An integral part of Picasso’s life as a small child in Malaga, the corrida is one of his oldest themes: as an eleven-year old he sketched at the bullring; at the age of twelve he did a series of studies of bulls; at thirteen he drew caricatures of picadors and matadors. During a visit to Madrid when he was sixteen, he sent his father a detailed portrait copied from a nineteenth century print of the famous torero Pepe Illo; two years later when he created his first etching in 1899, it was the representation of a picador, El Zurdo. These works were the prelude to countless drawings, prints and paintings made throughout Picasso’s long life in which he explored every aspect of the bull, the bullfighter and the bullring.

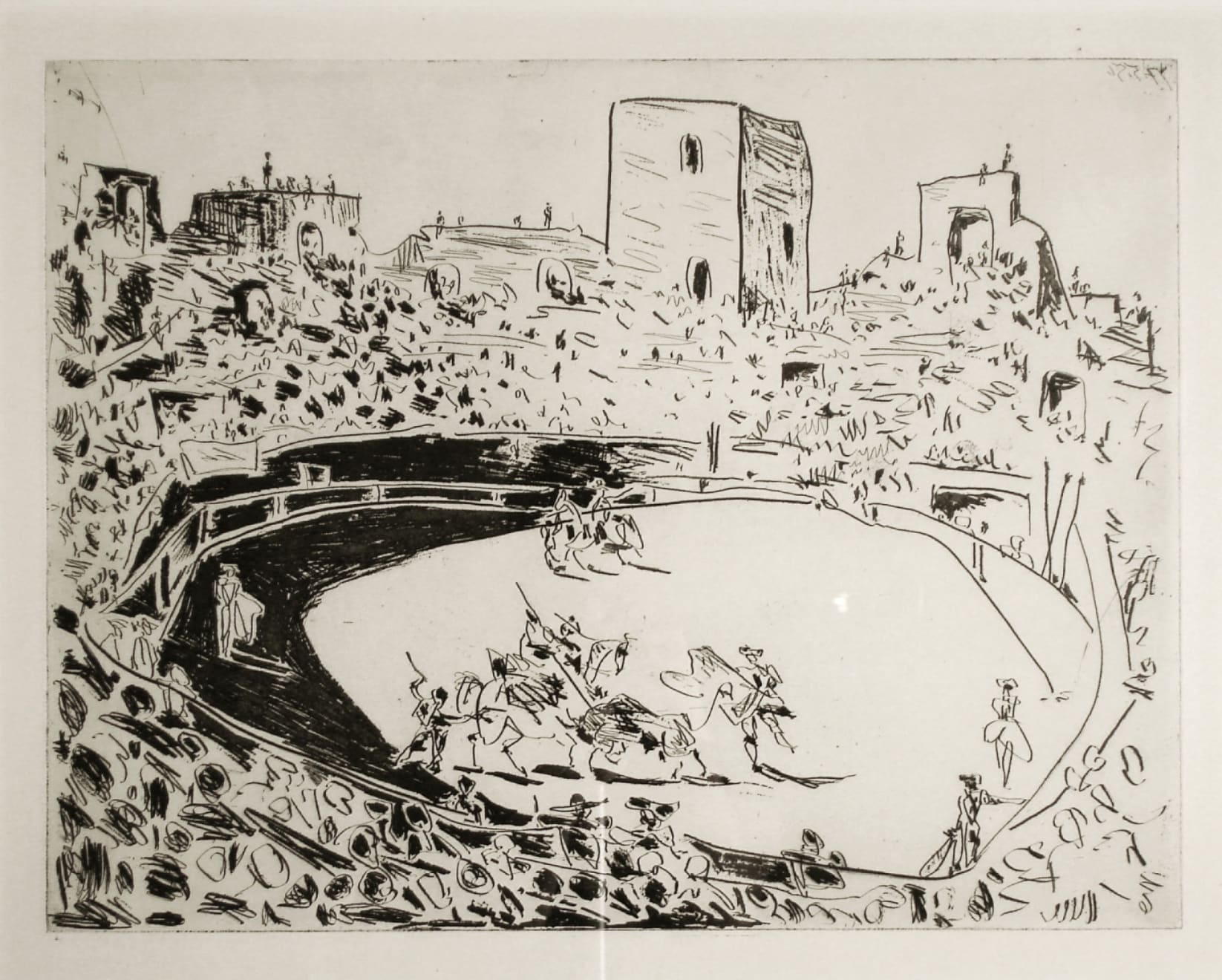

In the years following the Second World War, when the war-time restrictions of movement were lifted and he was able to return to the sunny Mediterranean he loved so much, these themes became particularly significant in his work. After his permanent relocation from Paris to the Côte d’Azur in 1948, Picasso attended bullfights regularly, most frequently at his favorite venues in the Roman arenas of Nîmes and Arles. Corrida en Arles shows one such Sunday event: the circular enclosure in which the ritualized spectacle takes place, surrounded by the crowds of spectators below the ancient monuments of the city—a square tower and a series of ruined arches at the back of the arena. The drama of the spectacle is magnificently illuminated by the sun; visible only by its effects in the first two states, it appears as a large brilliant orb in the third state onwards, its powerful rays extending far across the sky. The many states that Picasso took this print through indicate the importance that its subject had for him; introducing color from the third state, he emphasized the vivid excitement of the event. In the first two states, even before the sun is introduced, a heightened sense of atmosphere is created by the black shadow that falls across the left side of the image, darkening the heads of the audience and a semi-circular area around the edge of the arena, and casting shadows below the central protagonists. The figures of the matadors, picadors, horses and the bull are indicated with lines that the artist scraped into the waxy layer on the copperplate using a penknife, before acid was applied. The energy of these rapidly-drawn lines conveys a strong sense of movement—in particular the diagonal downwards thrust of the picador’s lance into the bull’s shoulder, arresting the momentum of his charge towards the man on his horse. At the bull’s rear, a matador brandishes his cloak, its elegant swirls an essential part of the corrida’s ritualized dance.

Coinciding with the end of the war, Picasso began a new relationship with the beautiful young artist, Françoise Gilot. They met in 1943 and she moved into his Paris home at rue des Grands Augustins in April 1946, bearing him two children, Claude and Paloma in 1947 and 1949 respectively. At the same time, Picasso began an intense engagement with the medium of lithography, as a result of meeting the master lithographer Fernand Mourlot in 1945. Alongside portraits of Françoise—whose flowing locks transform her face into a beaming sun— images of bulls and the corrida constitute Picasso’s main subjects in his return to the lithographic medium in 1945. Possibly influenced by the schematic representations of animals painted by early Europeans on the walls of the caves at Lascaux in southwestern France, discovered in 1940 and opened to the public in 1948, many of Picasso’s prints showing corrida scenes, like Corrida in Arles, have a stylized and abbreviated quality that the artist employed to convey the drama of the spectacle rather than the detail of any individual protagonist.

All the different states of Corrida en Arles were printed by Jacques Frélaut in the Paris workshop of Roger Lacourière in 1951. This impression was printed on Montval laid paper with a Montval watermark. It is one of twelve impressions of the first state in which only black ink was used. Subsequent states involved the addition of first yellow, then red. In 1952 and 1955 further proofs were pulled with the addition of small amounts of blue and green.