This is one of the most important etchings in the Suite Vollard as a whole, and the most complex image amongst the forty-six plates of the “Sculptor’s Studio” theme. The series has long been understood as a meditation on the nature of art: its creation, its players, and its appreciation. While a majority of the prints show a generalized studio scene, a few are more specific homages to great artists who preceded Picasso. Scholar Brigitte Baer has effectively argued that Picasso’s inspiration for this image was likely the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), particularly Le Bain Turc (The Turkish Bath), 1862, which depicts a harem of nude women bathing.i Though this controversial painting was in private hands for a number of decades, it entered the collection of the Louvre in 1911, and Picasso was certainly familiar with it. Ingres was among the pantheon of artists Picasso considered to be the major figures in the history of art and he likely studied his work in great detail.

Ingres had a deep appreciation for the sensual pleasures of the feminine body, and his Le Bain Turc has sometimes been dismissed as a hedonistic indulgence in the flesh with little else to recommend it. While Picasso unquestionably shared the elder painter’s fascination with women, his harem is decidedly different in tone. Rather than showing a sea of young, voluptuous nudes, Picasso depicted his women as individuals, using a different style of representation for each of them to convey a variety of personalities. In contrast to the physical abandon of Ingres’ bath scene, Picasso’s image is decidedly more cerebral and symbolic in nature, and shows women in a complex light.

