PABLO PICASSO

From the edition of 50

Printed by Lacourière, 1939

Image: 19 9/16 x 27 7/16 inches

Sheet: 22 3/4 x 30 1/2 inches

(Bloch 1330) (Baer 433.C)

From the edition of 50

Printed by Lacourière, 1939

Image: 19 9/16 x 27 7/16 inches

Sheet: 22 3/4 x 30 1/2 inches

(Bloch 1330) (Baer 433.C)

Literature

In the mid-1930s, Picasso made a handful of etchings that center around the bullfight, depicting a bull, a horse, and a beautiful young female toreador who distinctly resembles his mistress at the time, Marie-Thérèse Walter. The bullfight was a passion of the artist throughout his life and these etchings were not his first foray into the theme—as noted by Museum of Modern Art curator Deborah Wye, a picador was the subject of Picasso’s first print of 1899 and he explored the bullfight throughout his career.[i] The subject of such works range from straightforward gestural expressions of the drama and action of the conflict to highly metaphorical images that explore his private inner life, as in Grande Corrida, avec Femme Torero.

In 1934, Picasso was in his mid-50s and was likely experiencing a sort of mid-life crisis. His relationship with his wife, Olga Khokhlova—a former ballet dancer from Ukraine—was extremely strained and had been so for years. Though a striking beauty in her youth, she was now somewhat ravaged by years of health problems, poor diet, anxiety attacks, and obsessive coffee-drinking. Meanwhile, his long-term liaison with his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, was beginning to disintegrate and she would soon reveal to him that she was pregnant (according to Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer, it was just before Christmas of 1934). Though Picasso biographer John Richardson suggests that Olga may have been aware of the affair as early as 1929 and had come to accept it, the truce was tenuous and Picasso feared that his wife’s wrath could descend at any moment.[ii] In addition to his romantic entanglements, Picasso had been struggling with self-doubt as a result of mixed critical responses to his mid-career retrospectives in Paris and Zurich in 1932.[iii] He was beginning to feel that his life was spinning out of control.

