PABLO PICASSO

Etching printed on Montval laid paper with Vollard watermark

From the Suite Vollard (S.V. 81), edition of 260

Henri M. Petiet embossing stamp, lower right

Inscribed “3b6/R17” in pencil, lower left margin

Printed by Lacourière, 1939

Published by Vollard, 1939

Image: 8 3/4 x 12 3/8 inches

Sheet: 13 3/8 x 17 1/2 inches

Framed: 20 7/16 x 23 1/16 inches

(Bloch 217) (Baer 421.B.d)

Literature

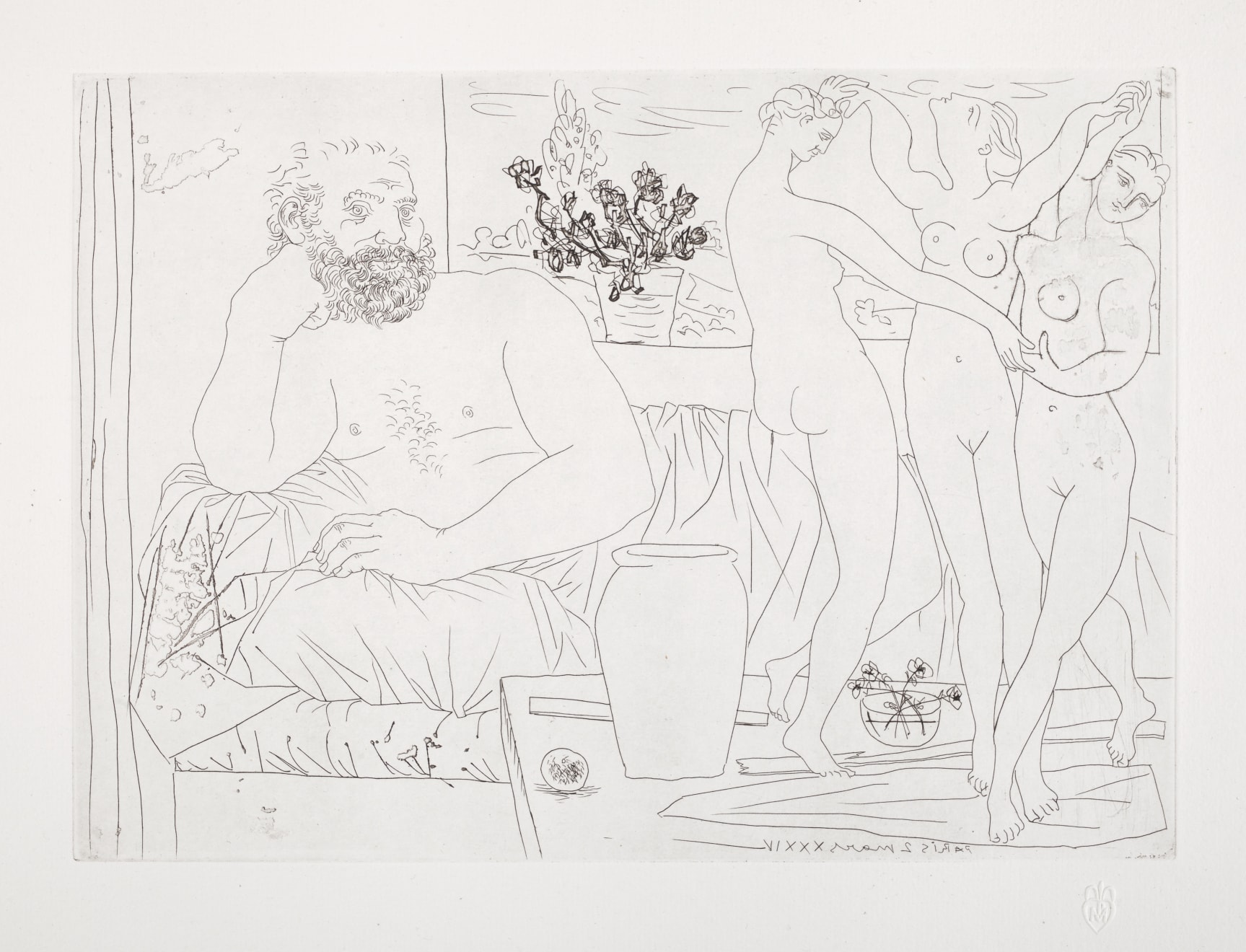

The forty-six etchings of the “Sculptor’s Studio” series have long been understood as a meditation on the nature of art: its creation, its players, and its appreciation. While a majority of the prints show a generalized studio scene, a few are more specific homages to great artists who preceded Picasso. Though the sculptor here could easily be mistaken for the more generalized, almost stereotypically handsome artist who appears in a majority of the images, on second look this man’s hooked nose, balding head, wiry eyebrows, and fleshy cheeks indicate a portrait of an individual, specifically Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1873), a nineteenth-century sculptor who was revered in his time and is still highly regarded in France. His signature style was influential in shaping French identity and visual culture during the Second Napoleonic Empire. His work was collected by royalty and he was commissioned to create a number of highly publicized sculptures for public buildings during Haussmann’s renovation of Paris.

The sculpture at the right is the key to correctly identifying Carpeaux—a variation on his sculpture La Danse, 1865-69, commissioned for the Paris Opera. Parisian society was initially shocked when Carpeaux unveiled the work, which depicts a free-flowing group of nymphs that surround a male figure embodying the spirit of the dance. The naturalism of the cavorting nudes and their proximity to the male at center was thought to be overly suggestive. (Following the general pattern of public art in Paris, it eventually became an icon of the city and is now a source of public pride.) Picasso’s homage to the artist indicates his admiration for the sense of movement Carpeaux was able to covey in La Danse, a quality he has emulated here in his own interpretation of the circle of nudes at right.

Beyond the reference to Carpeaux, it is impossible to ignore the fact that the three dancing women also closely resemble Henri Matisse’s famous paintings and murals on the same theme, particularly in the distortion of the arms and bodies of the three women. The friendly rivalry between Matisse and Picasso is well documented and the elder artist’s influence on Picasso is apparent in several prints of this period. Picasso often visited Matisse’s studio and incorporated the innovations he found there into his own work—which certainly seems to be the case here. Their competitive friendship and mutual regard was explored in depth in the 2002 exhibition Matisse/Picasso at the Museum of Modern Art.

The sculptural group in this image is also reminiscent of Picasso’s earlier etchings on the theme of The Three Graces, which he visited in a handful of prints during the early 1920s. Here, all three women in the sculpture can be clearly identified as Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s mistress. The vase of flowers that sits below the sculptural group enhances the exuberant and sensual nature of the scene.