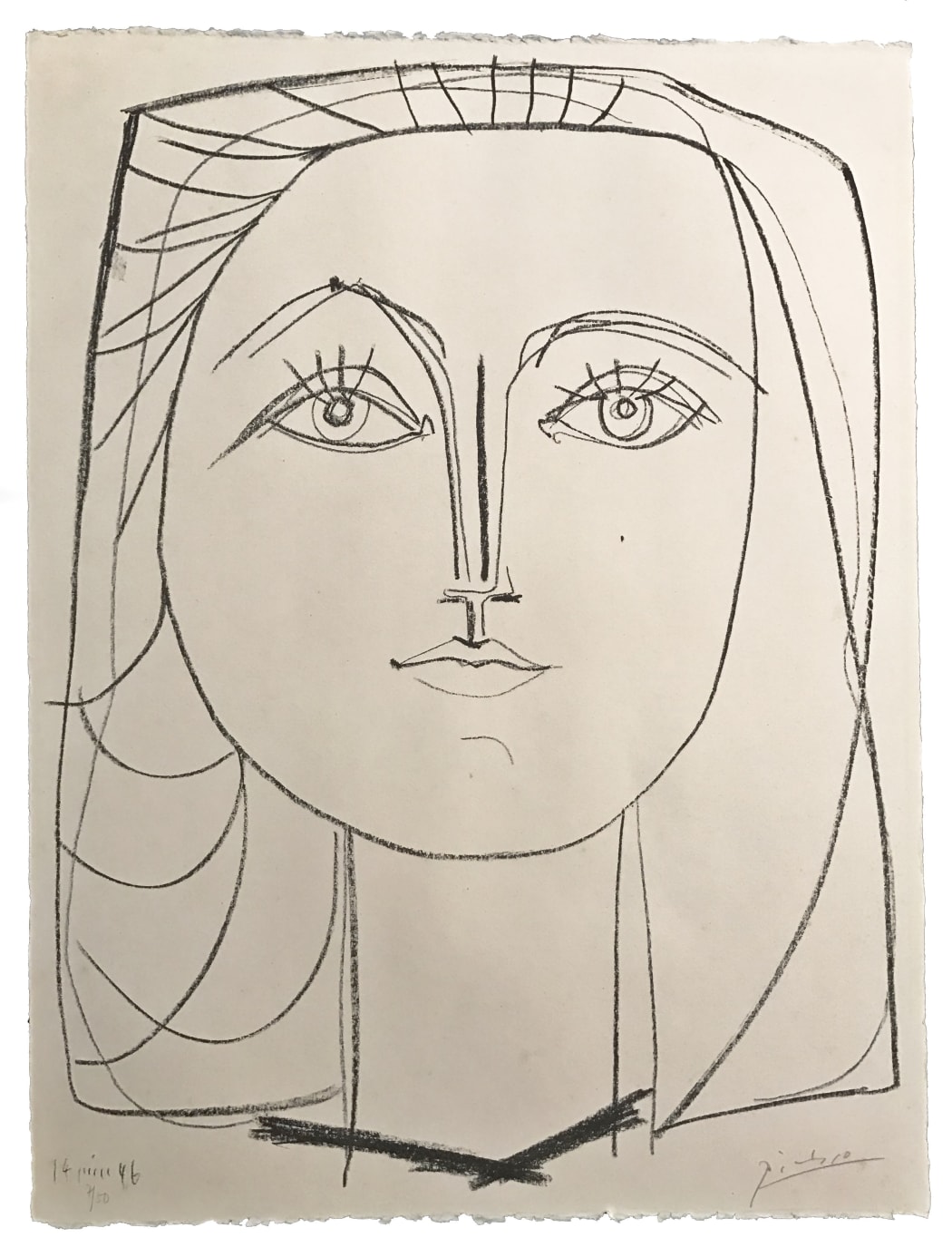

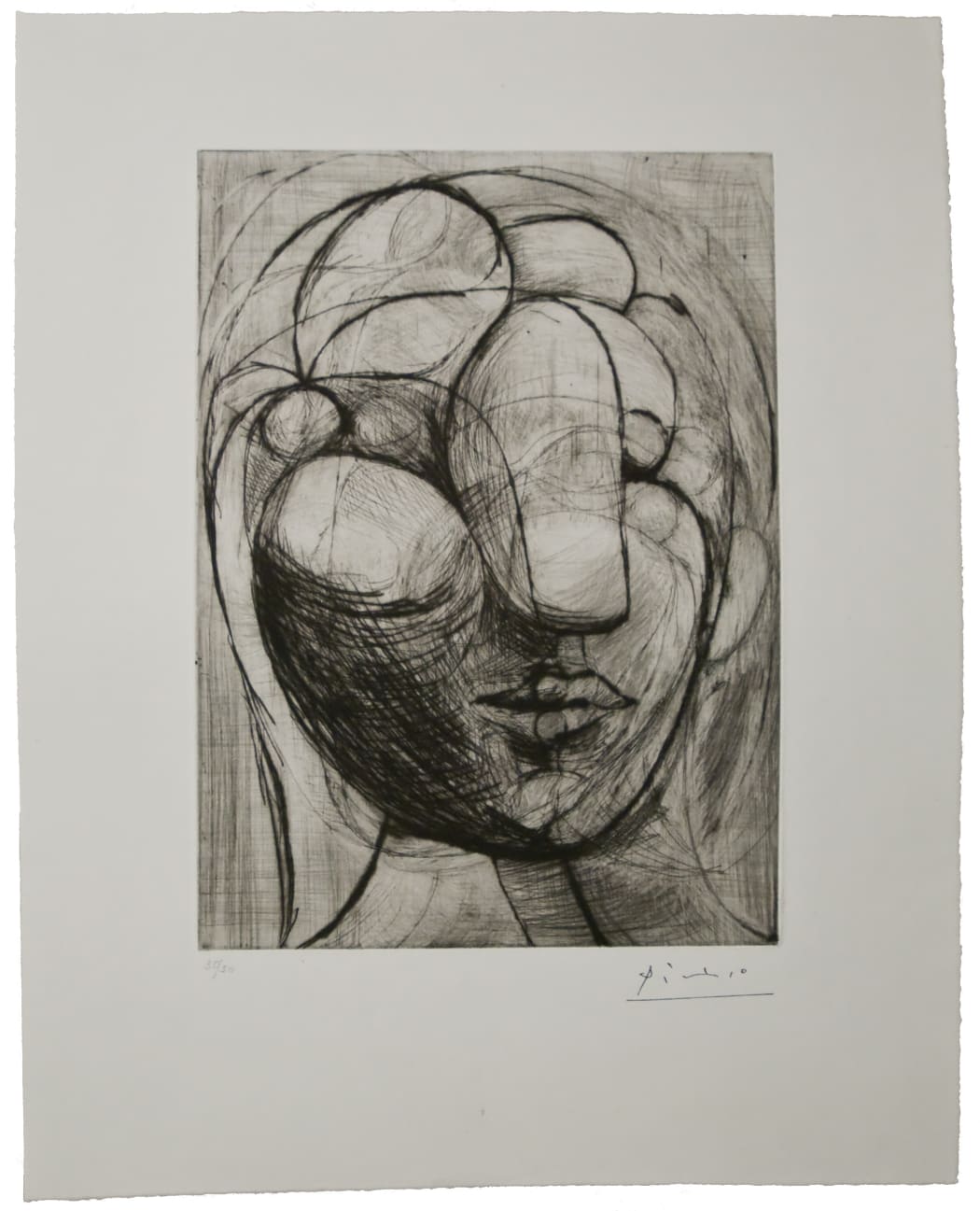

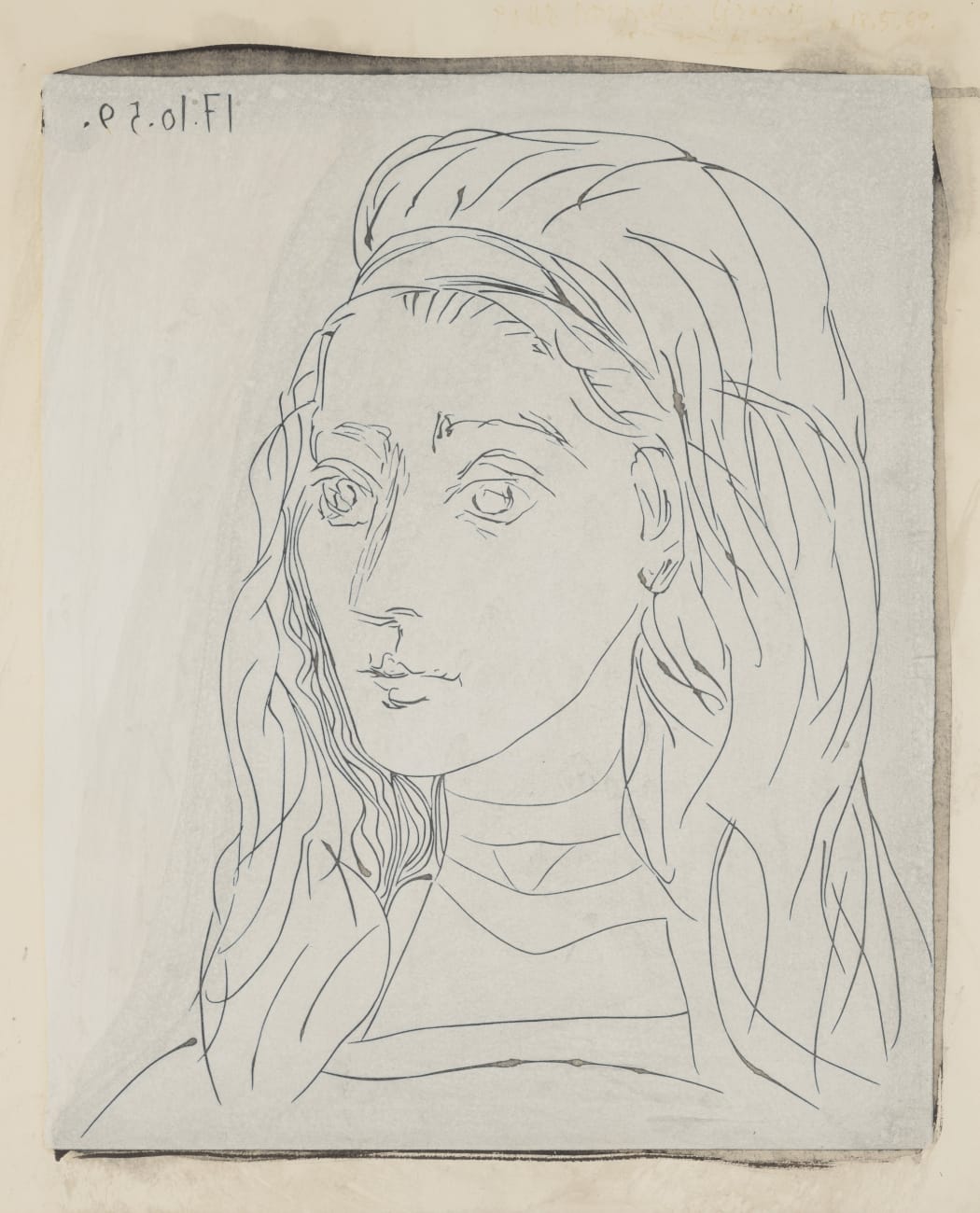

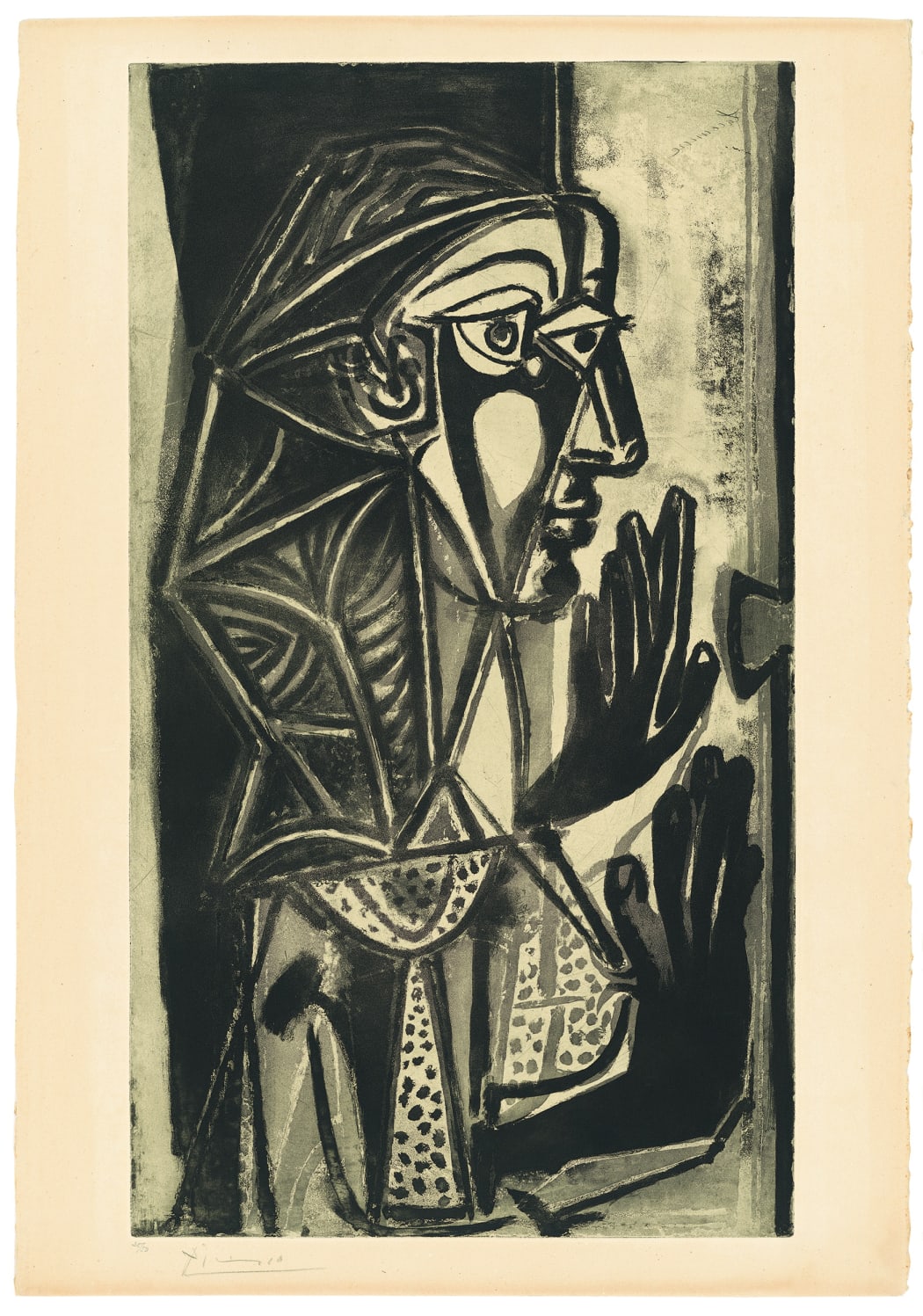

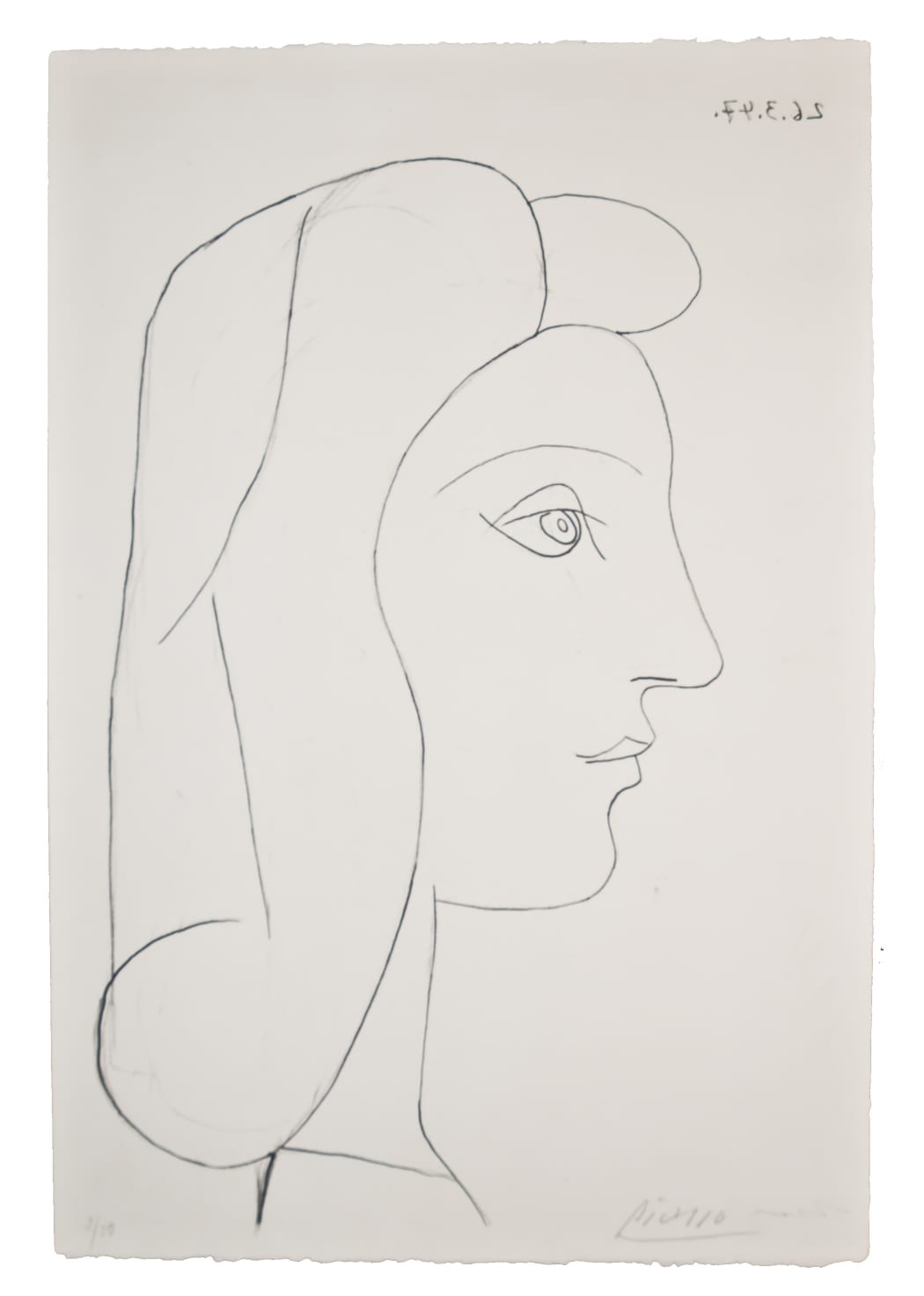

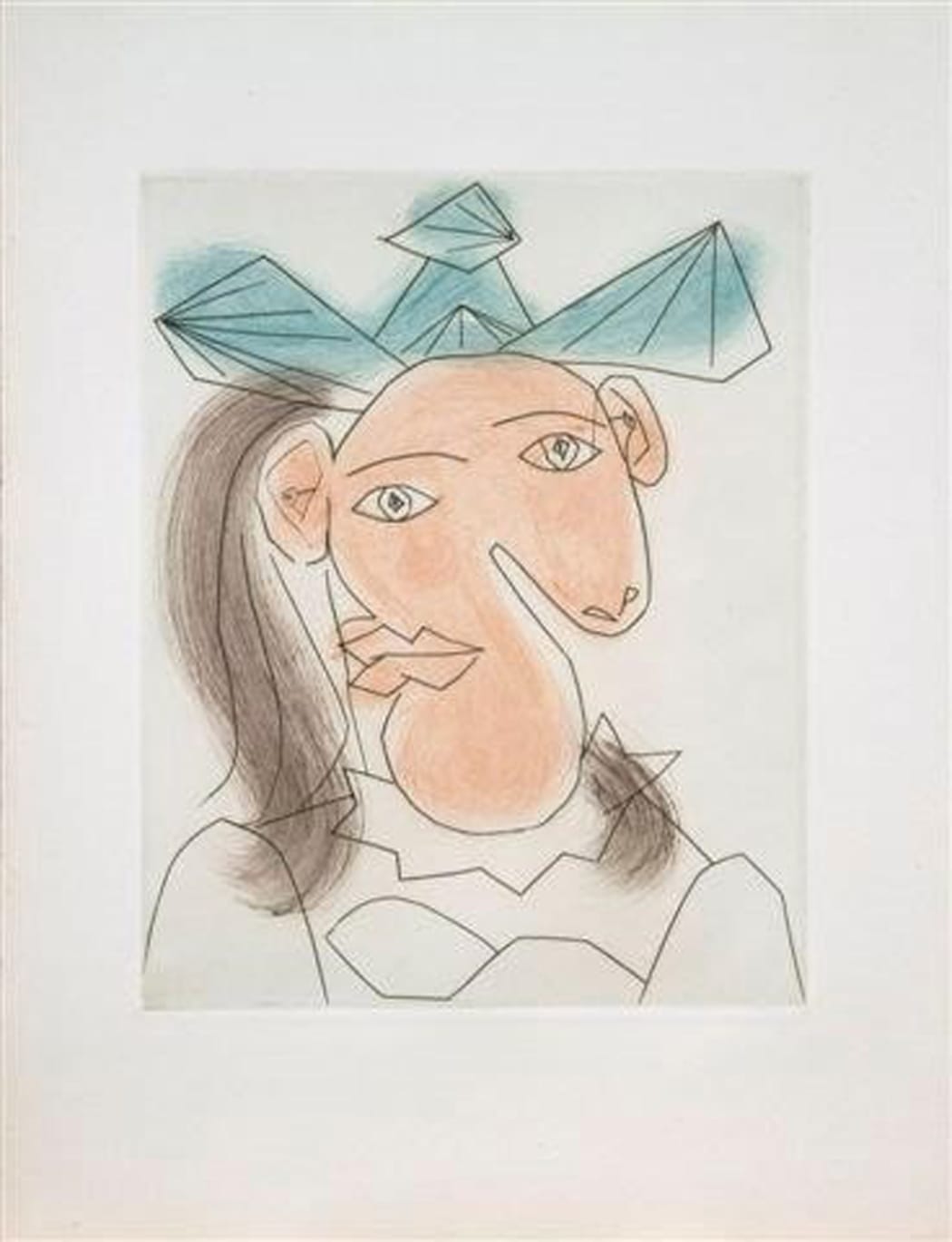

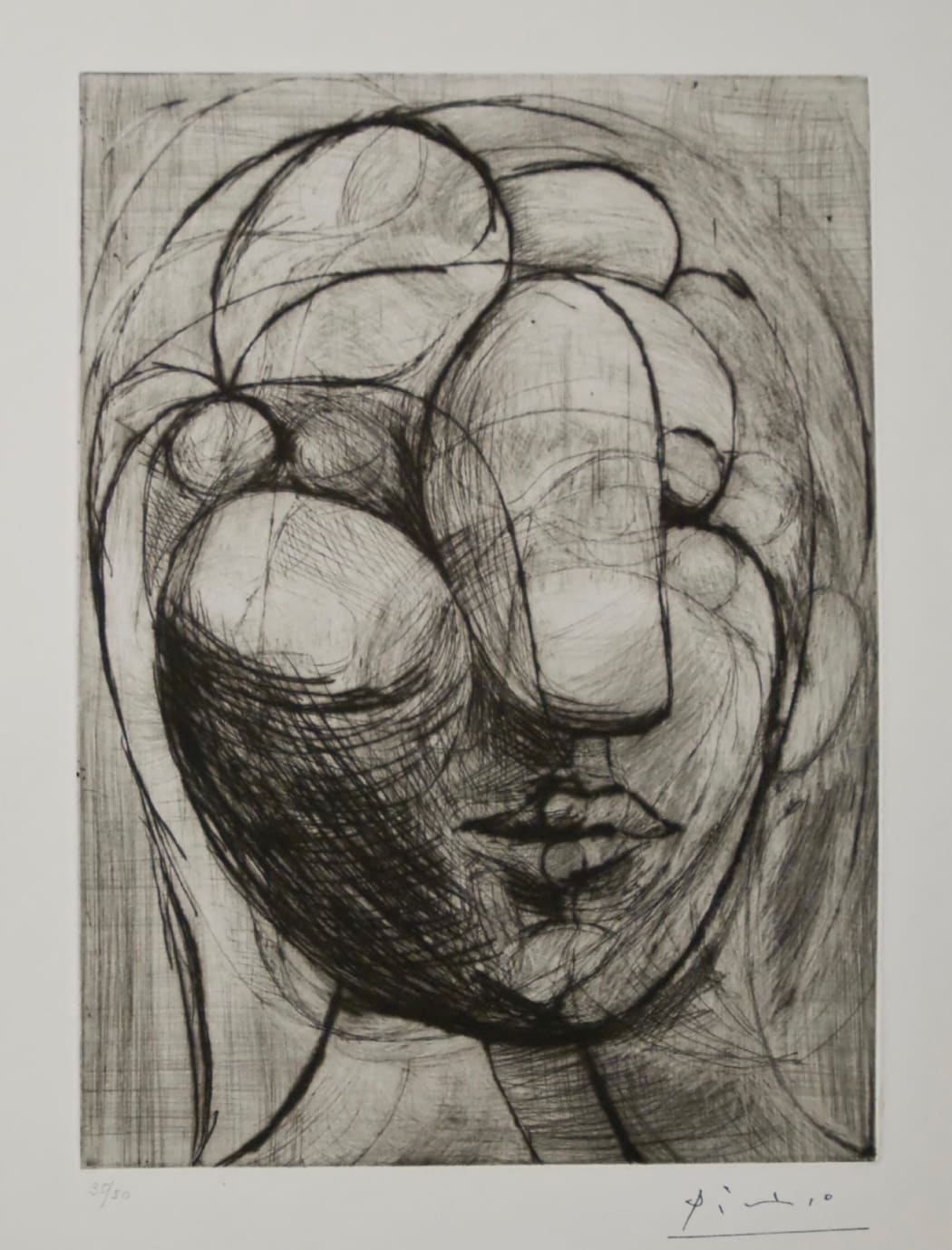

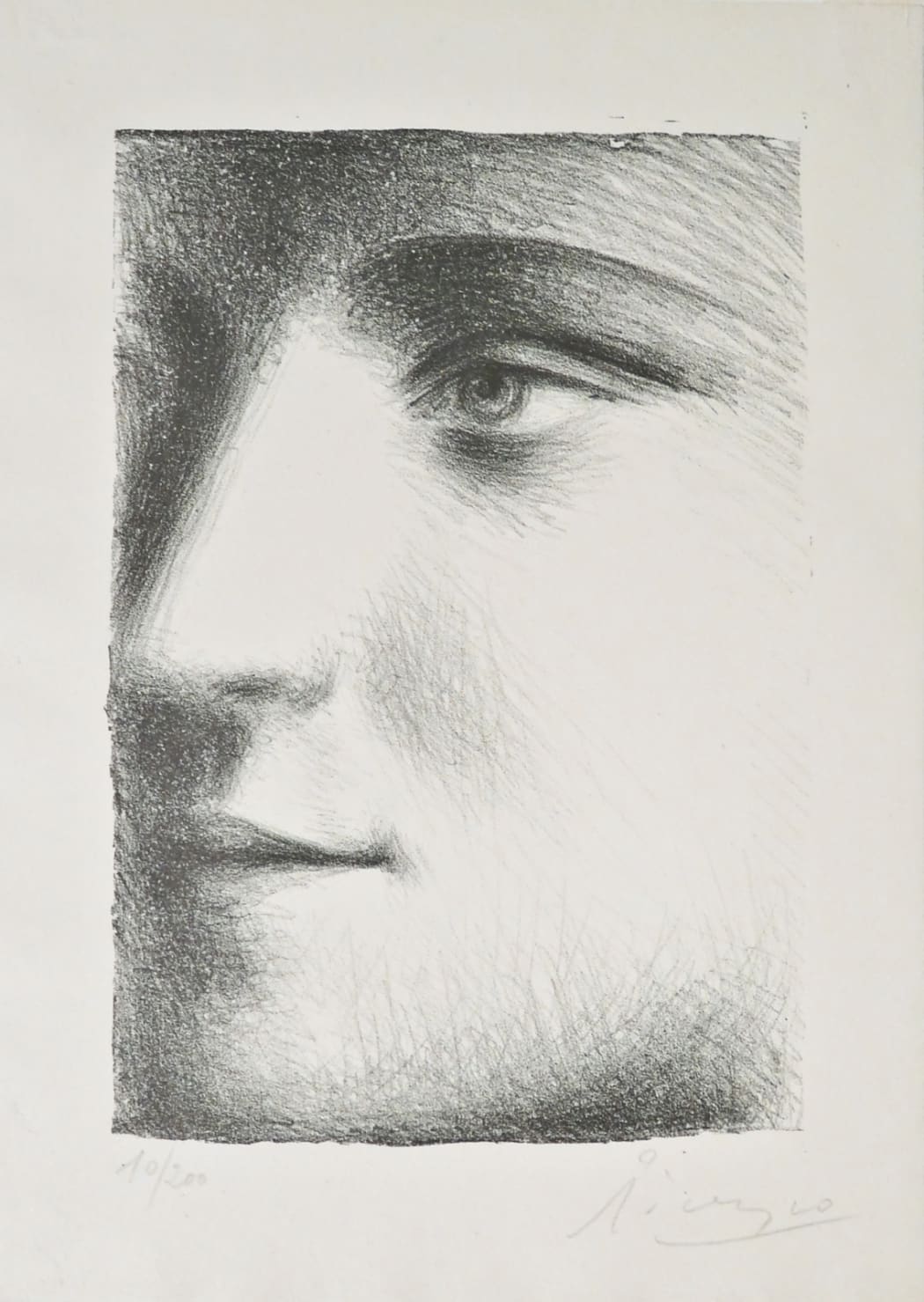

Françoise (Bloch 398), 1946, lithograph, 26 x 19 1/2 inches

Françoise (Bloch 398), 1946, lithograph, 26 x 19 1/2 inches -

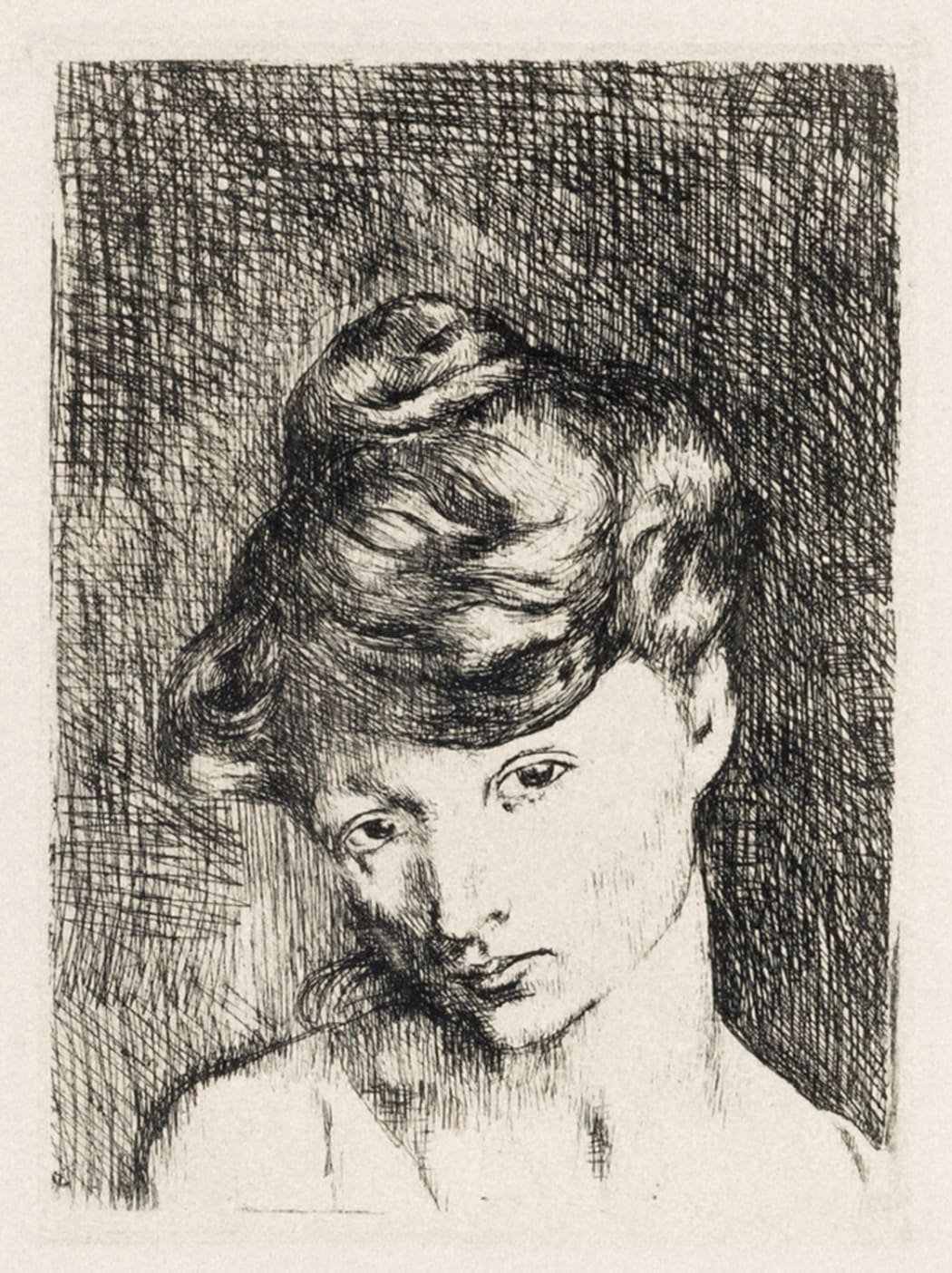

Modellstudie (Study of a Model) (Woll 8) (state II), 1894, drypoint, 11 x 8 1/4 inches

Modellstudie (Study of a Model) (Woll 8) (state II), 1894, drypoint, 11 x 8 1/4 inches -

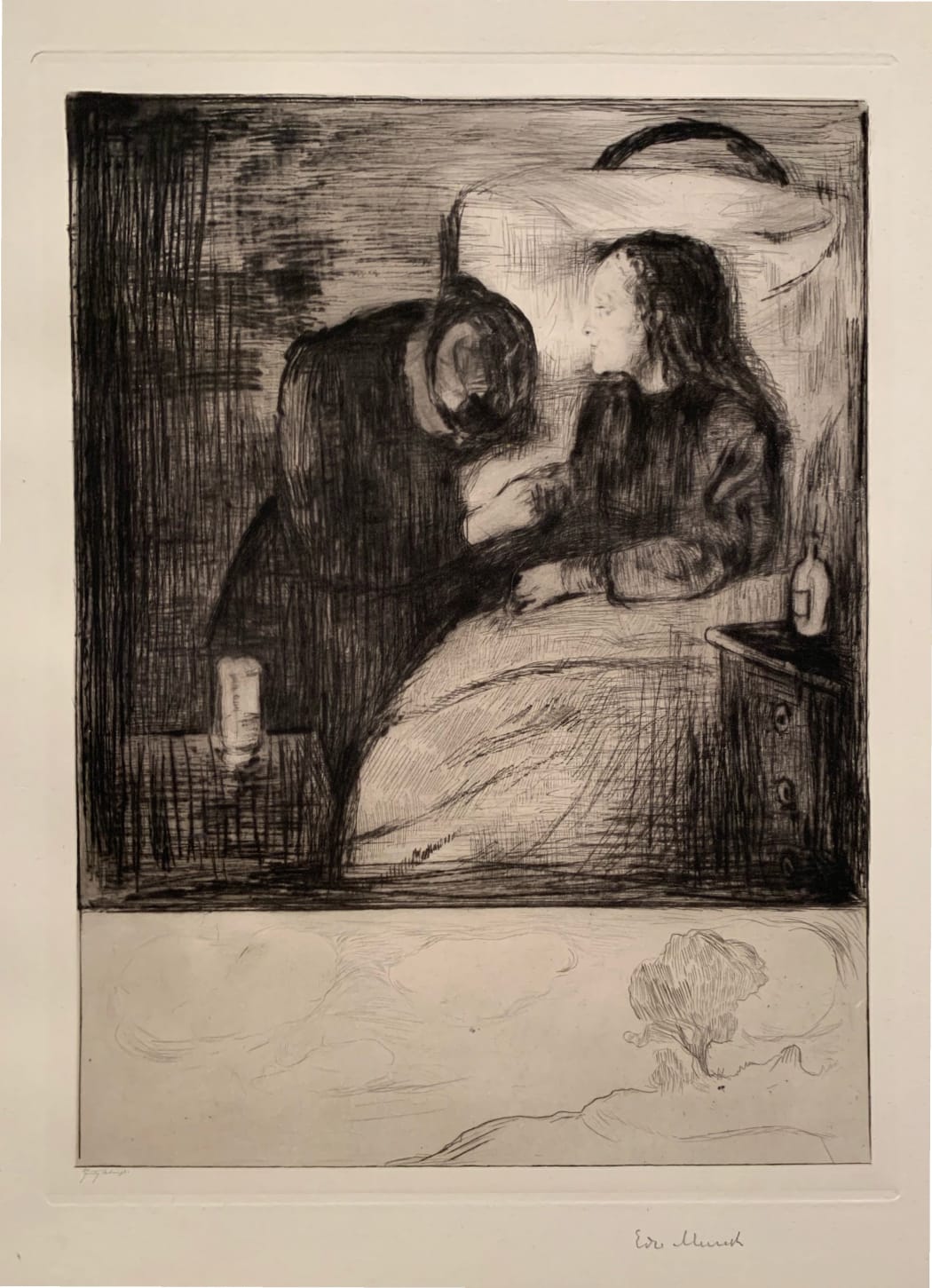

Trøst (Consolation) (Woll 6), 1894, drypoint, 8 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches

Trøst (Consolation) (Woll 6), 1894, drypoint, 8 1/2 x 12 1/2 inchesThese past several weeks we’ve been talking about Picasso’s early days of printmaking. But let's switch gears now. Last month, after over a decade of delays and setbacks, a museum dedicated to Edvard Munch opened in Oslo. Called “MUNCH,” the 13-story building is one of the largest single-artist museums in the world, holding around 28,000 of the artist’s works.

Edvard Munch lived to be 80 years old. To say he left behind quite the legacy would be an understatement. It’s almost too easy though, to image a fate in which his life would have ended much sooner. Marred by a tragic childhood, he fit the bill for the classic “tortured artist.” There’s no doubt he would have been considered a prolific figure in modern art, even if he’d left behind a smaller body of work. But, it just so happens Munch’s first foray into printmaking shares a number of similarities with Picasso’s. And if the artist had never made it to the point where he started to make prints, it’s unclear how renowned he would be today, as prints became a major part of his oeuvre. At the time, it was radical to make art about feelings and the soul. But that was part of Munch’s genius: an innate ability to express emotions, and his willingness to boldly experiment with mediums and techniques in order to find fresh ways to convey his feelings.

Munch didn’t get into printmaking until his early 30s. He had already been working as an artist for a decade yet hadn’t achieved major success from his paintings. He moved to Berlin in 1892, as Kristiania wasn’t much of a cultural hub at the time. Just as Picasso struggled financially when he first moved to Paris, Munch’s early days in Berlin were spent poor and hungry.*

