PABLO PICASSO

Literature

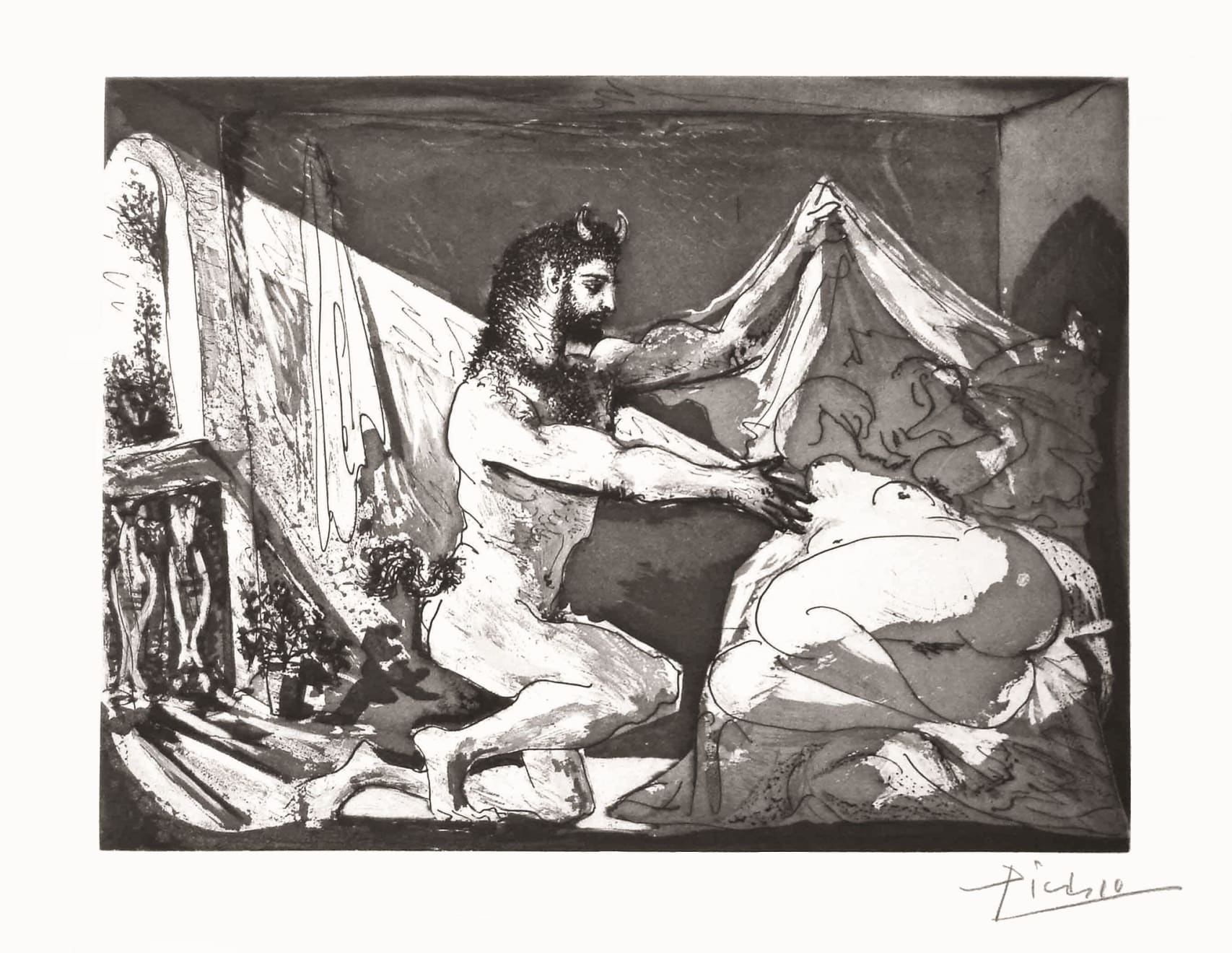

In this image—one of Picasso’s most celebrated prints—a playful satyr lifts the sheets to peek at a sleeping beauty bathed in moonlight. At left is a balustrade that opens to a beautiful summer night. Near it stands a pot of basil. According to medieval Italian folklore, the herb’s heavenly fragrance had the power to transform an animal to a prince under the light of the full moon, and many young maidens placed it by their windows hoping for the arrival of their true love.

