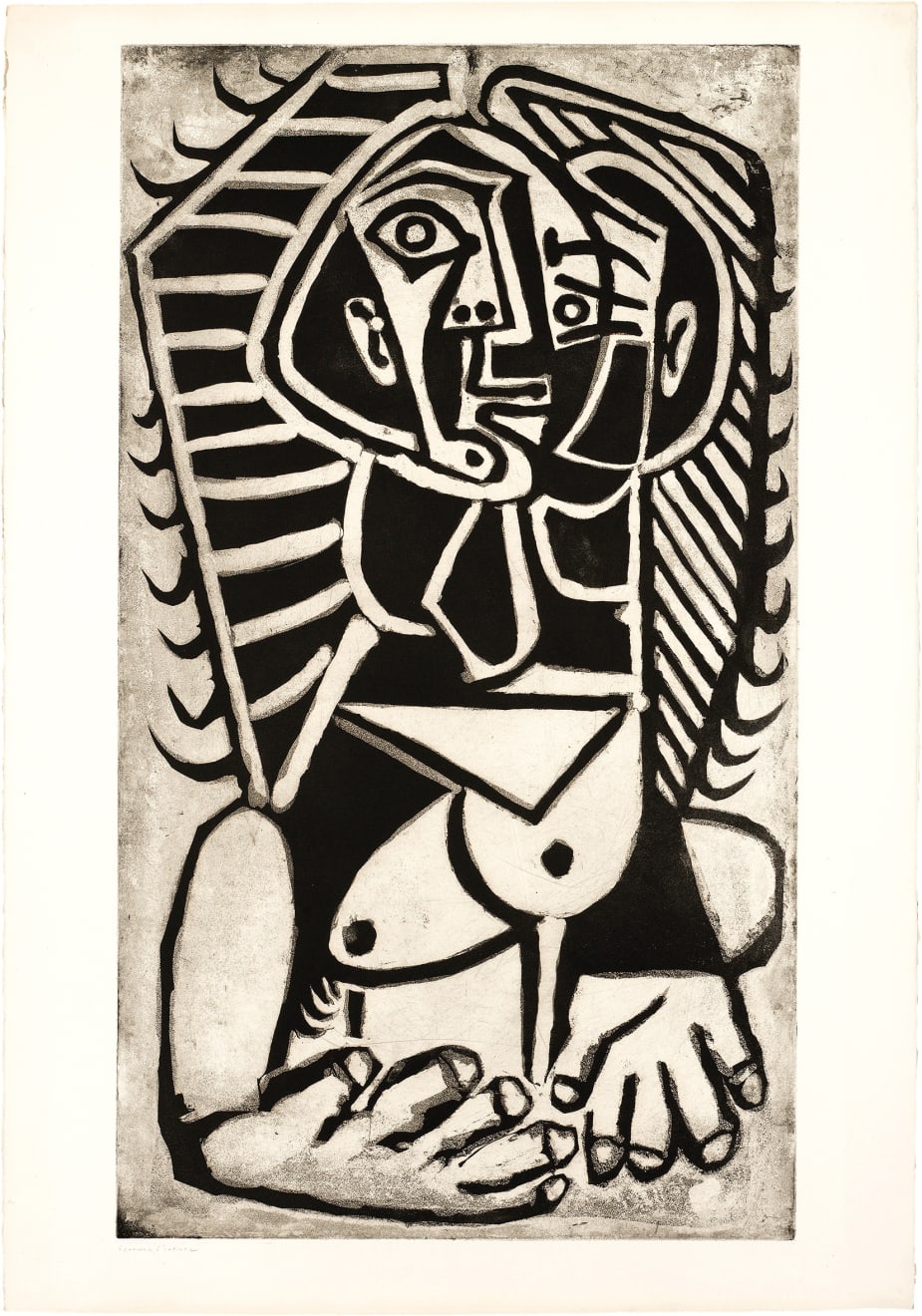

L'Égyptienne is among the most iconic of Picasso’s prints. The bold black-and-white composition is a stunning example of this phase of his career, characterized by an abstracted geometric approach to the figure; it is also a remarkable feat of technical brilliance. The sitter is shown in both frontal and profile positions simultaneously, lending a sense of conflict and drama to the portrait. While the subject is known to be Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s lover from 1943 to 1953, the work transcends its subject in its sheer graphic impact and compositional dynamism.

Picasso’s art and life are never entirely separable. This was one of the last portraits Picasso created of Françoise, at a time when their relationship was strained to a breaking point. Françoise had spent an extended period in Paris working on sets for a ballet. When Picasso etched this plate, she had recently returned to their home in Vallauris in the south of France. Her absence had infuriated Picasso; he poured his anger into this explosive image which is now known as L'Égyptienne. Françoise would leave him within a few months and would be the only woman to ever leave Picasso. With few exceptions, Picasso did not title his prints. L'Égyptienne was coined by Lacourière’s workshop in reference to the sitter’s hairstyle, which is reminiscent of Egyptian sarcophagi. Picasso was interested in Egyptian sculpture during its creation which, in addition to the aquatints lack of perspective and overt two-dimensionality most likely factored into the nickname as well.

In addition to its power as an image, L’Egyptienne is also remarkable from a technical standpoint. The print was created entirely with sugar-lift aquatint,* a technique that is among the most difficult to master in printmaking. The process is quite delicate and is easily thwarted at any stage—perfection is achieved only through experience and utter sensitivity to the materials. It is also quite challenging to achieve blacks as deep and even as they are here. Picasso had long been obsessed with the bottomless blacks of Rembrandt’s etching and had set a challenge for himself to equal them in his own work. As seen here, he had clearly achieved his goal. In addition, it is truly a marvel that he could do so on a plate of this size. The expansive and continuous areas of even black seen in this plate would elude event the most skillful printers—usually a flaw of some kind is inevitable.

The present impression is from the edition of fifty, inscribed by the hand of Marie Cuttoli on the reverse. Cuttoli was an important figure in the inner circles of the Parisian art scene; she was friends with Picasso and a number of other artists of the time, including Míro and Léger. A woman of great means who ran an influential boutique called Myrbor, she was instrumental in reviving the art of the hand-made textile, asking her artist friends to create designs that were executed by traditional weavers. These tapestries were produced to the highest standards in limited editions in Aubusson, France, and are now highly collectible.

*Sugar-lift aquatint: to create a sugar-lift, the artist paints on the copper plate with specially prepared sugar syrup that is allowed to dry. The plate is then coated with varnish or hard-ground and placed in a water bath. The sugar solution underneath dissolves and “lifts” the varnish or hard-ground, leaving the painted areas exposed. The plate is then put through the process of aquatint: it is dusted with rosin powder that is baked to the surface, and then etched to varying depths according to the desires of the artist; a full range of tones is possible.