Things started to change after Munch put on a small show of his paintings. His work was deemed inappropriate though, and the show was shut down after only a week. A week, however, turned out to be long enough to put him on the map with Berlin’s avant-garde. As his popularity grew, Munch wanted his work to reach a larger number of people— a quest that led him to discover printmaking, and all it had to offer.

Unlike Picasso, though— whose use of the new medium coincided with his use of new subjects and a transition from his blue period to his rose period— Munch didn’t shake his angst and isolation. Instead, he utilized printmaking techniques to rework his motifs and express the emotional atmosphere in new ways.

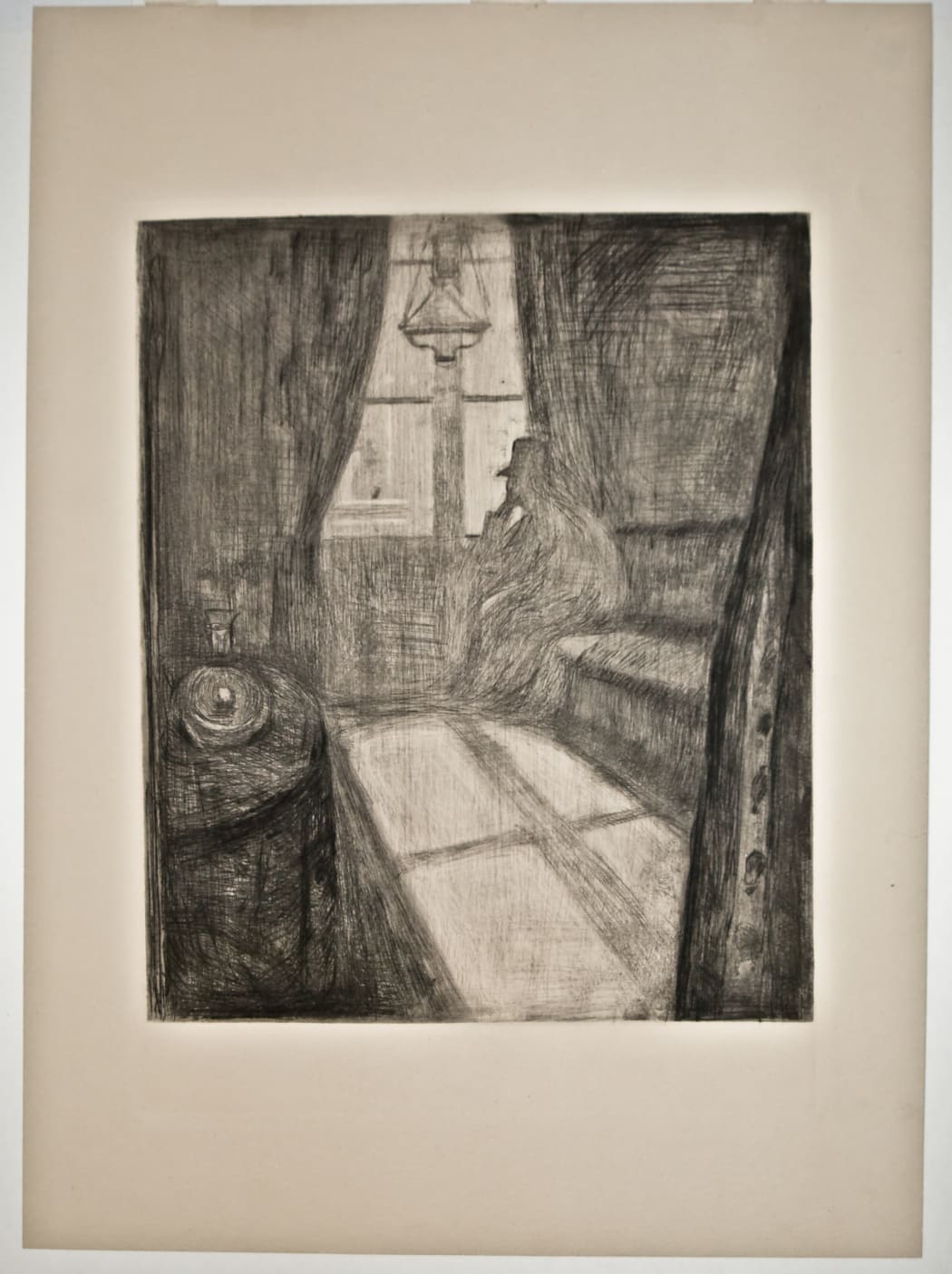

Trost (Consolation) (W6), a drypoint created in 1894, is a good example of this. Dark shading connects the two lovers to each other, but a distinct line still separates them. While the man is mostly surrounded by light, a dark figure looms over the woman. And just like that, we experience that raw human element; the delicate gloom that exists in so many of Munch’s depictions of love and relationship.** This theme of consolation is one Munch would keep coming back to, a man embracing a woman amidst anguish. The melancholia of these images is unsettling, but the title suggests something more revealing. Consoling is, after all, to alleviate a sense of loss or grief. There is even the notion of consolation as medical intervention; the concept that "Before and after fundamental medicine offers diagnoses, drugs, and surgery to those who suffer, it should offer consolation” and “This comfort may be one person's promise not to abandon another. Consolation may render loss more bearable by inviting some shift in belief about the point of living a life that includes suffering. Thus consolation implies a period of transition: a preparation for a time when the present suffering will have turned.”***

Thinking about consolation alongside the personal grief that fueled the artist’s art, is it possible that even in his darkest moments of despair, he could find an element of human comfort somewhere inside? Could it even be part of the reason he was able to make it through, living his life into old age? Munch said himself, “Naturalism, Impressionism, Symbolism are movements that have become means of expressing a single concern, the human.”

Printmaking was the medium that allowed Munch to distribute his work to the widest audience; work that expressed his sorrow, his fear, his joy, his pain… in essence, his humanity. A humanity that spoke to the people, because they shared in and related to it. And they continue to feel connected to those works today. Enough so to fill a 13 story museum with them.* The radical prints of Edvard Munch: 'new ways to express moods and emotions.’ The prints of Edvard Munch | Christie's. April, 9, 2019.