Picasso created Faune dévoilant une Dormeuse in June of 1936 after a hiatus of over a year from working on the Suite Vollard. This gap in his work was due to the intense turmoil of 1935, in which his marriage dissolved and his mistress became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter. Yet the pause seems to have served him well. Picasso’s skill as a printmaker grew by leaps and bounds in the mid-1930s and his mastery is evident in the sensitive handling of light and detail in this compelling and, now famous, image. Noted Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer describes it thus: “the more one studies it…the more mysterious and lyrical it becomes, claiming clear title to the label of ‘masterpiece.’”i

Early scholars such as Bolliger describe this print at face value (a faun unveiling a sleeping woman), but scholars have recently shown that it is likely Picasso’s rendition of the Greek myth of Jupiter (Zeus) and Antiope, in which the god disguises himself as a satyr and takes the beautiful nymph as she sleeps (she later bears twins). This story had been painted or etched by a number of important artists throughout history, including Annibale Carracci, Correggio, Rembrandt, Goltzius, Watteau, and Ingres. Amongst these, Rembrandt was a particularly important figure for Picasso—the greatest amongst the greats. As has been demonstrated by scholar Janie Cohn, this etching can be seen as Picasso’s unique interpretation of the Dutch artist’s prints on the same subject, one from 1631 and another from 1659. Picasso’s Antiope is in a similar position to the one used in the old master’s later print, but she is shown from a different angle. In Rembrandt’s earlier etching, the satyr is in the midst of climbing through the window and in the later print he is about to take the young maid. Picasso’s satyr is somewhere between the two points of action, almost filling in the gap. As Cohen notes, “in this case [Picasso’s] imagination was stimulated by the elements of time and movement suggested by [Rembrandt’s] two prints”.ii

Baer agrees with Cohen and goes a step further to discuss the subject of this print in terms of Picasso’s inner world at the time. It is among his last images of Marie-Thérèse Walter, who had been his mistress since 1927. When Picasso etched Faune dévoilant une Dormeuse, he had recently met the Surrealist photographer Dora Maar, who would become his next lover. In this context, Baer sees this etching as a farewell to his relationship with Walter. Like Jupiter (the mythological figure depicted), Picasso was overcome by desire for a beautiful young woman and altered himself in order to have her. Like the myth of Jupiter and Antiope, their liaison resulted in pregnancy. However, as Baer notes, the roguish Jupiter/satyr figure is a considerably more likable beast than the intimidating Minotaur alter-ego of Picasso’s earlier prints. This satyr seems to be relatively tame, indulging in a forbidden pleasure. This change in imagery corresponds to Picasso’s own desire toward his lover, which had become likewise more manageable and subdued and would soon be extinguished altogether.

In terms of technical achievement, this etching is among the most outstanding examples of sugar-lift aquatint. Though extremely challenging, mastery of sugar-lift allows great fluidity of expression, similar to brush and ink. To create a sugar-lift, the artist paints on the copper plate with sugar syrup, which is allowed to dry. The plate is then coated with varnish or hard-ground and placed in a water bath. The sugar solution underneath dissolves, leaving the painted areas exposed. The plate is then put through the process of aquatint: it is dusted with rosin particles that are baked to the surface, and then etched according to the desires of the artist; a full range of tones is possible. The process is quite delicate and easily thwarted at any stage. Picasso had honed his skill in sugar-lift in the previous two years under the tutelage of master printer Roger Lacourière, who was known for his advanced knowledge of the subject. Lacourière’s father had been a renowned practitioner in the technique (some have attributed invention of the method to the elder Lacourière, but this is not the case) and passed his skill to his son. Baer has identified a 1934 etching titled Femme nue assise et trois têtes barbues (Bloch 216) as Picasso’s first use of sugar-lift. He then perfected his technique in early 1936 (just prior to etching the present plate) in a whimsical suite of thirty-one animal images titled Eaux-fortes originals pour les texts de Buffon.

In Faune dévoilant une Dormeuse, Picasso used sugar-lift aquatint to create the subtle areas of shadow that surround the figures and set the nocturnal mood. As discussed by Baer, the plate went through six states in order to achieve the various shades of gray seen here—the artist was not satisfied until he had captured the distinctive light that is cast by a full moon, an astounding achievement that is quite difficult to obtain in the medium of printmaking.iii She notes that he was likely motivated by the example of Rembrandt’s legendary blacks, which he famously envied. It is also likely that Picasso had Goya’s Los Caprichos suite of 1799 in mind as he strove to obtain this elusive effect. Los Caprichos established Goya as a master of sugar-lift aquatint and his skill had not been matched since. Picasso was a highly competitive artist—not only with his contemporaries but also his predecessors—and such art-historical challenges often fueled his work.

The current impression is one of fifty deluxe impressions of the sixth (final) state with large margins printed on Montval laid paper watermarked “Papeterie Montgolfier à Montval,” outside of the edition of 260 (there was also a small edition of three). It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard estate.

i Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, 98).

ii “Picasso’s Dialogue with Rembrandt’s Art” in Etched on the Memory: The Presence of Rembrandt in the Prints of Goya and Picasso. V+K Pub./

Inmerc.: Blaricum, The Netherlands, 2000, 89.

iii Baer, 98.