PABLO PICASSO

1933 (March 17 III, Paris)

Literature

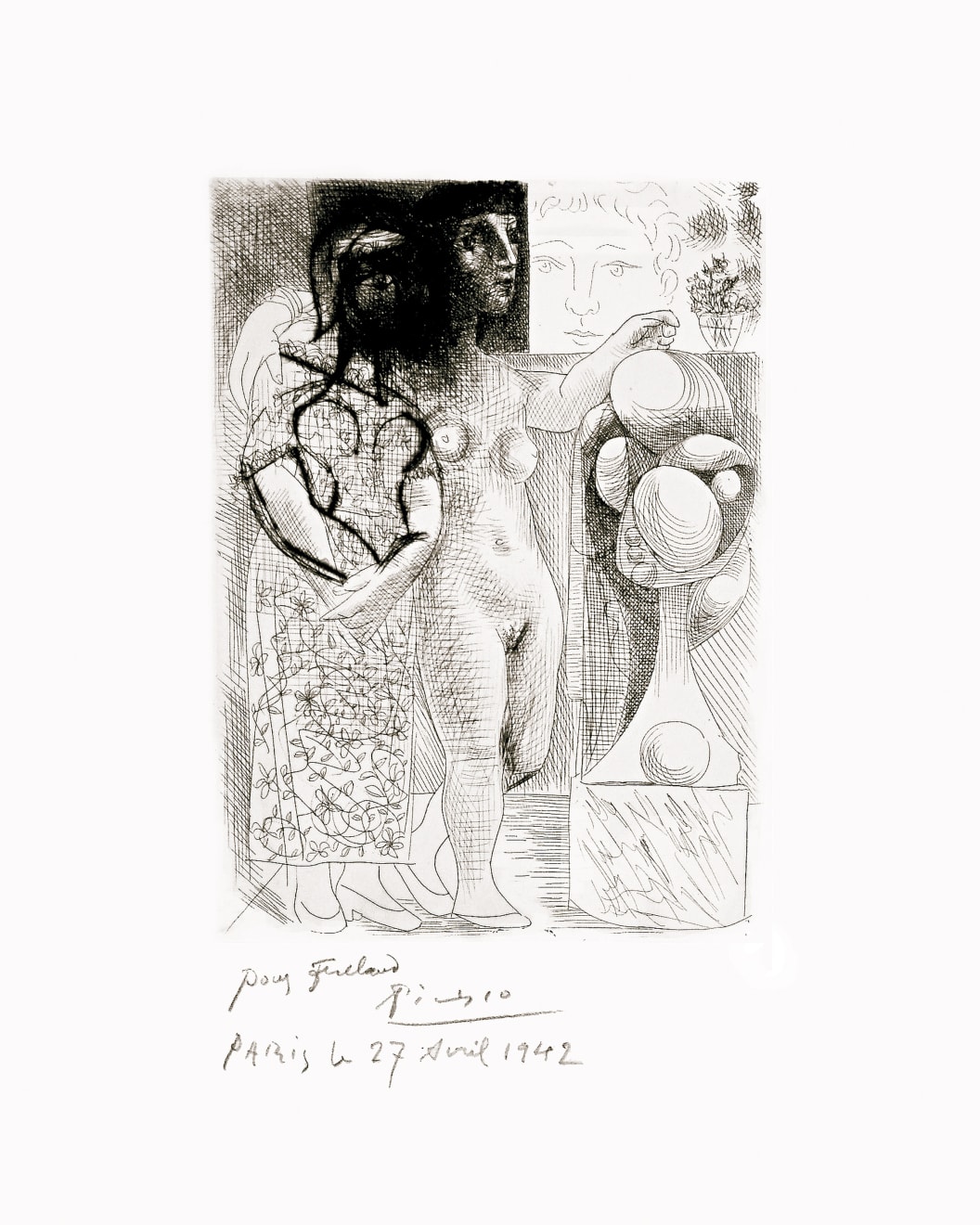

Marie-Thérèse Walter is known to have little understanding of Picasso’s art, and often complained that she could not see a likeness in his portraits of her. This dynamic appears in several prints of this period, both in the Suite Vollard and in individual plates such as this example. Here, a nude muse, who is somewhat bored of the situation, shows a puzzled Marie-Thérèse a sculpted head of herself. The two women in this image represent the dichotomy between Marie-Thérèse’s simple personality and her role as an inspiration for Picasso’s work. The artist peers in on the two of them with a somewhat concerned expression. Clearly, he is anxious that his young lover appreciate his homage to her.

In a direct relationship to the conflicted emotions expressed in the image, Picasso worked this plate quite heavily, both in etching and drypoint. The upper left quadrant is especially layered and dense; the etched crosshatching is enhanced with sumptuous drypoint details. This particular impression is a rare artist’s proof of the seventh (final state), one of only two or three printed by Lacourière in 1942 before the plate was steelfaced and editioned. As such, the drypoint burr is exceptionally rich. It is also dedicated to Jacques Frélaut, a printer in Lacourière’s studio who later became his most trusted intaglio printer: "Pour Frélaut, Paris le 27 Avril 1942" (Homme Façonnant un Arc Devant une Jeune Femme et un Flutiste, Bloch 305, 1938, has the same dedication). Presumably, he gave this impression to Frélaut in appreciation of his professionalism and patience—Picasso was notoriously demanding and exacting in the printmaking studio, but this did not bother Frélaut in the slightest. He and Picasso had a remarkable rapport. The noted scholar Pat Gilmour described Frélaut’s philosophy in relationship to Picasso thus:

Frélaut believed that to be a good printer, you need to grow up with a press so that you can work without tiring. He says the most dangerous thing for an artisan is skillfulness. A good collaborative printer needs an affinity for the artist, the facility that enables him to create the right atmosphere, and an ability to work “with joy.” Such a printer does not mind being manipulated: “The word manipulate, for me,” says Frélaut, “means almost an integration with the artist…I become him. He manipulates me.” From Frélaut’s point of view, Picasso was “simplicity, authenticity, and the opposite of convention” and his honesty in his work pervaded everything. Work was the only thing that was important to him, and in order to understand him, one only had to understand that. The artist always drew directly onto the copper, never from a prepared drawing, for engraving was a serious undertaking. He expected the printer to realize in the sheet what he had drawn in the plate, without tricks, but “frankly, with generosity and warmth.”i

This particular impression is a rare artist’s proof of the seventh (final) state, one of only two or three printed by Lacourière in 1942 before the plate was steelfaced and editioned. As such, the drypoint burr is exceptionally rich.

i As paraphrased by Pat Gilmour in “Picasso and His Printers,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter XVIII, no. 3 (July-August 1987): 85.