** Prelinger, Elizabeth, et al. The Symbolist Prints of Edvard Munch: The Vivian and David Campbell Collection. Yale University Press, 1996.

*** Arthur W. Frank, The Renewal of Generosity: Illness, Medicine, and How to Live. University of Chicago Press, 2009. -

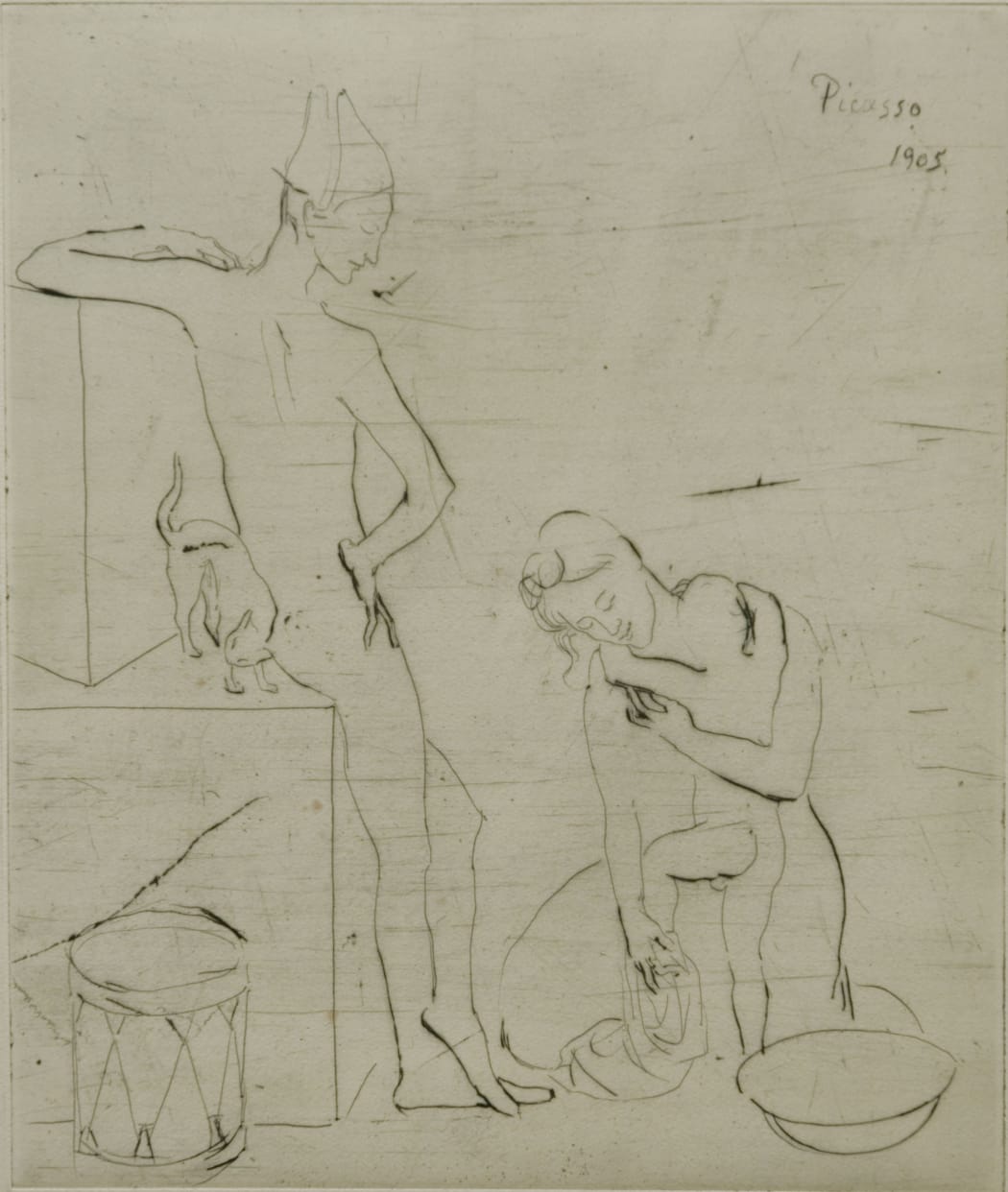

Le Saltimbanque au Repos (Bloch 10), 1905, drypoint, 4 3/4 x 3 7/16 inches

Le Saltimbanque au Repos (Bloch 10), 1905, drypoint, 4 3/4 x 3 7/16 inches -

Tête de Femme: Madeleine (Bloch 2), 1905, etching, 4 3/4 x 3 1/2 inches

Tête de Femme: Madeleine (Bloch 2), 1905, etching, 4 3/4 x 3 1/2 inches -

Salomé (Bloch 14), 1905, drypoint, 15 7/8 x 13 3/4 inches

Salomé (Bloch 14), 1905, drypoint, 15 7/8 x 13 3/4 inches -

Le Bain (Bloch 12), 1905, drypoint,13 1/2 x 11 3/8 inches

Le Bain (Bloch 12), 1905, drypoint,13 1/2 x 11 3/8 inches -

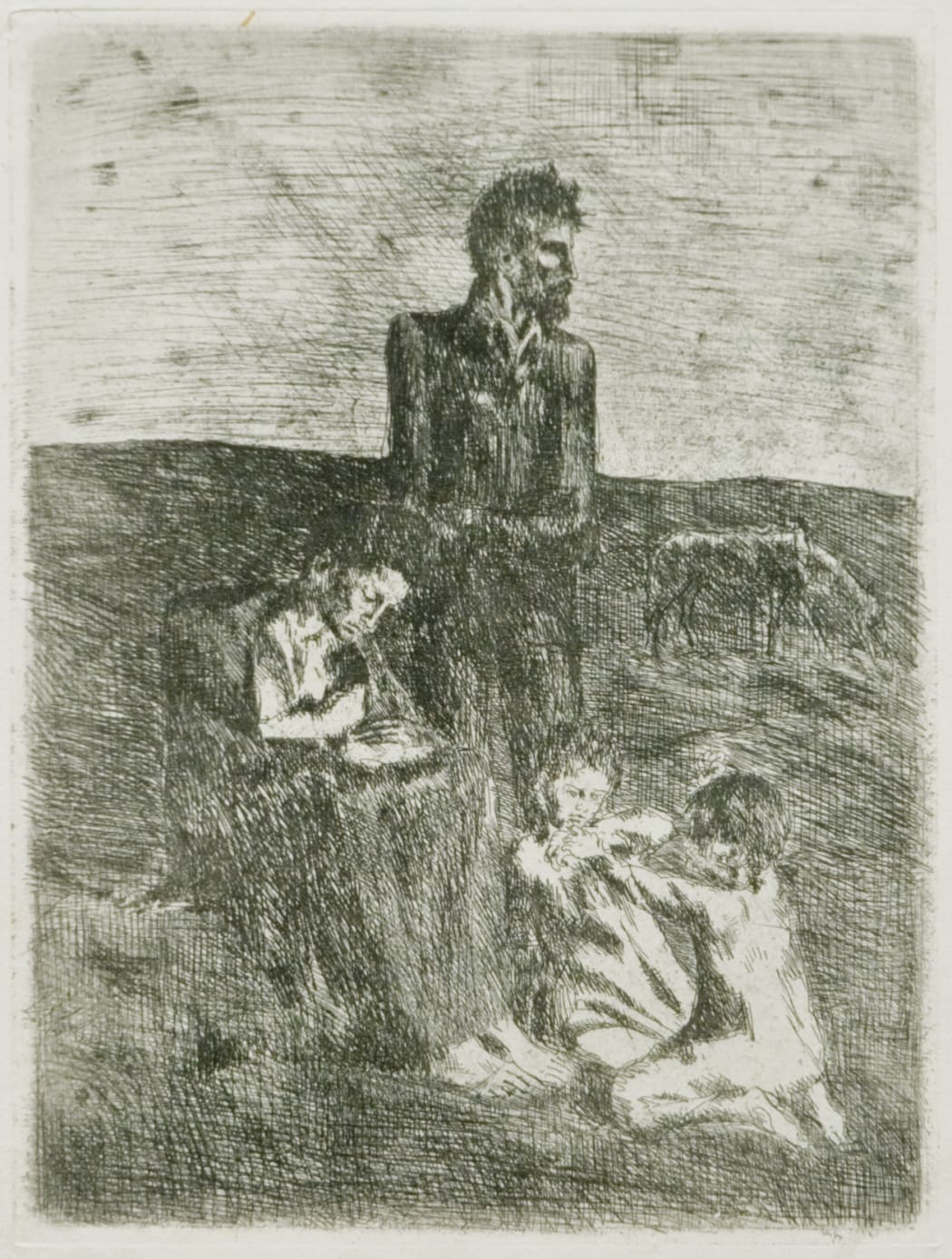

Les Pauvres (Bloch 3), 1905, Etching, 9 1/4 x 7 inches

Les Pauvres (Bloch 3), 1905, Etching, 9 1/4 x 7 inches -

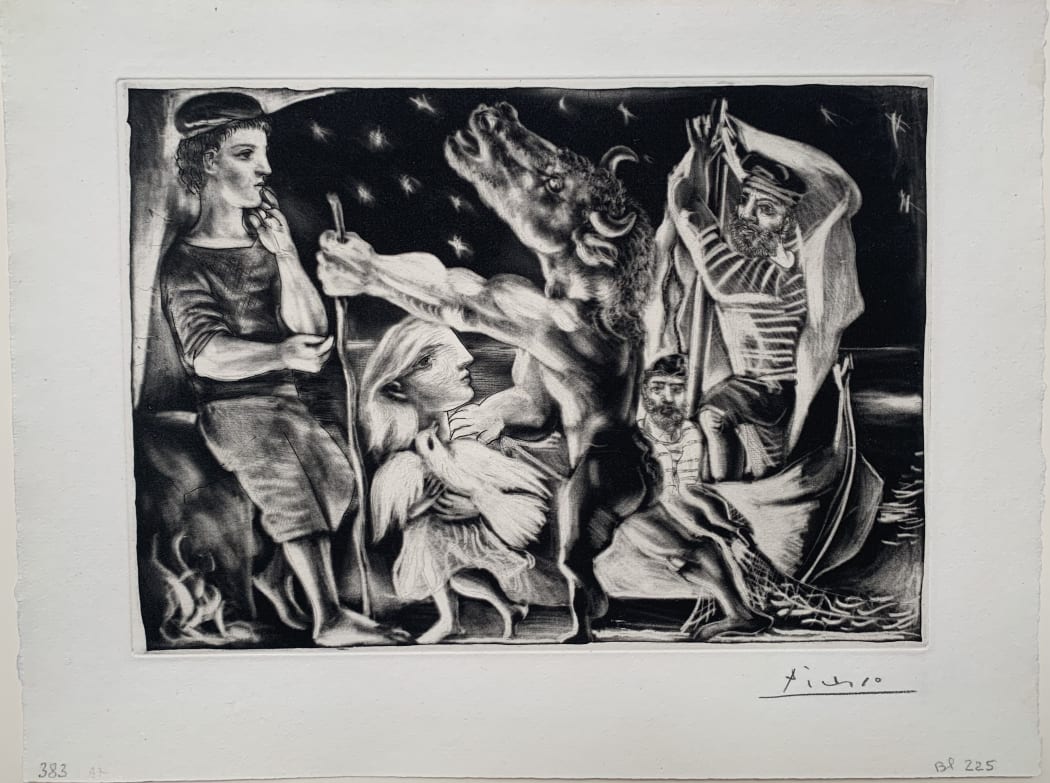

Minotaure aveugle guidé par Marie-Thérèse au Pigeon dans une Nuit étoilée (S.V. 97) (Bloch 225), 1934, Aquatint, scraper, drypoint and burin, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches

Minotaure aveugle guidé par Marie-Thérèse au Pigeon dans une Nuit étoilée (S.V. 97) (Bloch 225), 1934, Aquatint, scraper, drypoint and burin, 9 3/4 x 13 3/4 inches -

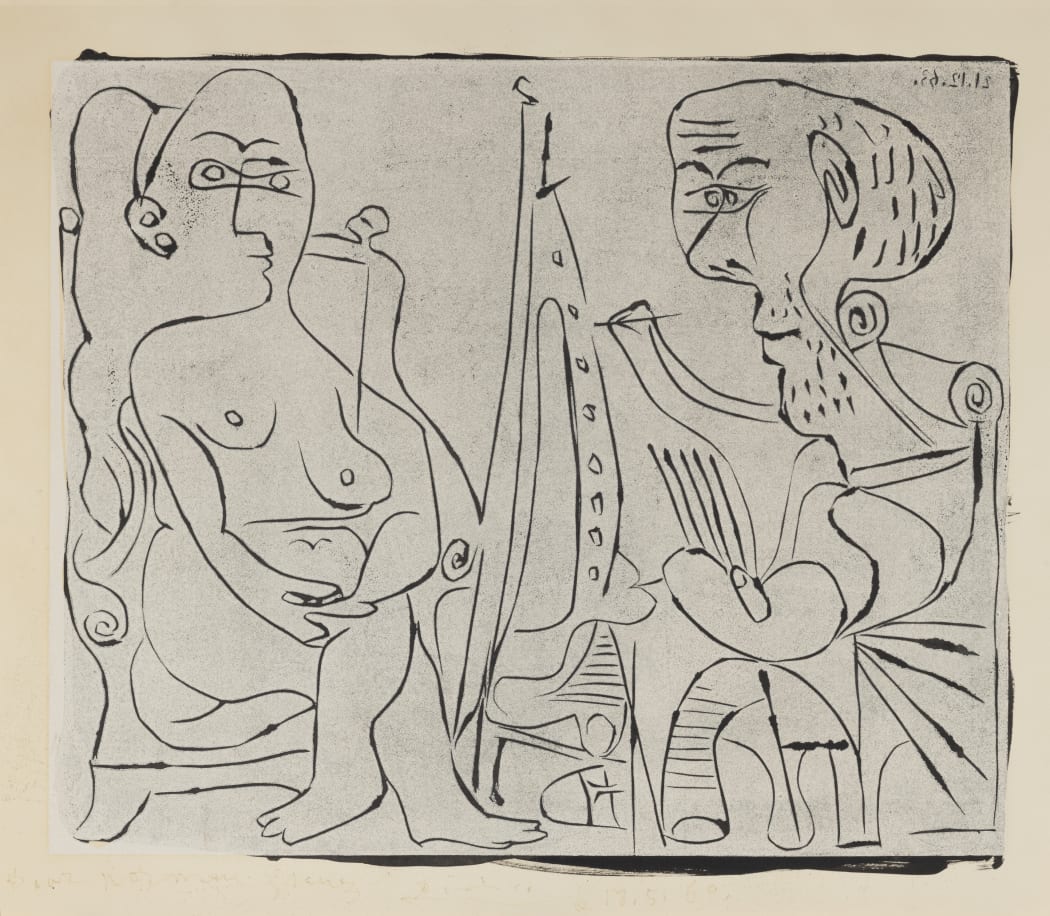

Peintre et modèle au fauteuil (Baer 1347), 1963, linocut rincé, 20 7/8 x 25 1/4 inches

Peintre et modèle au fauteuil (Baer 1347), 1963, linocut rincé, 20 7/8 x 25 1/4 inches -