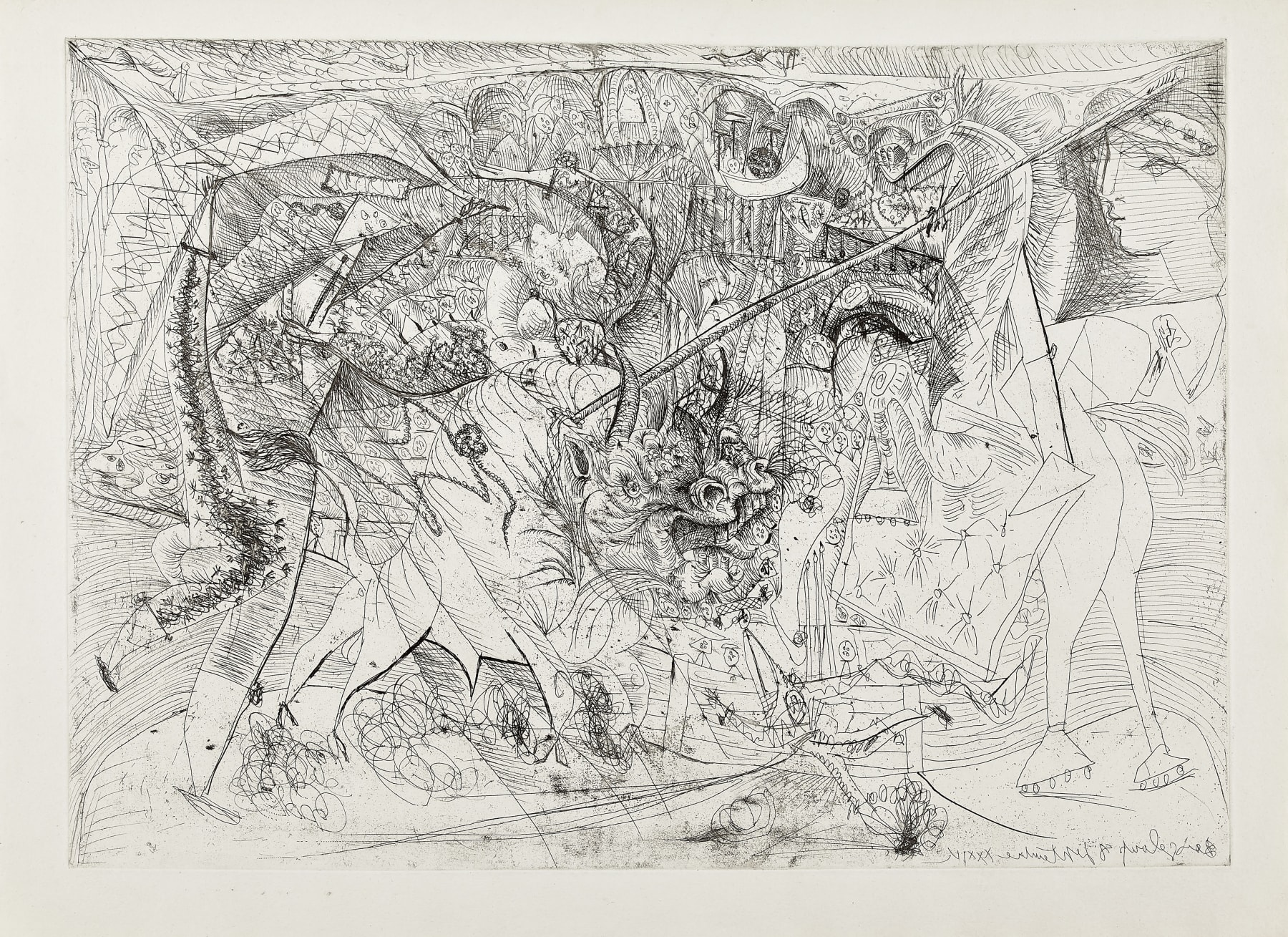

In Grande Corrida, avec Femme Torero and a number of other similar etchings of the period, particularly Femme Torero. Dernier Baiser? (Bloch 1329) and Marie-Thérèse en Femme Torero (Bloch 220), Picasso plays out the terrible pressure he was under in a grand allegory of the bullfight. As interpreted by a number of scholars, Picasso used the figure of the bull to represent himself; while the female toreador, who traditionally rides on horseback, represents his lover Marie-Thérèse. The horse stands for his wife Olga.[iv] Among Picasso’s prints in this vein, each of which are major prints in the history of art, Grande Corrida, avec Femme Torero stands as the most ambitious and intense. Wye describes it as a “tour de force of etching [that] veers toward total abstraction in its rendering of the fury of the bullfight”.[v] In this heavily worked and oversized etching, Picasso conveys anguish, chaos, fury, violence, and death. The jumbled limbs, overwhelming detail, overlapping elements, and energetic vectors that cut through the swirling composition add up to a level of intense visual stimulation that threatens to overload the viewer’s senses. Thus we struggle, like the figures in the image, to make sense of the scene.

Even with careful study it is difficult to entirely sort out the figures in the central vortex of this image. There seem to be at least four: a matador at left, a bull at center, a twisted female toreador above the bull, and a horse upon which she rides at right. The bull, whose impassioned charge is indicated by clouds of dust below his hooves, snorts in a rage as he lunges for the horse, who responds by standing on her hind legs with an expression of rage and aggression. The female toreador at center, who resembles Marie-Thérèse, seems a victim of the situation—she has been thrown from her mount and her body twists throughout the composition as if caught up in a whirlwind. Her breasts are exposed and her neck is bent in an unnatural and perhaps fatal position. The matador, running and raising his arms, and the faceted angular lines at left, which resemble broken glass, add to the general drama and intensity of the scene. Behind the central figures are several spectators sitting in the arena, including one at the far right that is clearly a representation of Marie-Thérèse—she stands out as an aloof and calm presence amidst the chaos and violence. From her forehead begins a javelin that strongly divides the composition in a diagonal, ending between the shoulder blades of the bull. As the weapon would have been used by the mounted female toreador at center, a connection is implied to both representations of Marie-Thérèse. Likewise, its role in the demise of the bull underscores the lovely young woman’s role in the demise of her lover. Picasso’s two representations of her also suggest conflicting roles: indifferent observer, innocent victim of circumstance, and perpetrator of mortal wounds.

Technically, this etching represents a magnificent level of achievement in line etching as well as perspective. In prints like this we can see how Picasso brings his iconoclastic approach to depth of field—which he began with his invention of Cubism with Georges Braque in 1907—to a new level. Abandoning traditional one- or two-point perspective, Picasso suggests depth in this composition through the sophisticated manipulation of line. By varying the tone and allowing selected elements to weave in and out of the composition, we have a sense of a foreground, middle ground, and background, though he freely plays with these zones by moving his figures in and out of them, changing the “proper” overlap of limbs and body parts, and distorting scale when it suits his purpose. As a result, the figures weave in and out of one another’s space in a dense and surreal world that more accurately conveys a sense of emotional intensity and chaos. Likewise, we feel almost suffocated by the intensity of the situation as we look. The entire plate is filled with a dense cover of figures in the backdrop of an arena —we have no sense of atmosphere or sky and there is no escape. All of this is accomplished with masterful control over the etching process—each line is distinct and clear.

Picasso anticipated the implosion of his personal life by several months, even a year. In July of 1935, Olga learned that Marie-Thérèse was pregnant and promptly left Picasso, taking their teenage son, Paulo. Picasso’s reputation in the bourgeois social circle he shared with Olga suffered a severe blow and he was anguished over the loss of his son. After a difficult legal process, Picasso and Olga determined to remain married but separated. The stress of these events caused him to give up making art for a period; he instead devoted his energies to writing surrealist poetry. In addition, Picasso’s interest in Marie-Thérèse waned once she was a mother, though he took care of her and their daughter Maya throughout his life. Picasso would later refer to this phase as the darkest period in his life.[vi] In etchings like Marie-Thérèse en femme torero (Bloch 220), it is almost as if he could clearly see the outcome ahead but was unable to stop it.

Like a number of prints from this period, including the Suite Vollard, the printing and publication of this etching is complicated. After a small number of proof impressions were taken in 1934 (signed), an edition of fifty on laid Montval was printed in April of 1939 by Roger Lacourière, a few months before death of Vollard (who was Picasso’s publisher). The unsigned edition was then purchased by Fabiani, Vollard’s protégé and executor, along with a number of other paintings and editions. Georges Bloch acquired a few impressions eventually and these were signed, but a majority of the impressions remained unsigned and were not released until Picasso’s death in 1973.

[i] A Picasso Portfolio: Prints from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010, 62.

[ii] A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-32 [New York: Random House Digital, 2007], 383.

[iii] See ibid., 492-3, 498-500.

[iv] See Baer, Picasso: Peintre-graveur, vol. II, 292, no. 425 and Wye, 63-6.

[v] MoMA, 67.

[vi] See Baer, Picasso the Engraver: Selections from the Musée Picasso, Paris [New York: Thames and Hudson and The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

1997], 41.