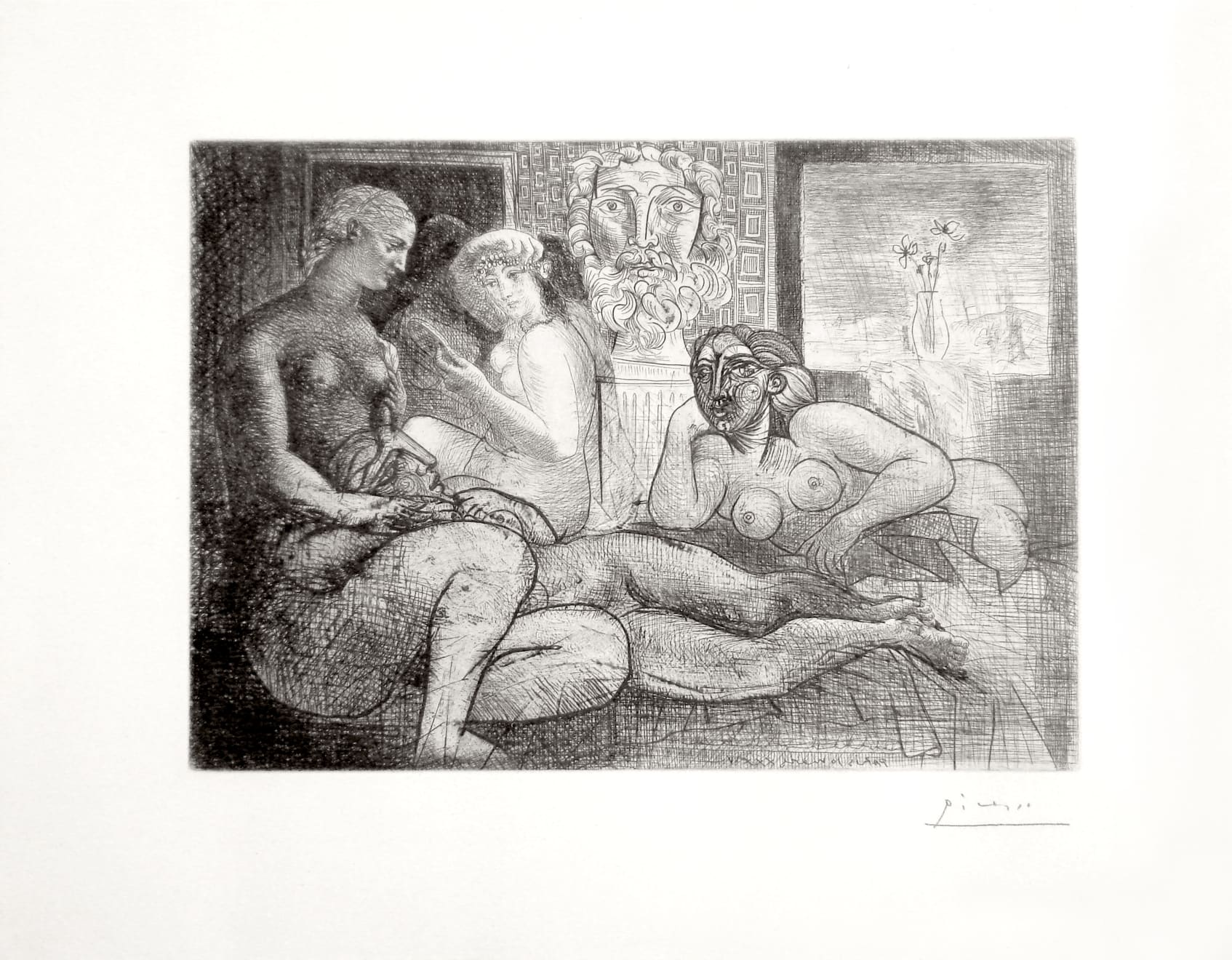

The four women depicted are relaxing in a domestic interior, apparently engaged in conversation. Our eye is immediately drawn to the woman at right, who leans over the bed in a suggestive pose. Her intense, mask-like features, combined with her gaze toward the viewer, command attention. She seems to be listening to the woman whose head rests in the lap of the seated woman at left, both of whom resemble Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s mistress at the time. The woman fixing her dark curly hair at left center is not immediately recognizable, though she appears in a number of other plates of the Suite Vollard, often serving as a counterpoint to Marie-Thérèse. At upper center, a large male portrait head, whose curly locks and luxurious beard recall the Roman portraiture tradition, looms over the women. This head appears in a number of other plates of the Suite Vollard and seems to stand in for the artist when he is not present.

Stylistically, it is interesting to note that the two images of Marie-Thérèse at left represent the evolution of Picasso’s art during their love affair. His earliest portraits of Marie-Thérèse are sweet and naturalistic, in the style of the woman at left, while his later images of her feature a distinctive profile with a prominent fused nose and forehead, which can be seen on the reclining woman. The mask-like face on the woman at right is an example of Picasso’s interest in the art of Africa and Oceania—he is known to have owned an extensive collection of masks that he displayed both in his studio and at home. They served as inspiration throughout his career, taking center stage in his so-called “primitivist” period from 1907-1910, exemplified by his famous 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Selected masks in Picasso’s collection may have also influenced the development of the phallic nose Picasso used to depict Walter, seen here in the reclining figure.ii

Picasso went to great pains to perfect his vision for this plate, taking it through five states, each of which substantially altered the overall impact of the print. In the earliest states, the recumbent figure that stretches across the lower center of the canvas was a more traditional odalisque with her head on a pillow, and the seated woman at left was situated behind her. He then dramatically altered the position of these two women, adding legs to the seated woman and placing the reclined nude’s head in her lap. The preening woman and the sculpted male head at center, as well as the general environs and composition remain similar throughout, but he slowly builds up the shadowing around them, eventually achieving a Rembrandt-like chiaroscuro effect. Picasso deeply admired the Dutch artist, whose position as the undisputed master of etching motivated the Spaniard to equal this achievement, a goal he achieved during this time period, as seen in this plate and several others of the Suite Vollard. However, the most significant and interesting change in the plate is the face of the woman at right, which alters dramatically in the final state to what we see now. In the first four versions of the plate, she is a pretty, voluptuous blond with a sweet expression that is almost cartoon-like. Had Picasso not made this change, it would have been a much less memorable image overall and would likely not hold its current place among his most important prints.

The current impression is from the edition of 260 printed on Montval laid paper watermarked “Vollard” and “Picasso”. (There was also an edition of fifty with wide margins and a separate watermark, and a small edition of three.) It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard estate.

i Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, 79.

ii Deborah Wye, A Picasso Portfolio: Prints from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010, 37.