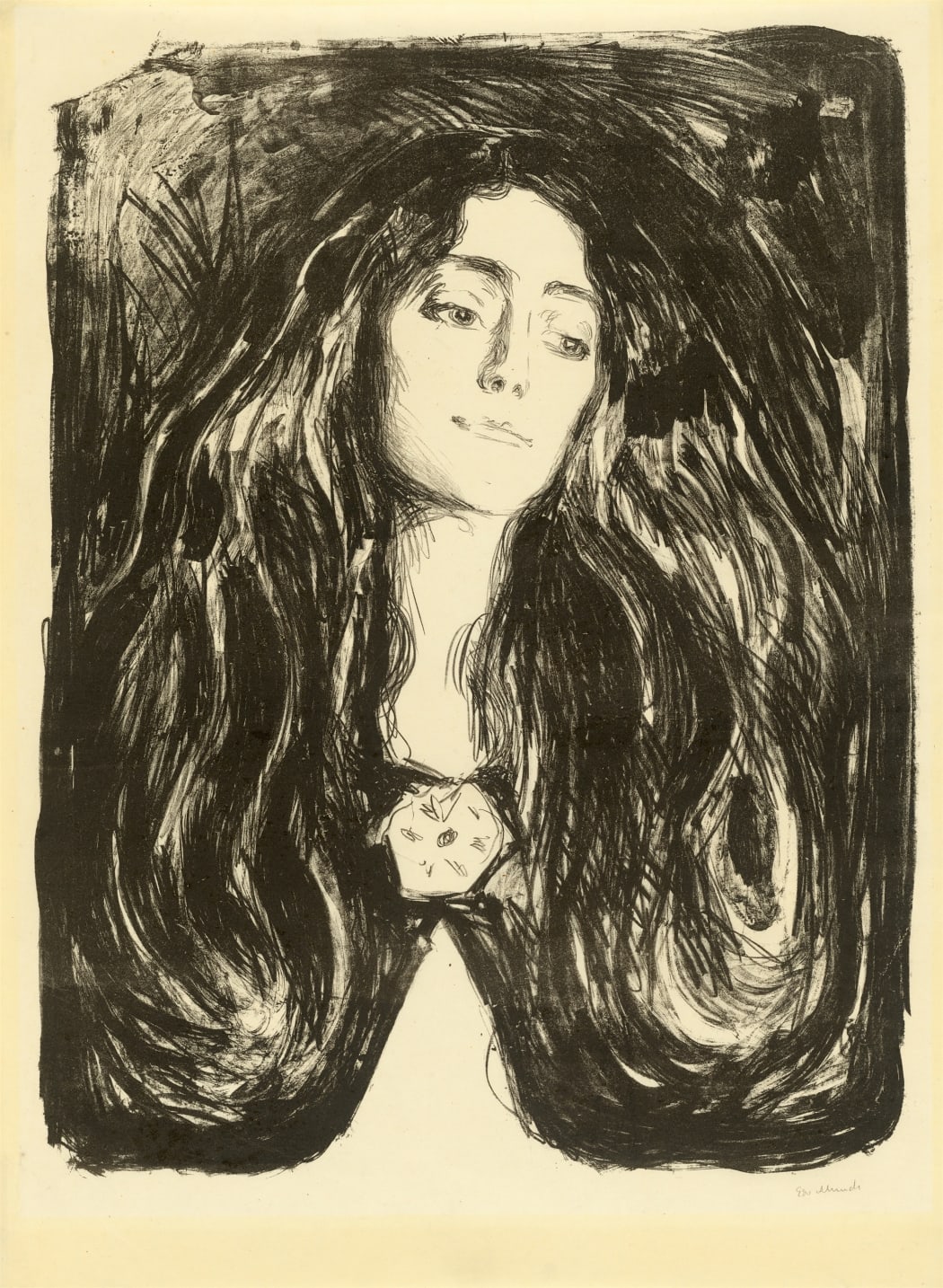

Die Brosche. Eva Mudocci (Woll 244) , 1903, lithograph, 23 7/8 x 18 3/8 inches

Die Brosche. Eva Mudocci (Woll 244) , 1903, lithograph, 23 7/8 x 18 3/8 inches -

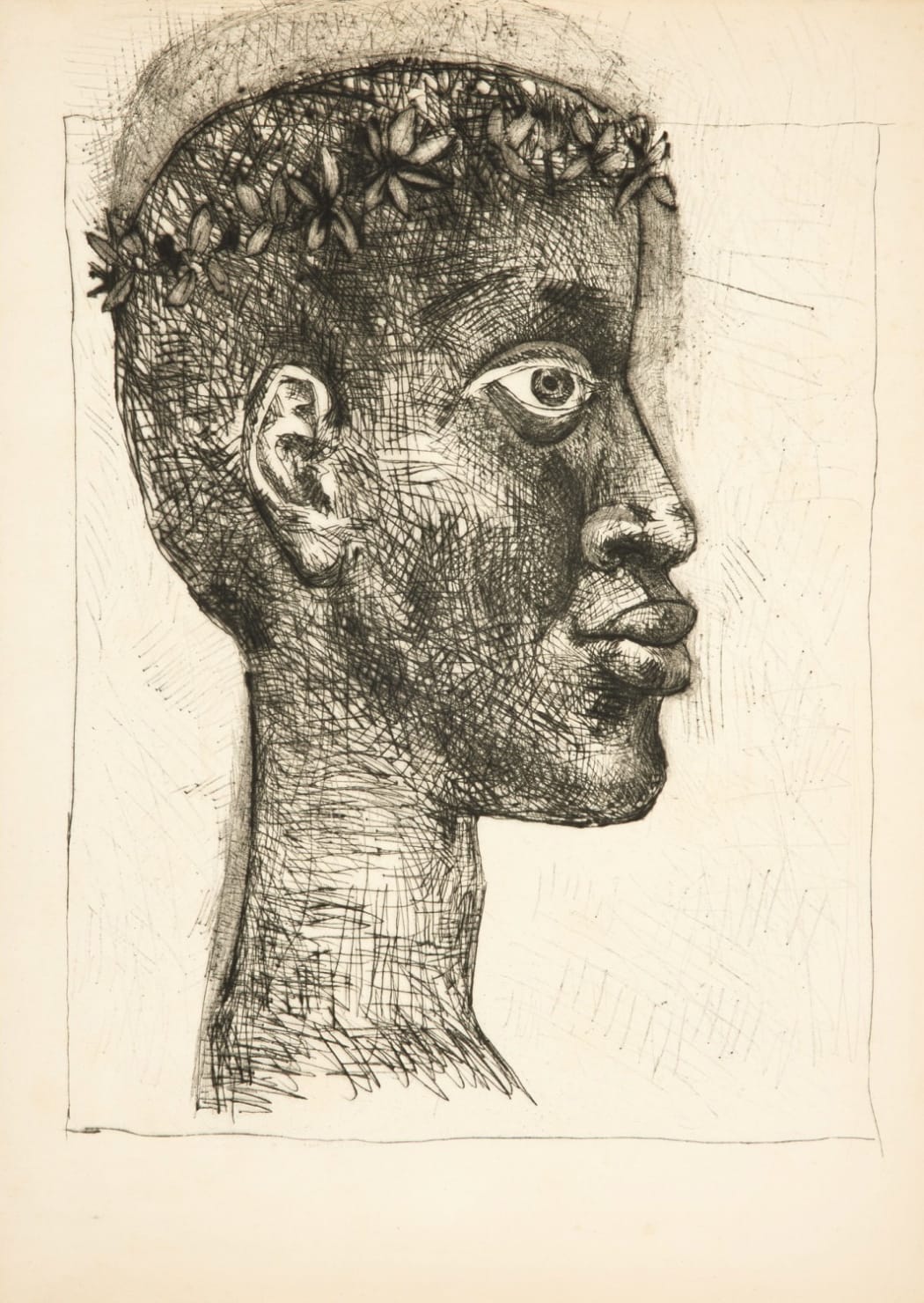

Nègre (Bloch 633), 1949, drypoint, 15 1/2 x 11 inches

Nègre (Bloch 633), 1949, drypoint, 15 1/2 x 11 inches -

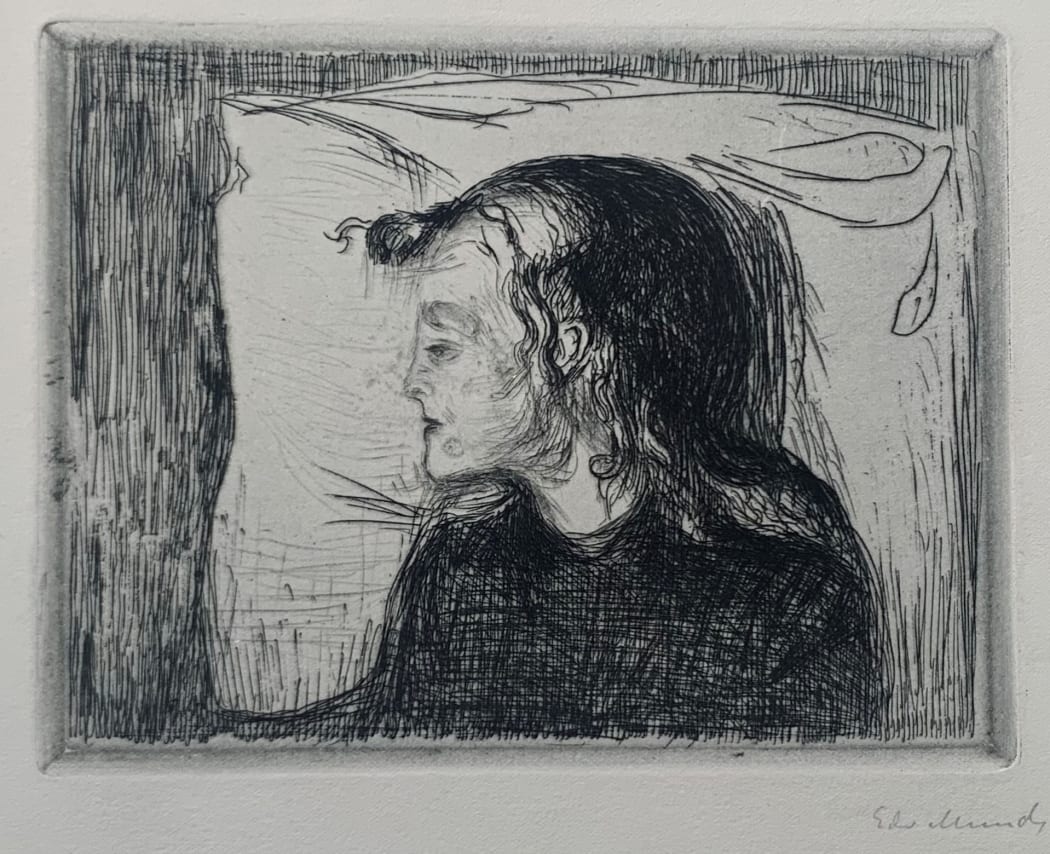

Det syke bar (The sick child) (Woll 59), 1896, etching, 5 7/16 x 7 3/16 inches

Det syke bar (The sick child) (Woll 59), 1896, etching, 5 7/16 x 7 3/16 inches -

Sculpture. Tête de Marie-Thérèse (Bloch 250), 1933, Drypoint and scraper, 12 1/2 x 9 inches

Sculpture. Tête de Marie-Thérèse (Bloch 250), 1933, Drypoint and scraper, 12 1/2 x 9 inches -

Das Kranke Kind (The Sick Child) (Woll 7), 1894, drypoint, 15 x 11 1/4 inches

Das Kranke Kind (The Sick Child) (Woll 7), 1894, drypoint, 15 x 11 1/4 inches -

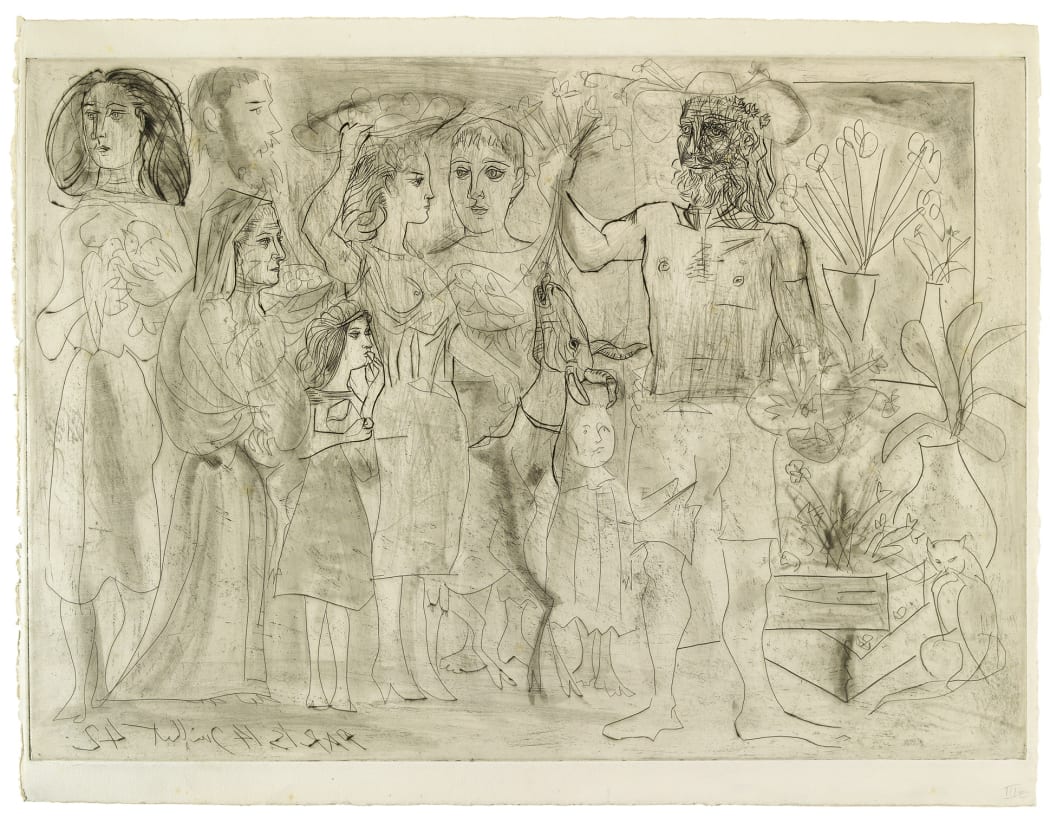

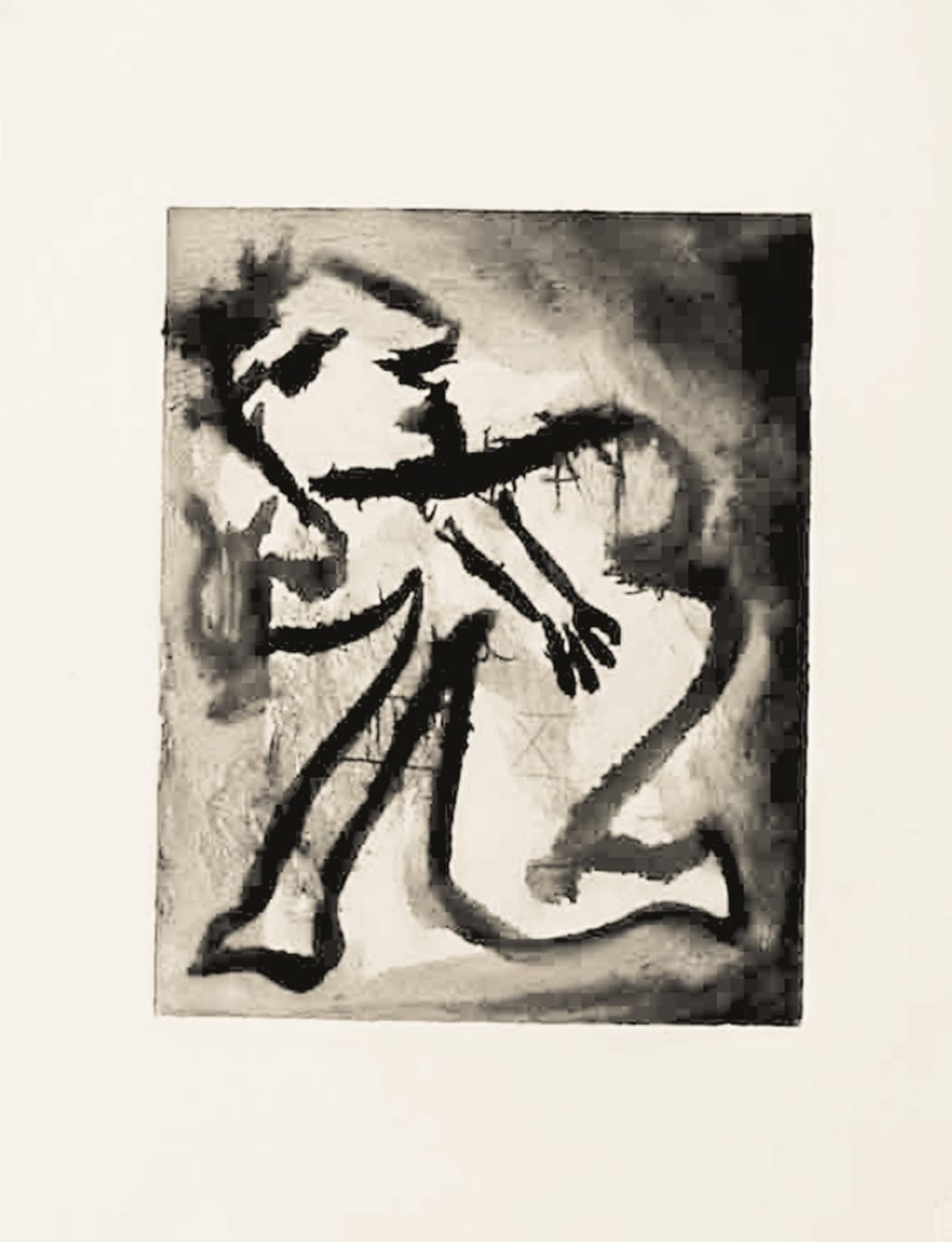

Paris, 14 Juillet 42 (Baer 682), 1942, etching, 17 1/2 x 25 1/4 inches

Paris, 14 Juillet 42 (Baer 682), 1942, etching, 17 1/2 x 25 1/4 inches -

Måneskinn. Natt i Saint-Cloud (Moonlight. Night in Saint-Cloud) (Woll 17)), 1895, drypoint, 17 1/2 x 12 7/8 inches

Måneskinn. Natt i Saint-Cloud (Moonlight. Night in Saint-Cloud) (Woll 17)), 1895, drypoint, 17 1/2 x 12 7/8 inches -

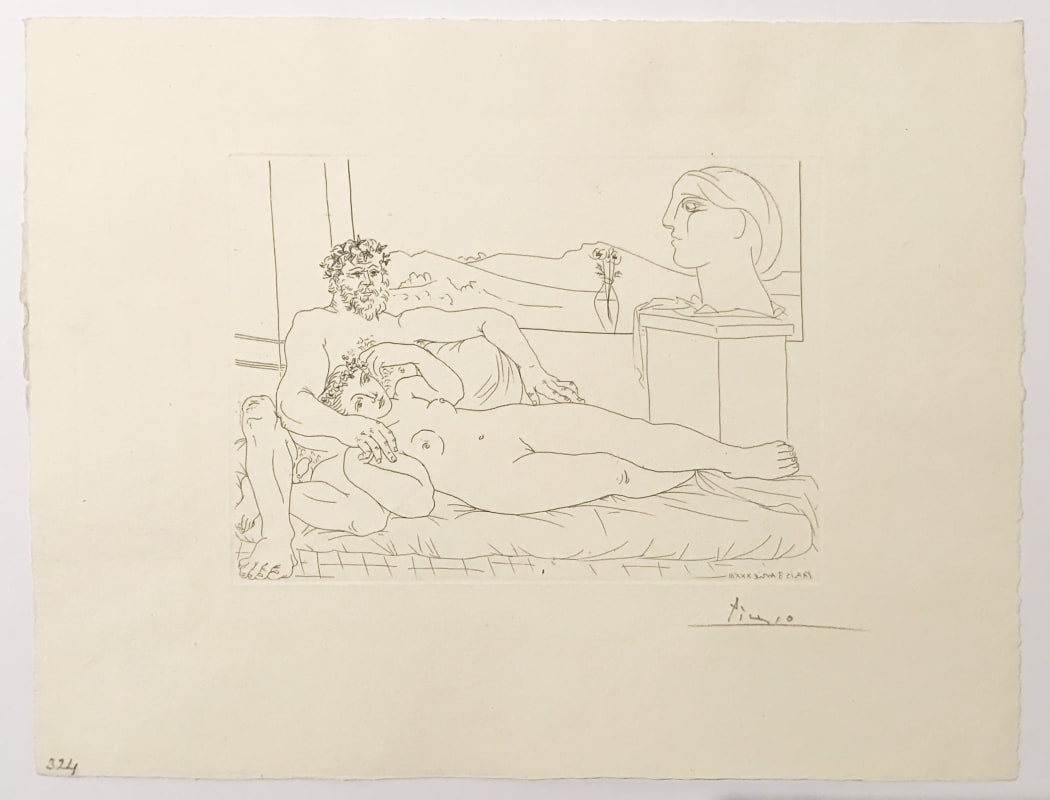

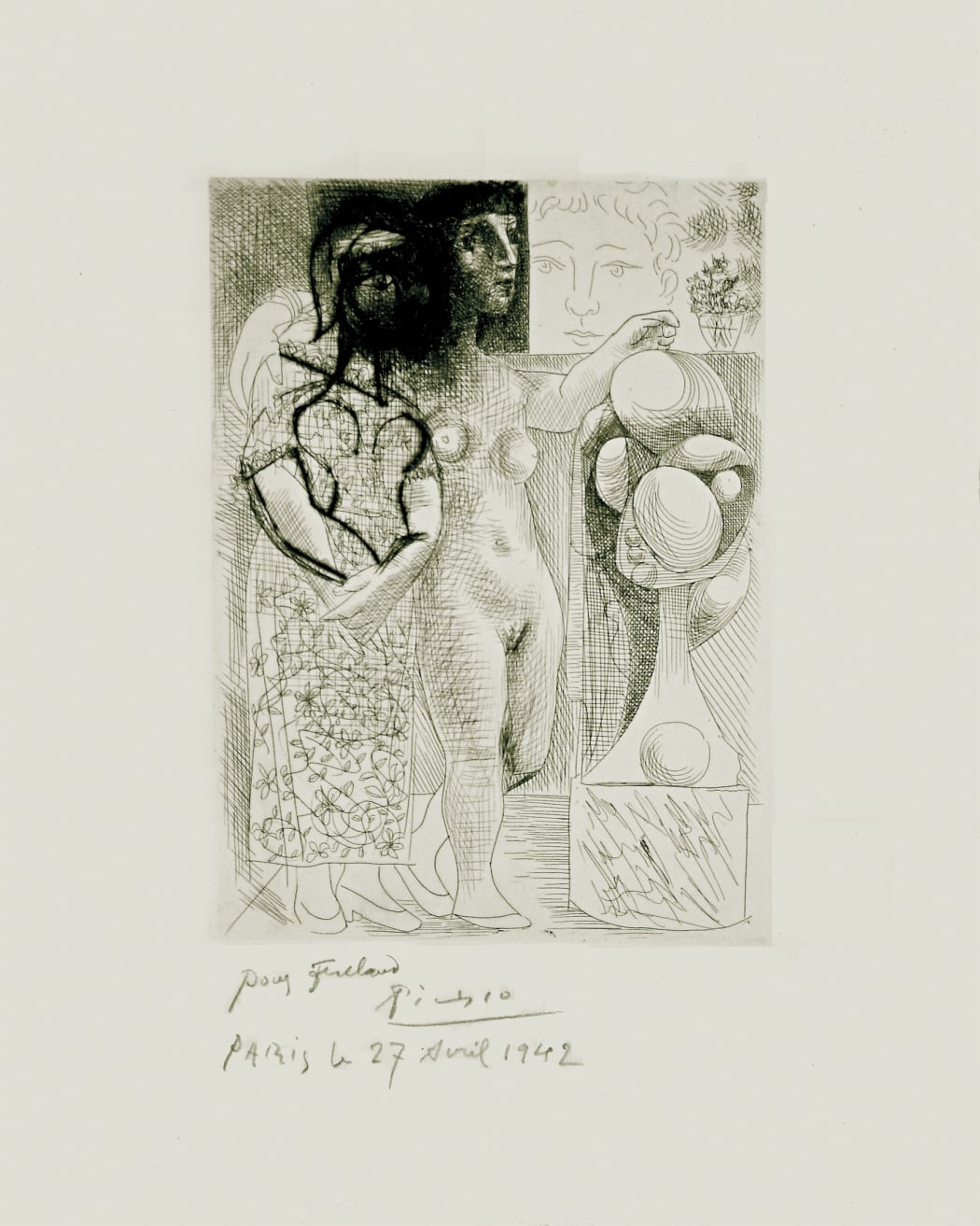

Vieux Sculpteur et Jeune Modèle avec le Portrait sculpté du Modèle (S.V. 63) (Bloch 172), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches

Vieux Sculpteur et Jeune Modèle avec le Portrait sculpté du Modèle (S.V. 63) (Bloch 172), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches -

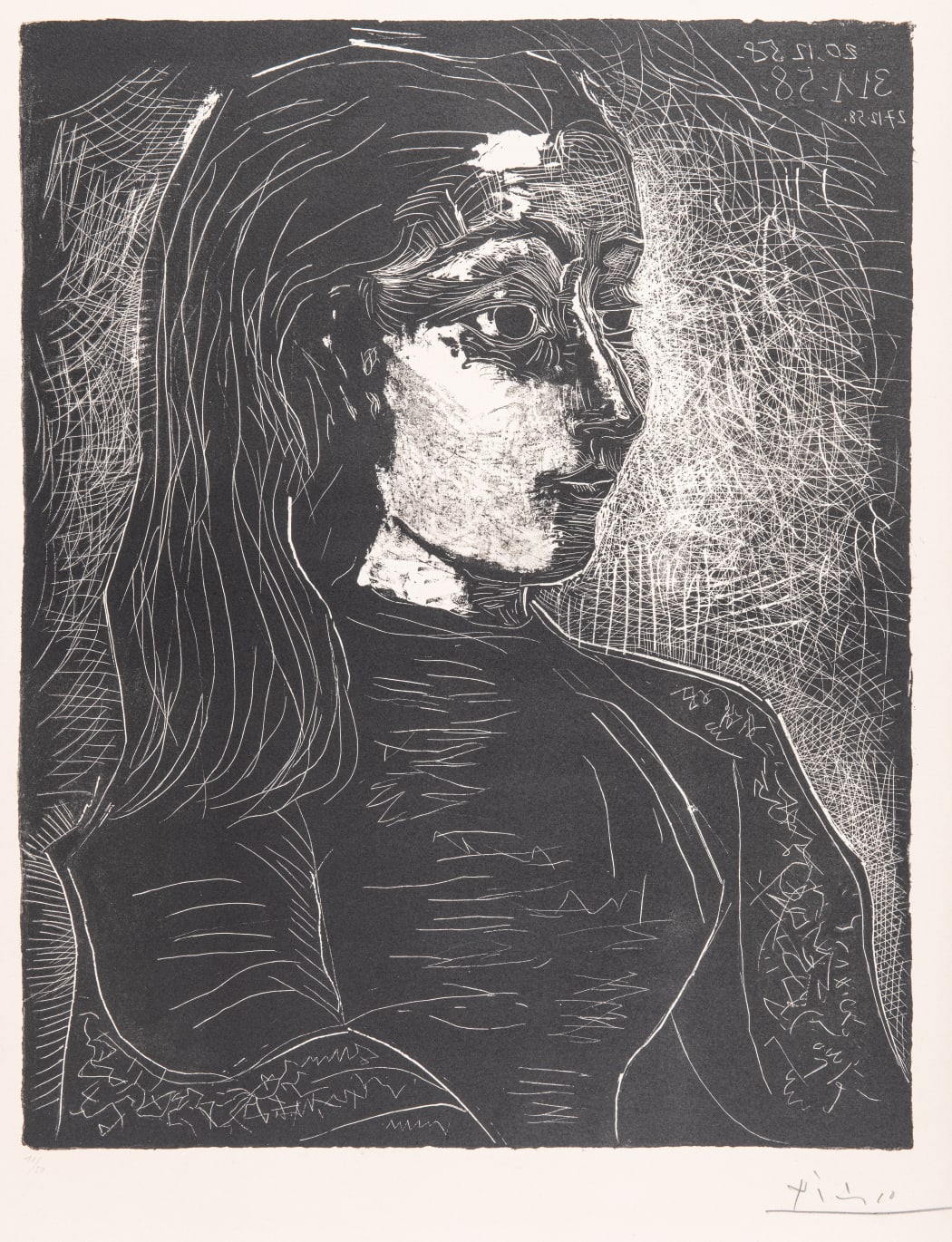

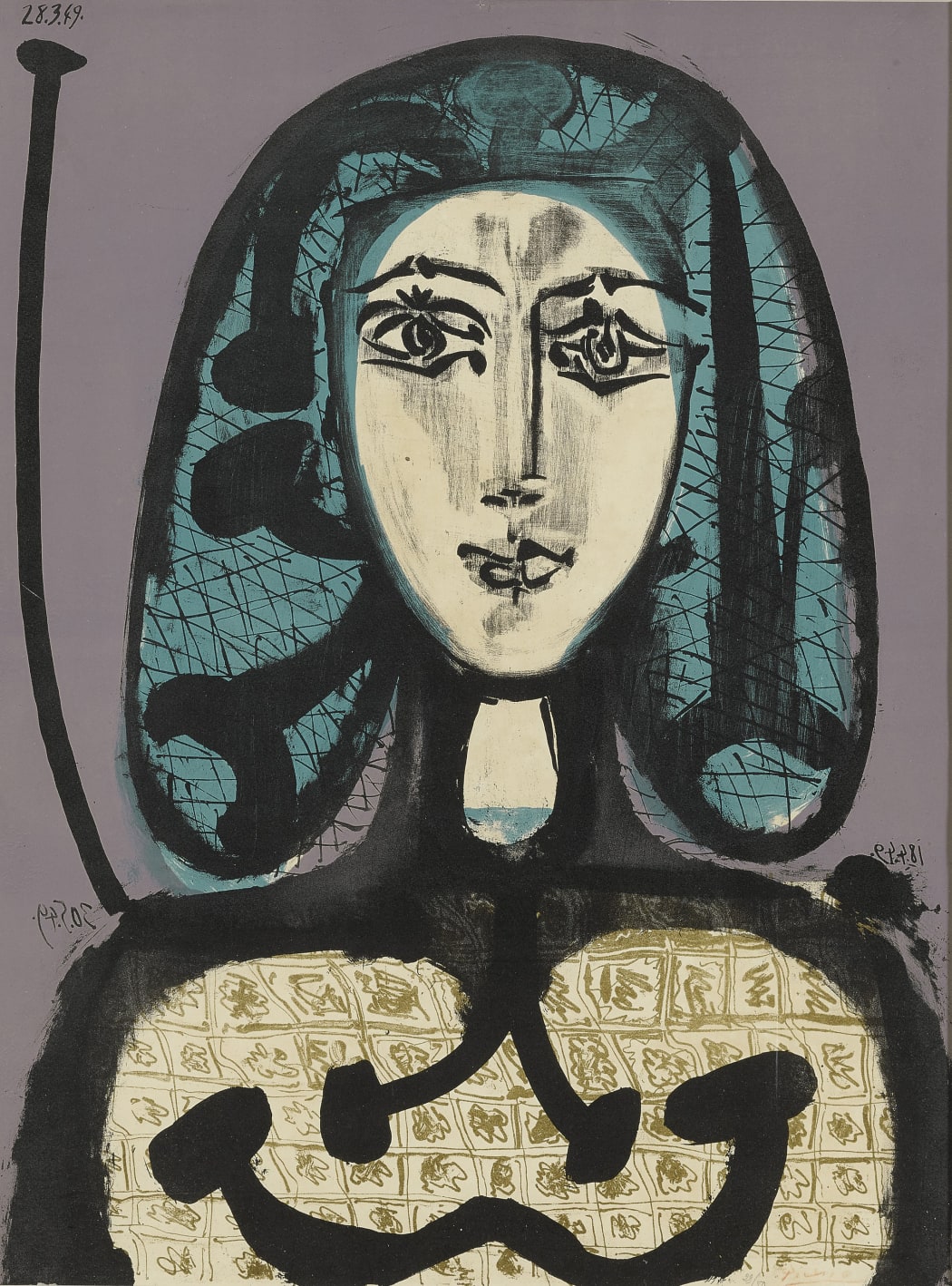

Portrait de Jacqueline (Ba1245), 1963, linocut, 29 3/4 x 24 3/8 inches

Portrait de Jacqueline (Ba1245), 1963, linocut, 29 3/4 x 24 3/8 inches -

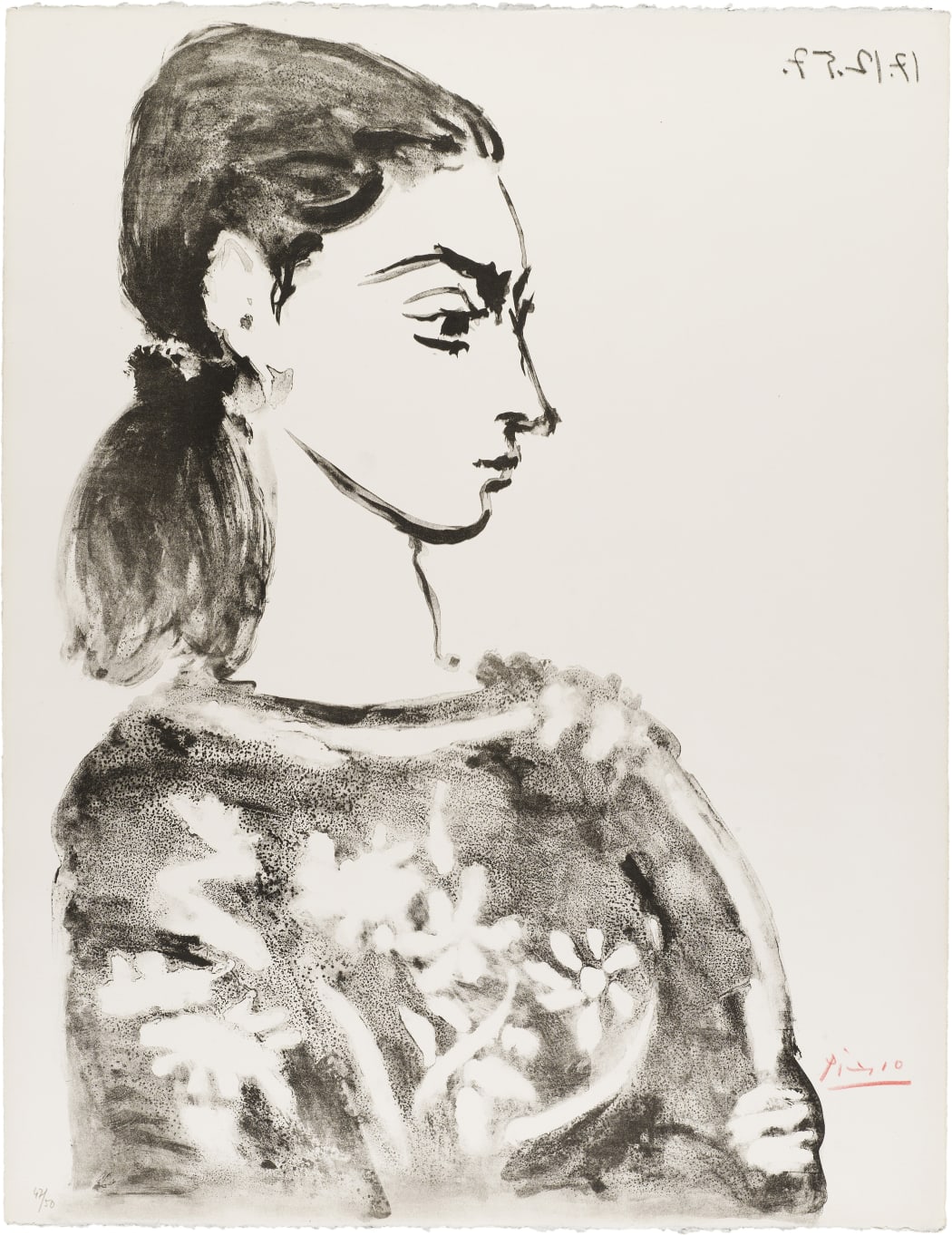

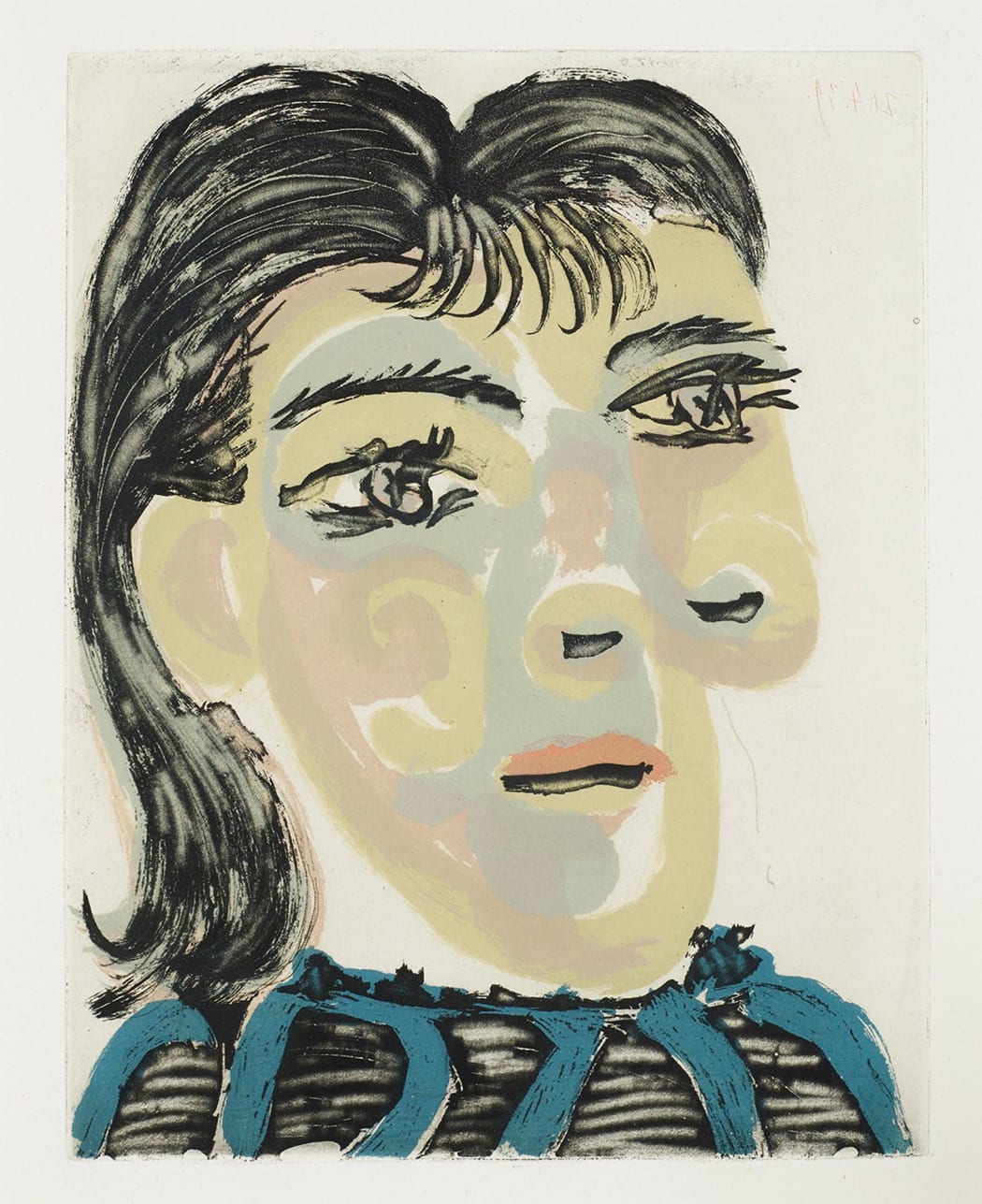

Portrait de Jacqueline aux cheveux lisses (Bloch 1066), 1962, linocut, 29 5/8 x 24 7/16 inches

Portrait de Jacqueline aux cheveux lisses (Bloch 1066), 1962, linocut, 29 5/8 x 24 7/16 inchesLast week Picasso stumbled across Hidalgo Arnéra’s printmaking shop while in Vallauris, working on his pottery craft and enjoying life with Jacqueline, away from Paris. There, he learned about the possibilities of a new technique – one that necessitated much less fuss than lithography and etching, which had required him to courier stones and plates to faraway studios. There is carefree Mediterranean warmth and joyous, playful linework in prints like Portrait de Jacqueline aux cheveux lisses (B1066) – above – and Portrait de femme a la fraise et au chapeau (B1145) – below – showcasing Picasso’s inclination for his new skill, the way it seemed to complement the sunning, behatted visages of his post-Parisian life. Of course, there is also color – color used in a way that Picasso only rarely did before in his prints. The history of Picasso’s colored linocuts is a notch in his master printmaker belt – a canto in the tale of his constant reinvention of printmaking techniques.

The story begins with Picasso’s first published linocut, B859, created in 1958. The image is a modernization of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s famous painting, “Portrait of a Woman” (1564). Picasso stayed quite true to the original — he retained the shadow behind the subject, the corner of curtained backdrop — but took his own liberties with color and shape. Some people say that, in true form, he replaced Cranach’s subject’s face with the unmistakable features of Jacqueline — a believable fiction, if it is one. Though it was a vibrant and widely successful use of a new palette, and is today a print admired, in Picasso’s mind the print’s value was in its challenges.

And the primary challenge he’d faced was in the registration of color. Through all the states he created of B859, he’d had difficulty with it; each color used in the print corresponded to a different sheet of linoleum, which meant that he needed to cut several sheets with the reverse of pieces of the overall image. It was a time-consuming process, tedious. And it would produce a color registration that was less than clean-cut, at that. To reduce the time needed to lay the color, and to enhance the cleanness of the registration, Picasso thought of a shortcut. the “reduction” technique – one credited to his invention and that was cultivated with the support of his printer, Arnéra.

In simplest terms, he found a way to use only one sheet of linoleum on which he could lay down color sequentially, starting first with the largest area and ending with the smallest area. Throughout the process, the surface of the linoleum would be cut down, so that at the end just a very small bit of material would remain – the last color printed. Because the cut-away parts get discarded, there is no way to correct mistakes; the printmaker has one shot. Perhaps it was the thrill of this task, the masterful facility it required, that incited Picasso’s early 1960s spree of colored linocuts.

In any case, the happy result are images like B1066, in which primary color bubbles up like bloom in Jacqueline’s cheeks, like the sun glinting off of one side of her face; and B1145, in which color becomes the planes of her face themselves, her face stamped into Picasso’s imagination in light. It is the deceiving simplicity of these images, their ease and iconography, combined with the inventiveness of the artist which has raised them to a status of genius.

But as always, there was more innovation ahead. Next up, he’d find it in the bathtub. More on that next week.

* Lieberman, William S. Picasso Linoleum Cuts: The Mr. and Mrs. Charles Kramer Collection,

(1985) (pp. 11-12)

-

Nature Morte au Verre sous La Lampe (Bloch 1101), 1962, linocut, 24 7/16 x 29 9/16 inches

Nature Morte au Verre sous La Lampe (Bloch 1101), 1962, linocut, 24 7/16 x 29 9/16 inches -

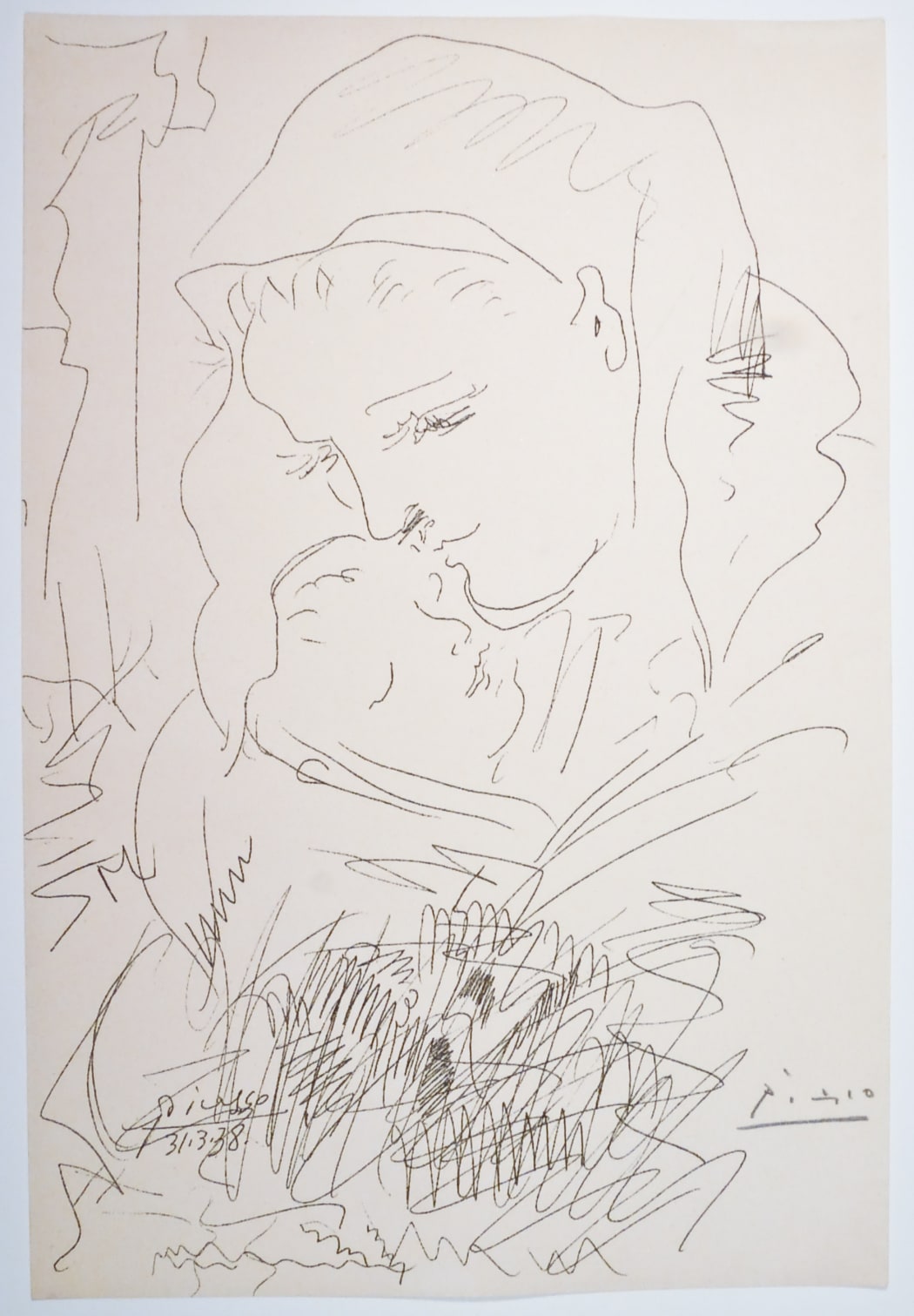

Maternité (Bloch 1829), 1938, Hectograph, 12 3/16 x 8 3/16 inches

Maternité (Bloch 1829), 1938, Hectograph, 12 3/16 x 8 3/16 inches -

Jacqueline de Profil à droite (Bloch 854), 1958, lithograph, 22 x 17 3/8 inches

Jacqueline de Profil à droite (Bloch 854), 1958, lithograph, 22 x 17 3/8 inches -

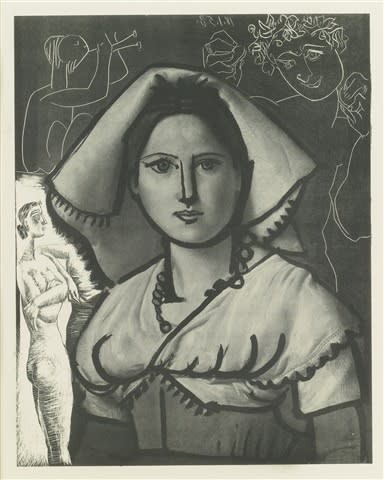

Femme au Corsage à Fleurs (Bloch 846), 1957, lithograph, 25 1/2 x 19 5/8 inches

Femme au Corsage à Fleurs (Bloch 846), 1957, lithograph, 25 1/2 x 19 5/8 inches -

L'Italienne (d'aprés le tableau de Victor Orsel) (Bloch 740.1), 1953, Lithograph and engraving, 17 1/2 x 15 inches

L'Italienne (d'aprés le tableau de Victor Orsel) (Bloch 740.1), 1953, Lithograph and engraving, 17 1/2 x 15 inches -

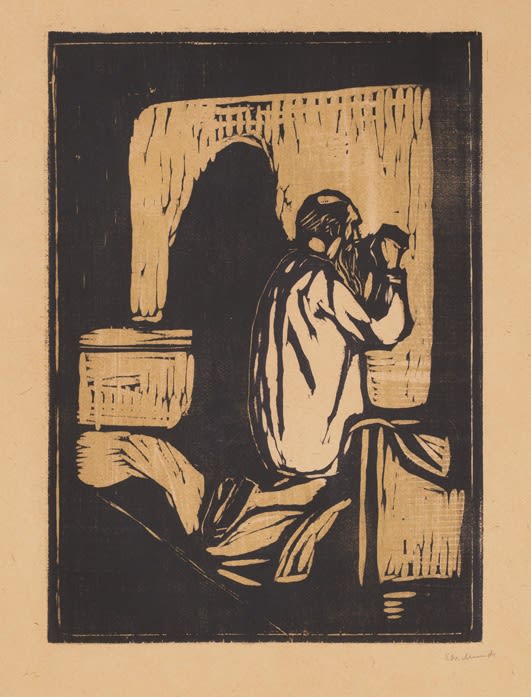

Old Man Praying (Woll 205), 1895, woodcut, 18 3/16 x 13 inches

Old Man Praying (Woll 205), 1895, woodcut, 18 3/16 x 13 inches -

La Femme a la Fenêtre 1949 (Bloch 695), Sugarlift aquatint, 32 5/8 x 18 1/2 inches

La Femme a la Fenêtre 1949 (Bloch 695), Sugarlift aquatint, 32 5/8 x 18 1/2 inches -

Femme Au Fauteuil No 4 (d'aprés le violet) (B588), 1949, lithograph, 27 7/8 x 20 1/2 inches

Femme Au Fauteuil No 4 (d'aprés le violet) (B588), 1949, lithograph, 27 7/8 x 20 1/2 inches -

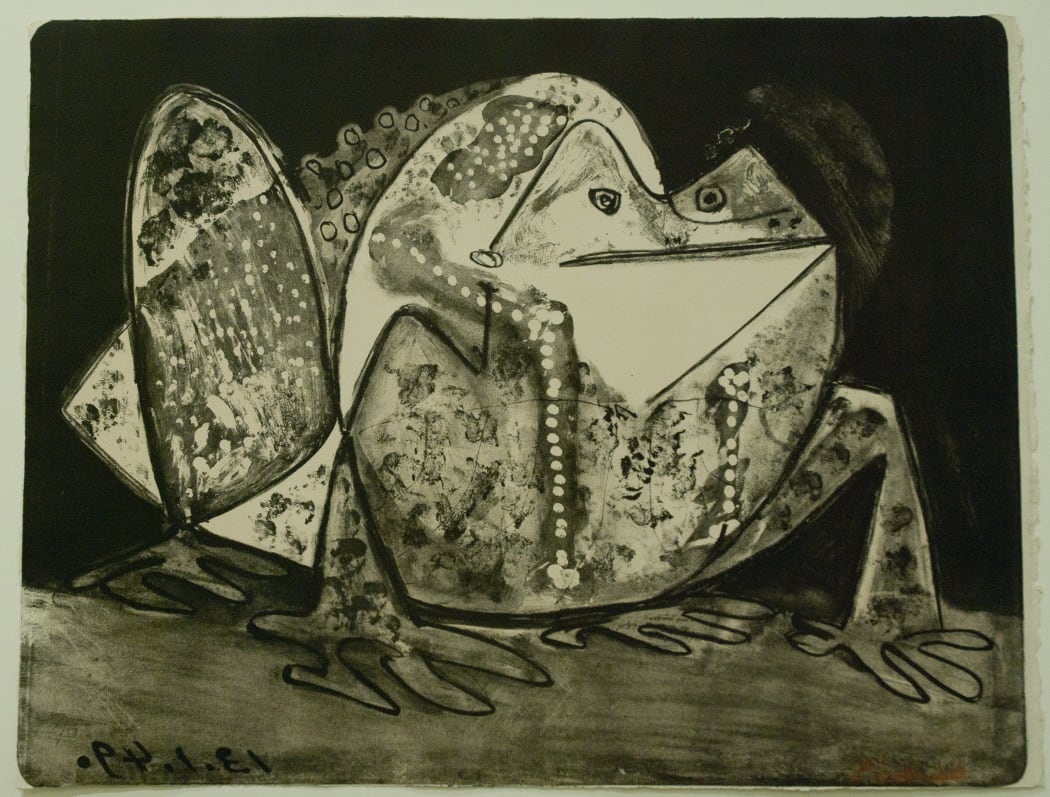

B0585 Le Crapaud, (Bloch 585)), 1949, lithograph, 19 1/2 x 25 1/4 inches

B0585 Le Crapaud, (Bloch 585)), 1949, lithograph, 19 1/2 x 25 1/4 inches -

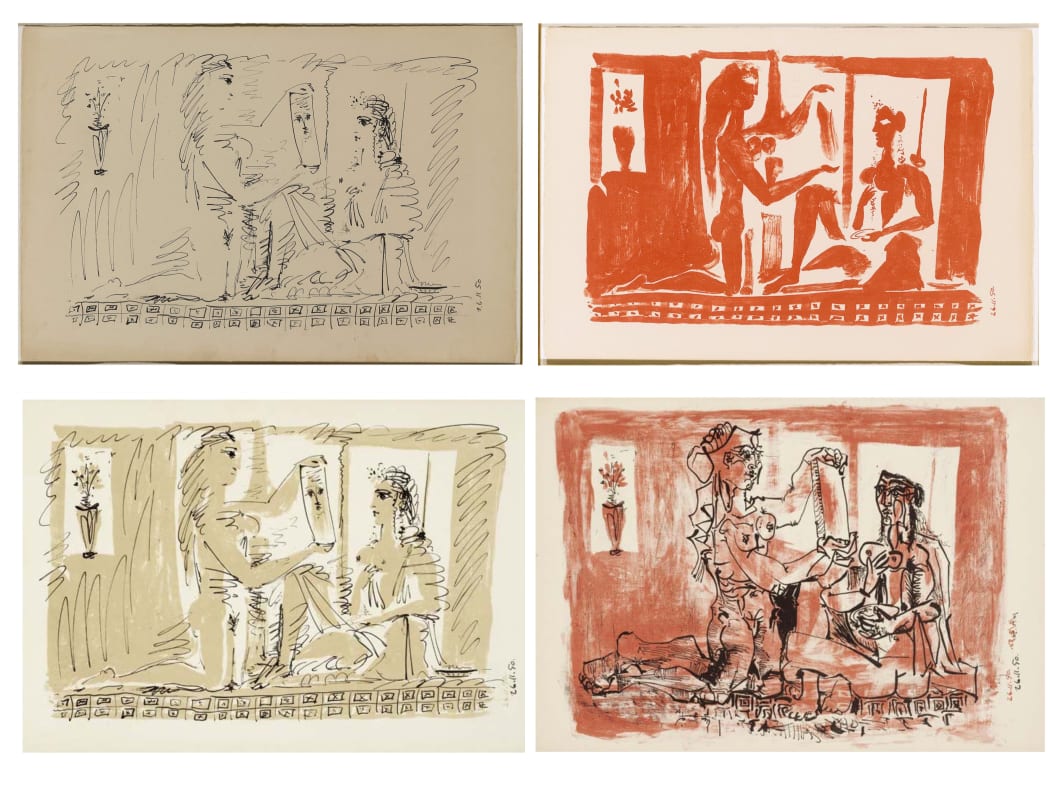

Upper left & right: La Femme au Miroir (Woman at the Mirror) (M197 1st state), 1950, lithograph, 12 3/8 x 19 3/4 inches Lower left & right: La Femme au Miroir (Woman at the Mirror) (M197 each one of five state proofs), 1950, lithograph, 12 1/2 x 18 inches

Upper left & right: La Femme au Miroir (Woman at the Mirror) (M197 1st state), 1950, lithograph, 12 3/8 x 19 3/4 inches Lower left & right: La Femme au Miroir (Woman at the Mirror) (M197 each one of five state proofs), 1950, lithograph, 12 1/2 x 18 inches -

Profil de Femme (Bloch 436), 1947, lithograph, 22 1/8 x 15 inches

Profil de Femme (Bloch 436), 1947, lithograph, 22 1/8 x 15 inches -

La Femme à la Résille (Femme aux Cheveux verts) (Bloch 612), 1949, lithograph, 25 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches

La Femme à la Résille (Femme aux Cheveux verts) (Bloch 612), 1949, lithograph, 25 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches -

Portrait de Dora Maar au Chignon. II (Bloch 292), 1936, drypoint, 20 1/4 x 15 3/4 inches

Portrait de Dora Maar au Chignon. II (Bloch 292), 1936, drypoint, 20 1/4 x 15 3/4 inches

This time last year, Punxsutawney Phil the Groundhog’s shadow was still, as it had been for the prior 133 years, an (albeit minor) national concern – would he see it and condemn us to six more weeks of winter? Or would he be relieved of it, blissfully unaware, and usher in the gleaming promise of an early bloom? And though it turned out to be the latter, we are all acutely aware that the period following Phil’s emergence was quite far from gleaming. As we enter this February, with the significant weight of last year in front of us as much as behind us, it hardly seems worth mentioning that Phil guessed more winter on Tuesday. What is the change of season anyway, if our feelings remain the same? (This sentiment rings more true for us lovers of art than for, say, meteorologists.)

For our long-term readers, looking at the print above may evoke a very Groundhog Day-eque feeling – the Bill Murray kind, not the Phil kind. Haven’t we looked at this print before? Back in December, we introduced to our series a formative figure in Picasso’s life, Dora Maar. At that time, we considered a work from the year they are said to have fallen in love, 1936: Portrait de Dora Maar au chignon (B291). In B291, Dora gazes off the page dreamily, the light catching in her long, feminine eyelashes and appearing to twinkle even on the whiteness of the page. She is idealistic, youthful, ennobled. Part II of that work (B292), pictured above, is a rendering of the very same woman, though crafted with a small difference in characterization. In B292 Dora’s demeanor is changed. She is stonier, dignified. There is a wrinkle to her brow – perhaps it’s consternation (another war was, after all, inching closer and closer to home), or some frustration with her lover, the artist himself. Her round, earnest eyes have turned hard as diamonds: dazzling, intense, a world unto themselves. The shift in the two Doras is as subtle as the change in season – our best clue in the change of days is the sameness of the features; the budding of leaves on boughs days before barren is understandable by the fixedness of the bough. Studying the two prints side-by-side tells us just as much about Dora as about Picasso; they are his diary entries, windows into his world in October of 1936.This story seems somehow continued in Picasso’s 1939 work Femme au fauteuil: Dora Maar (B318). By this time, Dora’s image had become recognizable, the subject of many well-known portraits in print and in paint. As we will discuss further in coming weeks, she was already known as Picasso’s Weeping Woman, so-called for the series of portraits in which her face itself seems disfigured, ripped open by her despair; her emotion is turned inside out. Fittingly, in B318 Dora appears contrary to her depictions a few years before. Whereas before she was spirited, now she is chair-bound, her hair let down from its elegant coif and her dress more matronly than fashionable. One hand is curled around the arm of the chair while the other hangs absently, mirroring the emotion that plays out on her face – one of pointed despair; a sense of absence that feels intentional, performative, as much as it does deeply private. And her eyes – Dora’s most striking, most awe-inspiring feature – are downcast, no longer staring off the page with a rapturous intensity, but further into it. Even the mode of her rendering has changed; Picasso uses aquatint instead of drypoint, in effect reinforcing the much-softened aura of his subject. It is evident that Picasso’s feelings have changed – they’ve deepened, developed; he sees the same features but never the same subject. The seasons change again.

The monotony of the pandemic has made a lot of days feel saturated with sameness. But we look to the diary of Picasso’s art and see that there are differences, small shifts, that can be observable in our day-to-days, too, and we know that they will culminate over time – even (or, especially) when we are looking at the same, beloved features of our lives. We hope that our friends in the American Northeast take a moment to enjoy the snow this week, and we thank our friend Phil for showing up on Tuesday to teach us our yearly lesson, regardless (or, in spite of) the weather.

Take care, and ‘til next week. -

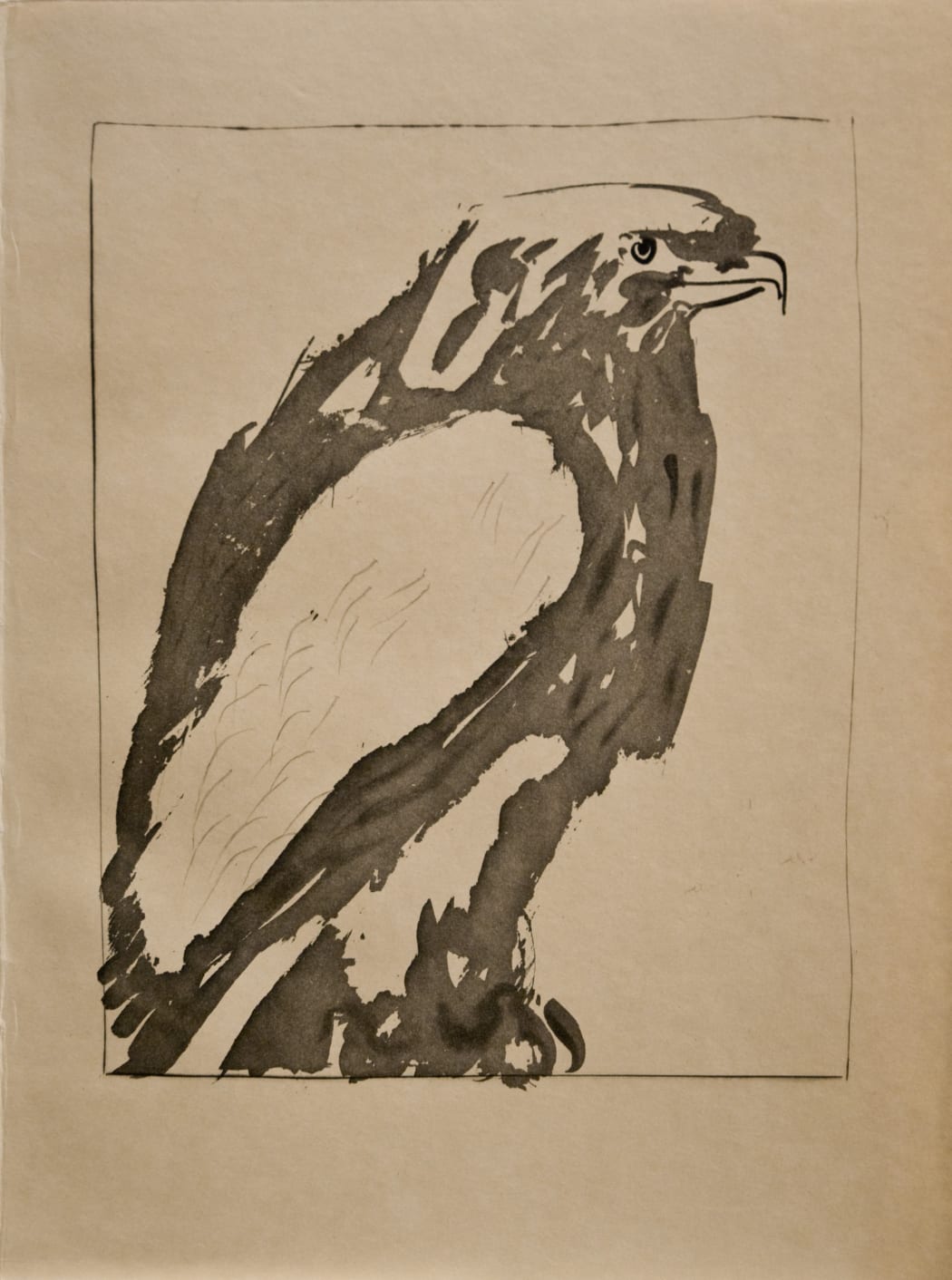

L'Aigle Blanc (The Eagle) (Bloch 340), 1936, sugarlift aquatint, drypoint, and scraper, 14 3/8 x 11 inches

L'Aigle Blanc (The Eagle) (Bloch 340), 1936, sugarlift aquatint, drypoint, and scraper, 14 3/8 x 11 inches -

Tête de Femme de Profil (Bloch 6), 1905, drypoint, 21 5/8 x 15 9/16 inches

Tête de Femme de Profil (Bloch 6), 1905, drypoint, 21 5/8 x 15 9/16 inches -

Salomé (Bloch 14), 1939, aquatint, 17 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches

Salomé (Bloch 14), 1939, aquatint, 17 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches -

Tète de femme No. 7. Portrait de Dora Maar(B1336), 1939, aquatint, 17 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches

Tète de femme No. 7. Portrait de Dora Maar(B1336), 1939, aquatint, 17 1/2 x 13 1/4 inches -

Tête de Femme No. 2. Portrait de Dora Maar (B1340), 1939, aquatint, 17 3/4 x 13 1/4 inches

Tête de Femme No. 2. Portrait de Dora Maar (B1340), 1939, aquatint, 17 3/4 x 13 1/4 inches -

Le Dindon (The Turkey) B346, 1936, Sugarlift aquatint, drypoint, burin and scraper, 14 3/8 x 11 inches

Le Dindon (The Turkey) B346, 1936, Sugarlift aquatint, drypoint, burin and scraper, 14 3/8 x 11 inches -

Femme au Fauteuil songeuse, la Joue sur la Main (S.V. 21) B218, 1934, engraving, 17 5/8 x 13 5/8 inches

Femme au Fauteuil songeuse, la Joue sur la Main (S.V. 21) B218, 1934, engraving, 17 5/8 x 13 5/8 inches -

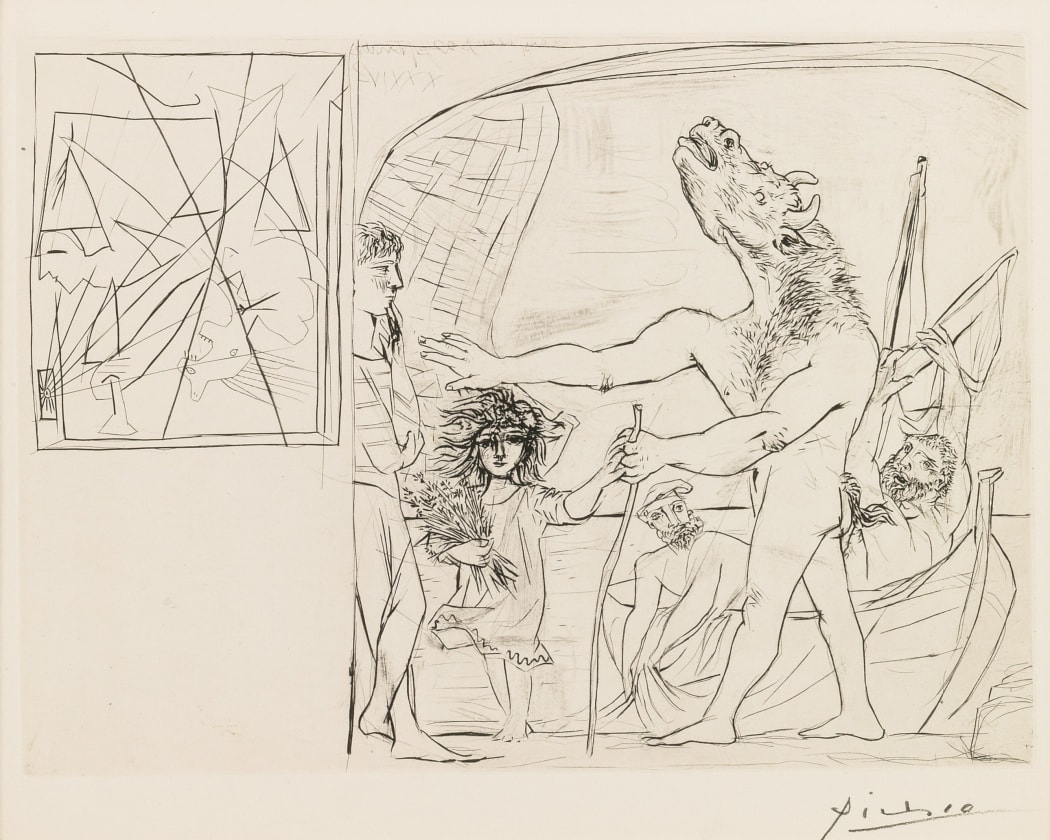

B0223 Minotaure aveugle guidé dans la Nuit par une Petite Fille au Pigeon (S.V. 96)) (B223), 1934, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches

B0223 Minotaure aveugle guidé dans la Nuit par une Petite Fille au Pigeon (S.V. 96)) (B223), 1934, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches -

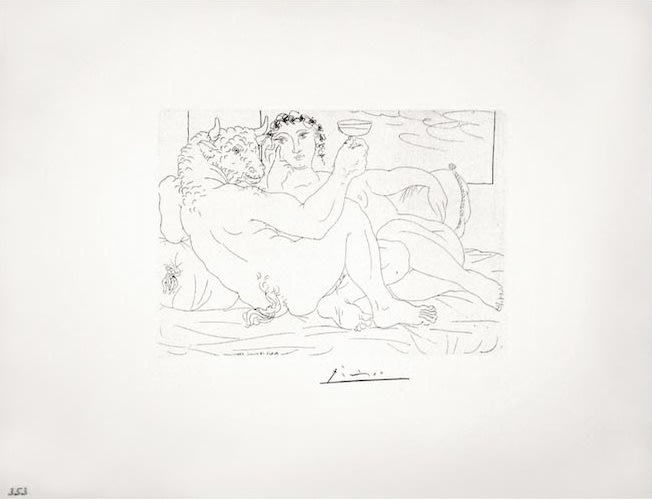

Le Repos du Minotaure : Champagne et Amante (S.V. 83), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches

Le Repos du Minotaure : Champagne et Amante (S.V. 83), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches -

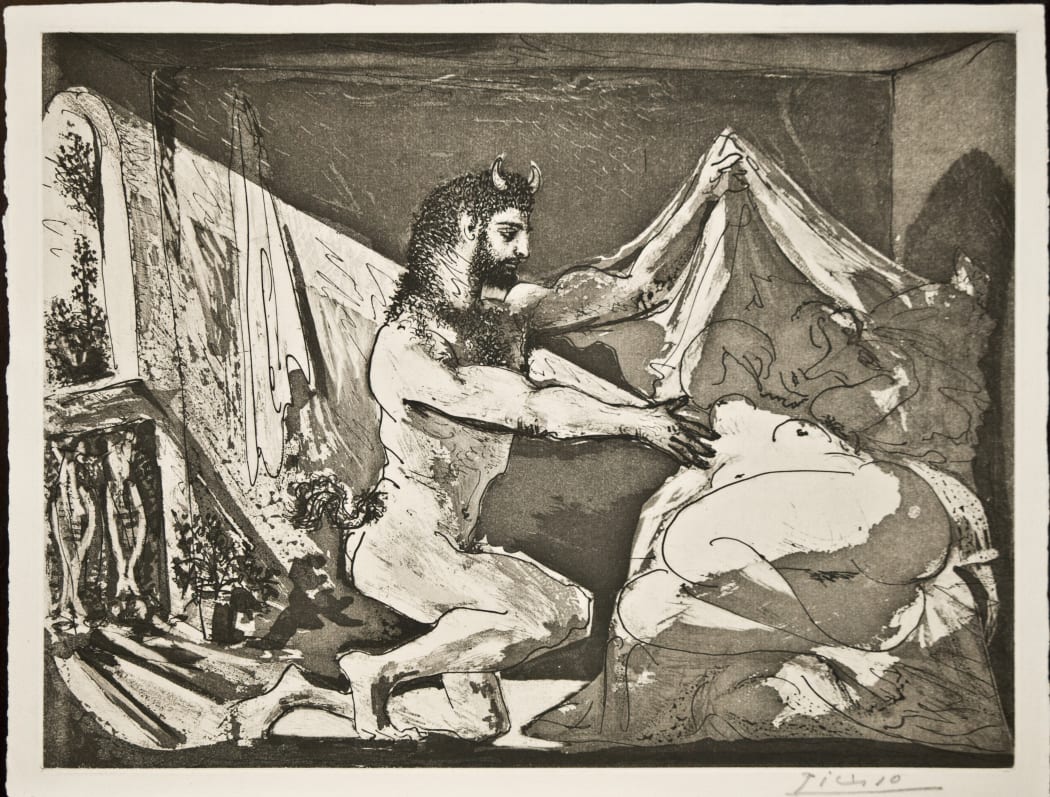

Faune dévoilant une Dormeuse (Jupiter et Antiope, d'après Rembrandt) (S.V. 27) (B230), 1936, Sugarlift aquatint and burin with scraper, 13 1/4 x 17 1/2 inches

Faune dévoilant une Dormeuse (Jupiter et Antiope, d'après Rembrandt) (S.V. 27) (B230), 1936, Sugarlift aquatint and burin with scraper, 13 1/4 x 17 1/2 inches -

Marie-Thérèse en Femme Torero (B220), 1934, etching, 17 5/8 x 13 5/16 inches

Marie-Thérèse en Femme Torero (B220), 1934, etching, 17 5/8 x 13 5/16 inches -

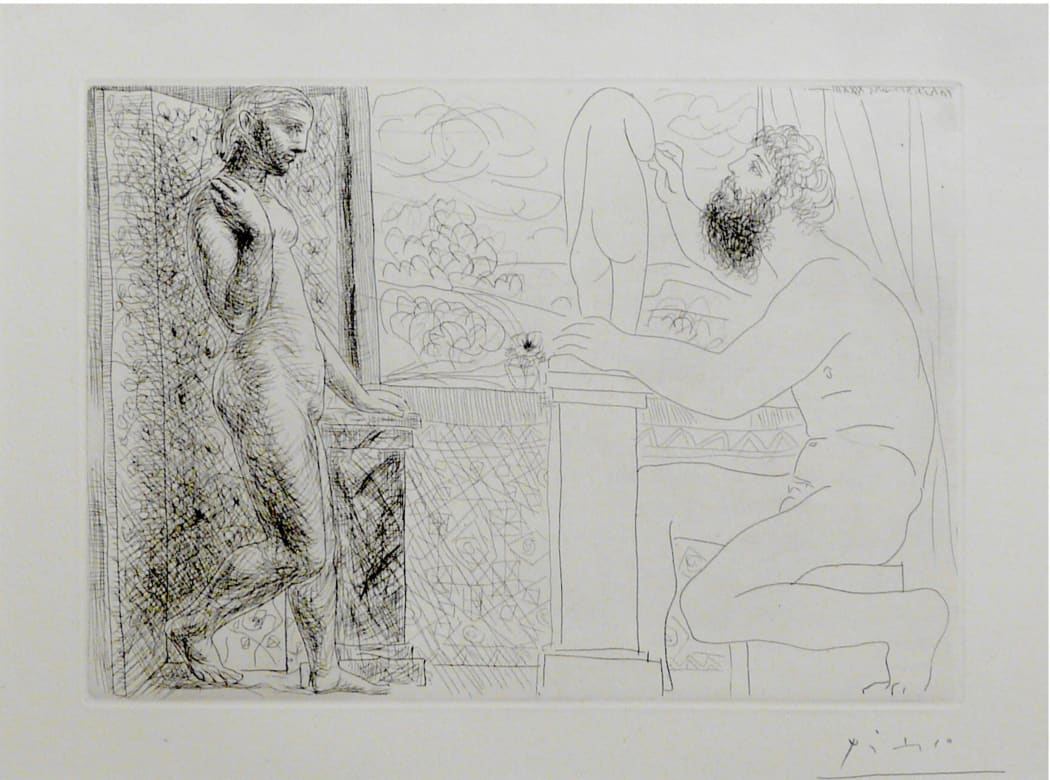

Sculpteur et son modèle devant une fenêtre (B168), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches

Sculpteur et son modèle devant une fenêtre (B168), 1933, etching, 15 1/4 x 19 3/4 inches -

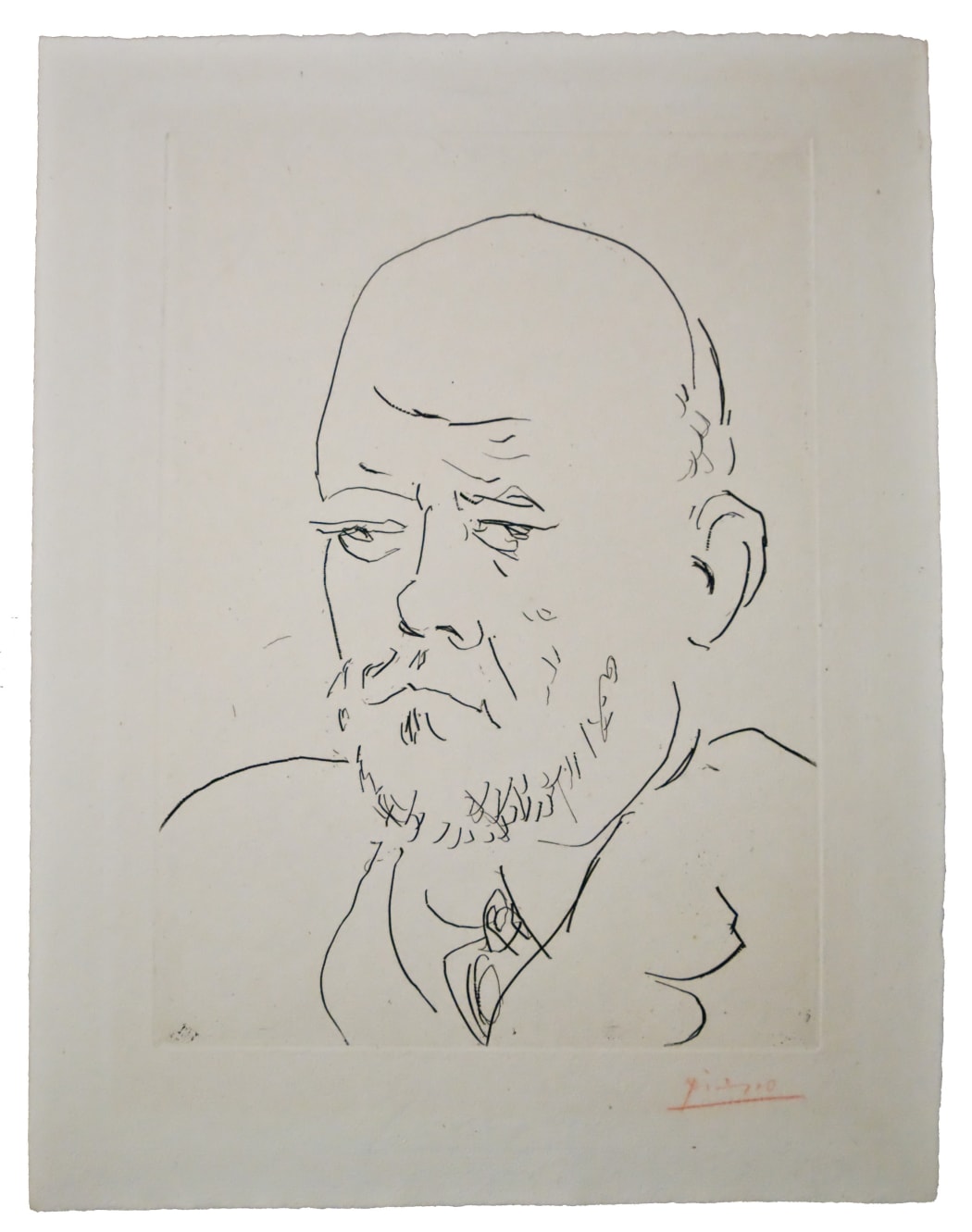

Portrait de Vollard IV (B233), 1933, etching, 17 1/2 x 12 3/8 inches

Portrait de Vollard IV (B233), 1933, etching, 17 1/2 x 12 3/8 inches -

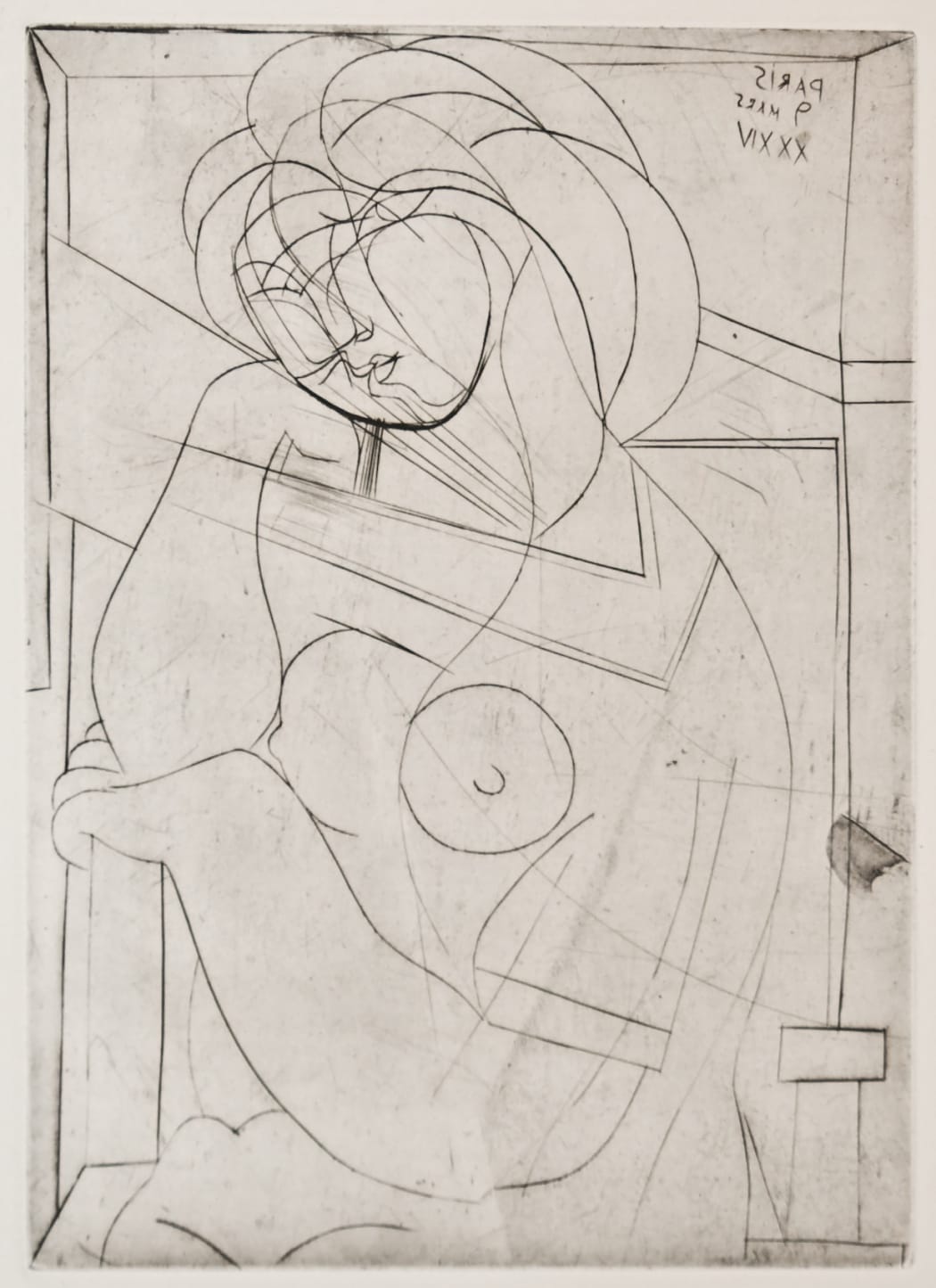

Orphée, ou le poète. II Ba541, 1933 (February 3, Paris), Monotype, 9 7/8 x 6 3/4 inches

Orphée, ou le poète. II Ba541, 1933 (February 3, Paris), Monotype, 9 7/8 x 6 3/4 inches -

Muse montrant à Marie-Thérèse pensive son Portrait sculpté B257, 1933 (March 17.III, Paris), etching, 16 7/8 x 13 1/4 inches

Muse montrant à Marie-Thérèse pensive son Portrait sculpté B257, 1933 (March 17.III, Paris), etching, 16 7/8 x 13 1/4 inches -

Sculpture, Tête de Marie-Thérèse B250, 1933, drypoint, 18 3/8 x 14 1/2 inches

Sculpture, Tête de Marie-Thérèse B250, 1933, drypoint, 18 3/8 x 14 1/2 inches -

Visage de Marie-Thérèse B95, 1928 (Probably October, Paris), lithograph, 20 3/8 x 13 1/8 inches

Visage de Marie-Thérèse B95, 1928 (Probably October, Paris), lithograph, 20 3/8 x 13 1/8 inches -

Portrait d’Olga au Col de Fourrure(Ba109), 1923, drypoint, 30 1/4 x 22 1/8 inches

Portrait d’Olga au Col de Fourrure(Ba109), 1923, drypoint, 30 1/4 x 22 1/8 inches -

La Source / Femme au chien (Z.IV.no.301), 1921, pencil drawing on cream vellum paper, 19 7/16 x 25 1/8 inches

La Source / Femme au chien (Z.IV.no.301), 1921, pencil drawing on cream vellum paper, 19 7/16 x 25 1/8 inches -

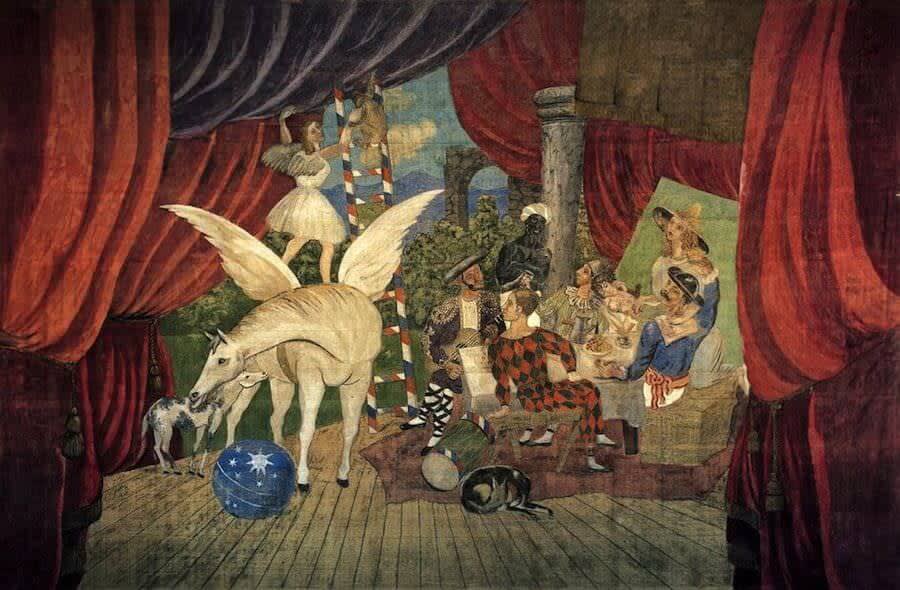

Pablo Picasso: Parade, 1917

Pablo Picasso: Parade, 1917 -

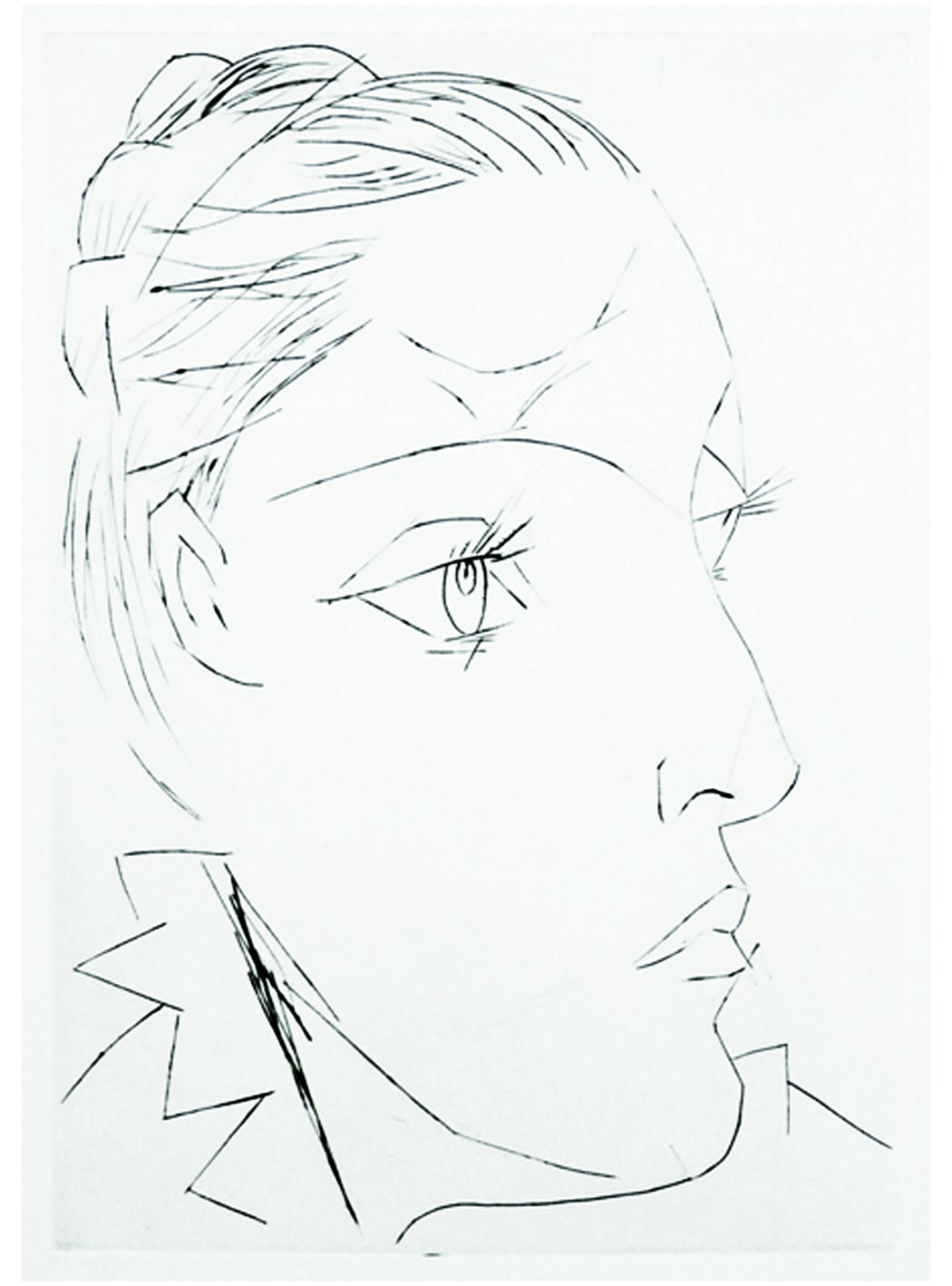

Portrait de la Fille de Charles Morice, 1906, pencil drawing on paper, 26 3/4 x 18 7/8 inches, John Szoke Gallery Collection

Portrait de la Fille de Charles Morice, 1906, pencil drawing on paper, 26 3/4 x 18 7/8 inches, John Szoke Gallery Collection -

Apollinaire blessé, 1916, graphite pencil and conté crayon on paper, 31.3 x 23.1 cm

Apollinaire blessé, 1916, graphite pencil and conté crayon on paper, 31.3 x 23.1 cm -

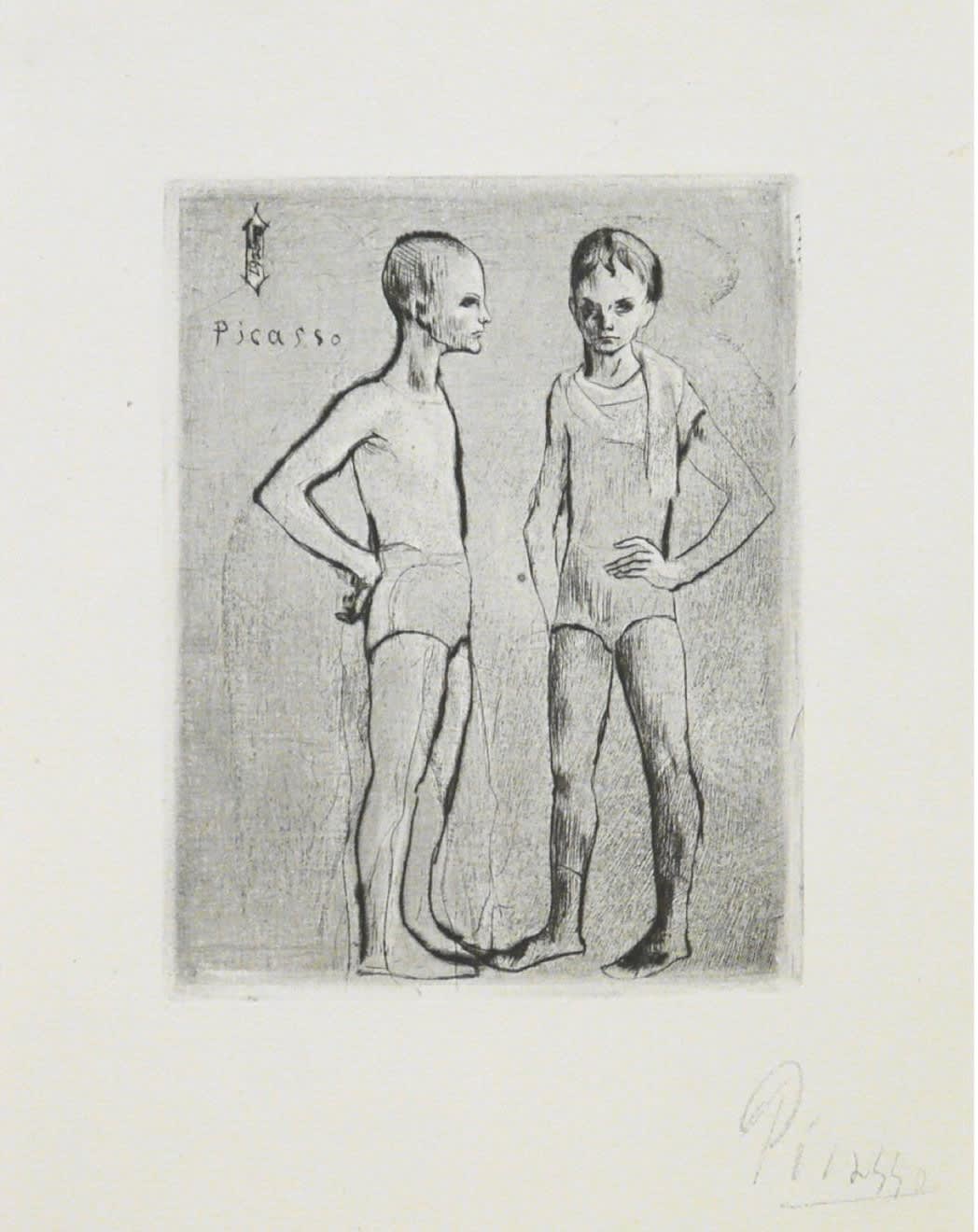

Pablo Picasso: Les Deux Saltimbanques (Bloch 5), 1905, drypoint, 8 3/8 x 5 1/2 inches

Pablo Picasso: Les Deux Saltimbanques (Bloch 5), 1905, drypoint, 8 3/8 x 5 1/2 inches -

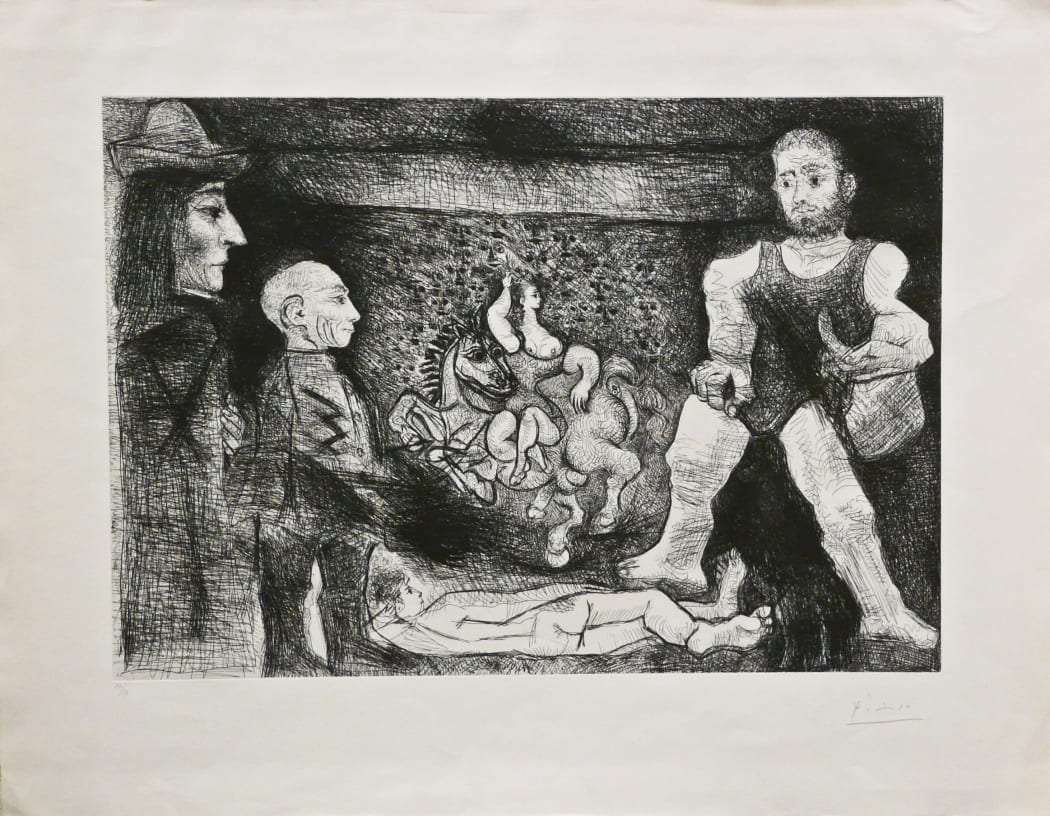

Pablo Picasso: Picasso, son oeuvre, et son Public B1481, 1968, etching, 22 1/2 x 28 inches

Pablo Picasso: Picasso, son oeuvre, et son Public B1481, 1968, etching, 22 1/2 x 28 inches -

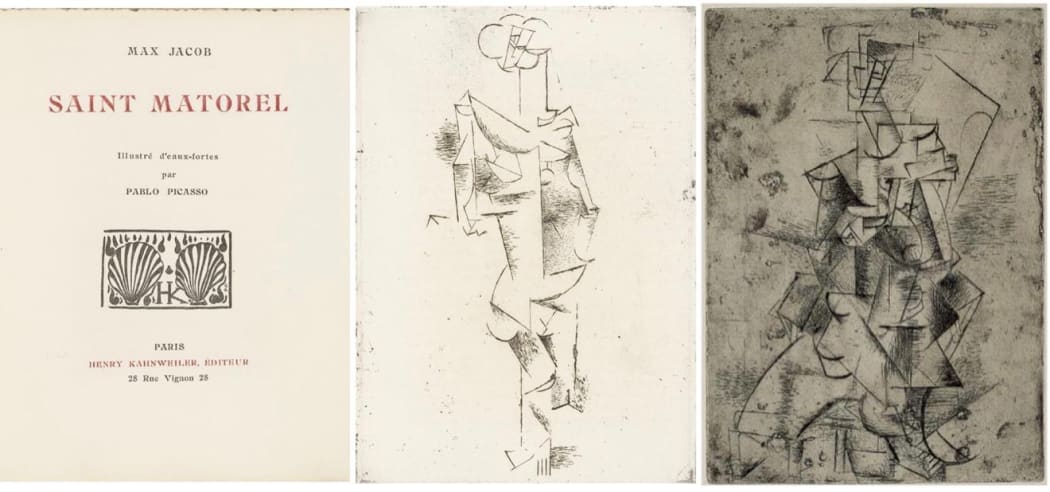

Left: Max Jacob: Saint Matorel illustrated with etchings by Picasso, 1910, published 1911; Middle: Pablo Picasso: Mademoiselle Léonie, 1910, etching, 7 15/16 x 5 9/16 inches; Right: Pablo Picasso: Mademoiselle Léonie Sur Une Chaise Longue, 1910-1911, etching and drypoint, 7 13/16 x 5 9/16 inches ©MoMA

Left: Max Jacob: Saint Matorel illustrated with etchings by Picasso, 1910, published 1911; Middle: Pablo Picasso: Mademoiselle Léonie, 1910, etching, 7 15/16 x 5 9/16 inches; Right: Pablo Picasso: Mademoiselle Léonie Sur Une Chaise Longue, 1910-1911, etching and drypoint, 7 13/16 x 5 9/16 inches ©MoMA -

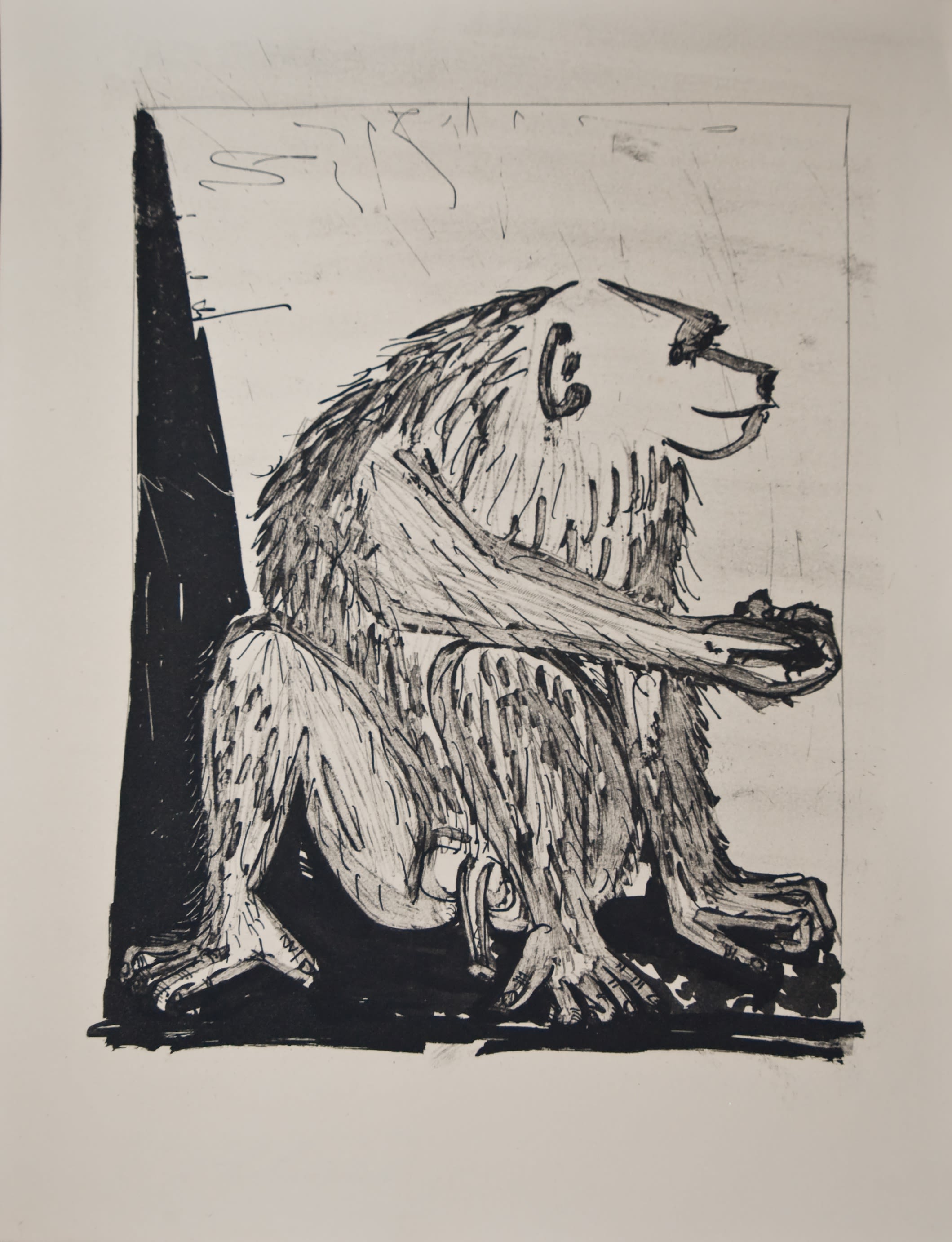

Pablo Picasso: Le Singe (The Monkey), 1936, Sugarlift aquatint, drypoint, and scraper, 14 3/8 x 11 inches

When Picasso relocated from the Montmartre-based Bateau Lavoir (shared with Max Jacob, among many other bohemians and artists), he upgraded to the kind of city-center flat affordable to an artist with new money, playing domestic with his then-girlfriend Fernande Olivier. Despite Fernande’s supposedly reigning status in the household, there was only one lady allowed free roam of Picasso’s in-home studio: Monina, his pet monkey.

One can imagine a melancholy Fernande, relatively neglected during this highly productive time in Picasso’s art-making, sighing over her journal as she wrote about Monina, who, “used to eat all her meals with Picasso and pester him incessantly,” though, she admits, “he bore with this and even enjoyed it. He would let her take his cigarette or the fruit he was eating. She would nestle up to his chest, where she felt quite at home.”*

An unexpectedly sweet image: work-absorbed Picasso, punctuating his self-consuming picture-making for a snuggle with his trickster pet monkey. Unlike his other love affairs, Monina is not a major subject of Picasso’s work. Her closest appearance is in Le Singe, a sugarlift aquatint print of a monkey Picasso created later in his career. That monkey is not Monina, but there is a gentle familiarity in its rendering that may speak to an image of her in the artist’s mind – an impression of her, resting against his heart.It leads me to wonder: what kind of person might be uncovered if we read between the lines of Picasso’s visual diaries? We think we know this artist so well, with his anarchic, larger-than-life persona – but who might we discover if we take a step back from these big narratives, and consider the underdogs of his pictures?

Over the next couple of weeks, we seek to find out.

*Olivier, Fernande. Loving Picasso. Harry N. Abrams, 2001. -

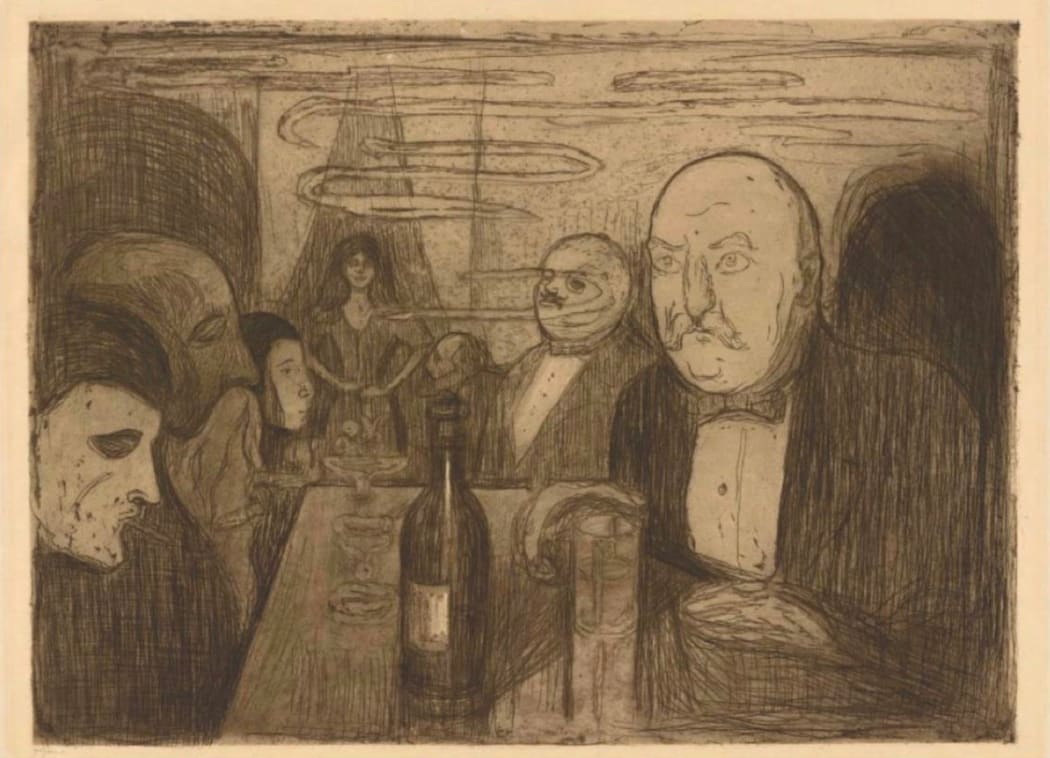

Edvard Munch: Kristiania Bohème II W16, 1895, drypoint, 29.7 x 39.5 cm ©Munchmuseet

Edvard Munch: Kristiania Bohème II W16, 1895, drypoint, 29.7 x 39.5 cm ©Munchmuseet -

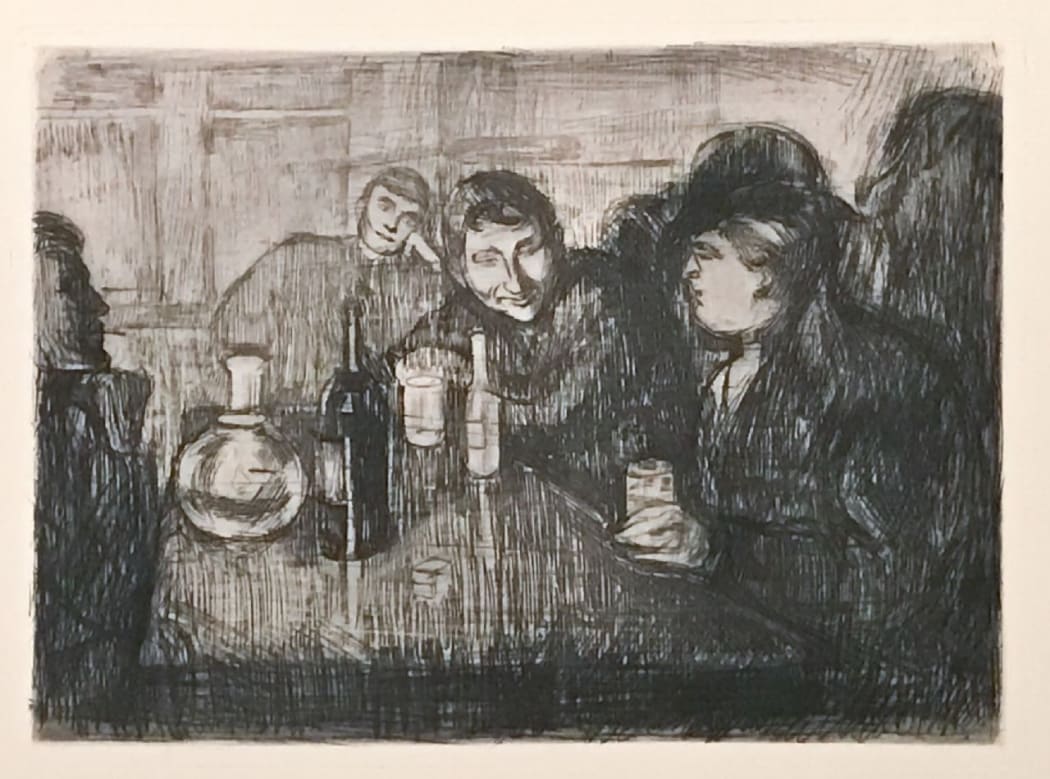

Edvard Munch: Kristiania Bohème I W015, 1895, etching, 13 1/2 x 18 7/8 inches.

Edvard Munch: Kristiania Bohème I W015, 1895, etching, 13 1/2 x 18 7/8 inches. -

Løsrivelse II / Separation II W078, 1896, lithograph, 21 x 30 9/16 inches

Løsrivelse II / Separation II W078, 1896, lithograph, 21 x 30 9/16 inches -

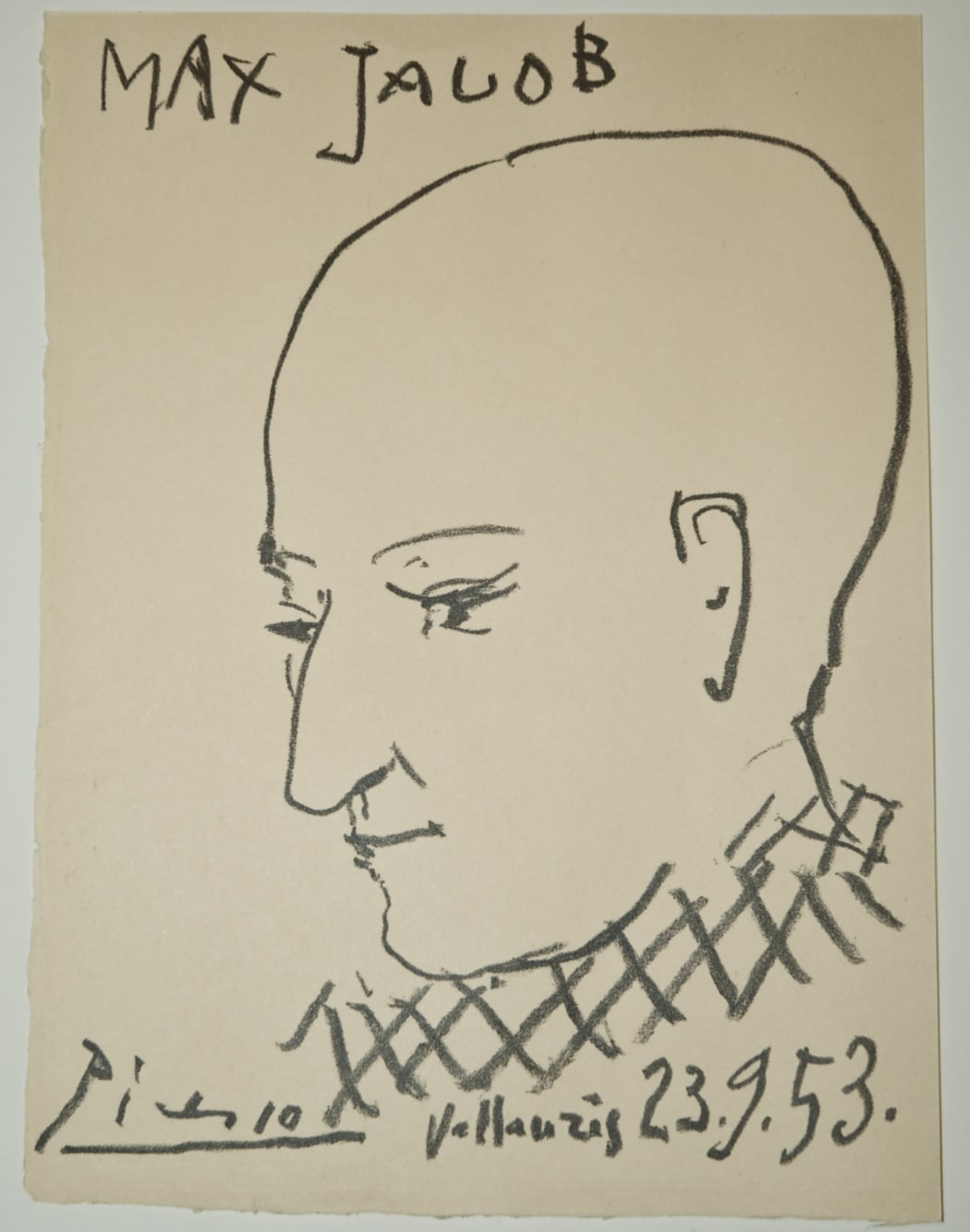

Portrait de Max Jacob, 1953, transfer lithograph, 9 1/2 x 7 1/8 inches

Portrait de Max Jacob, 1953, transfer lithograph, 9 1/2 x 7 1/8 inches -

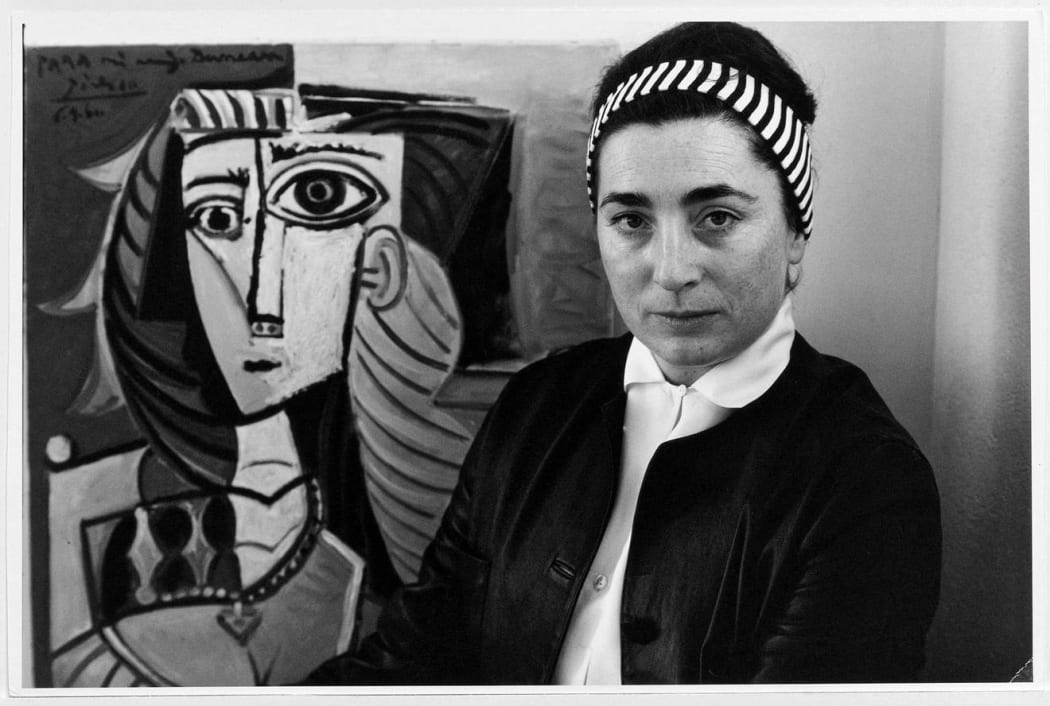

© David Douglas Duncan

© David Douglas Duncan -

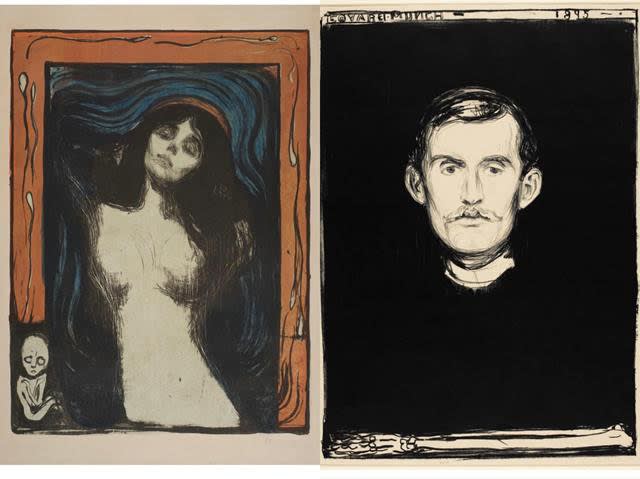

Left: Edvard Munch: Madonna, 1895-1902, lithograph, 23 5/8 x 17 3/8 inches Right: Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm, 1895, lithograph, 22 15/16 x 16 15/16 inches

Left: Edvard Munch: Madonna, 1895-1902, lithograph, 23 5/8 x 17 3/8 inches Right: Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm, 1895, lithograph, 22 15/16 x 16 15/16 inches