PABLO PICASSO

Linocut rincé printed in cream with China Ink on Arches paper

Signed, dedicated and dated 'pour Norman Granz/ son ami Picasso/le. 18.5.69' upper right, in felt-tip pen

5 impressions pulled

Printed by Arnéra, 1963

Image: 25 ¼ x 20 7/8 inches

Sheet: 29 ¾ x 24 3/8 inches

Framed: 36 x 31 1/2 inches

(Baer 1245.C)

Literature

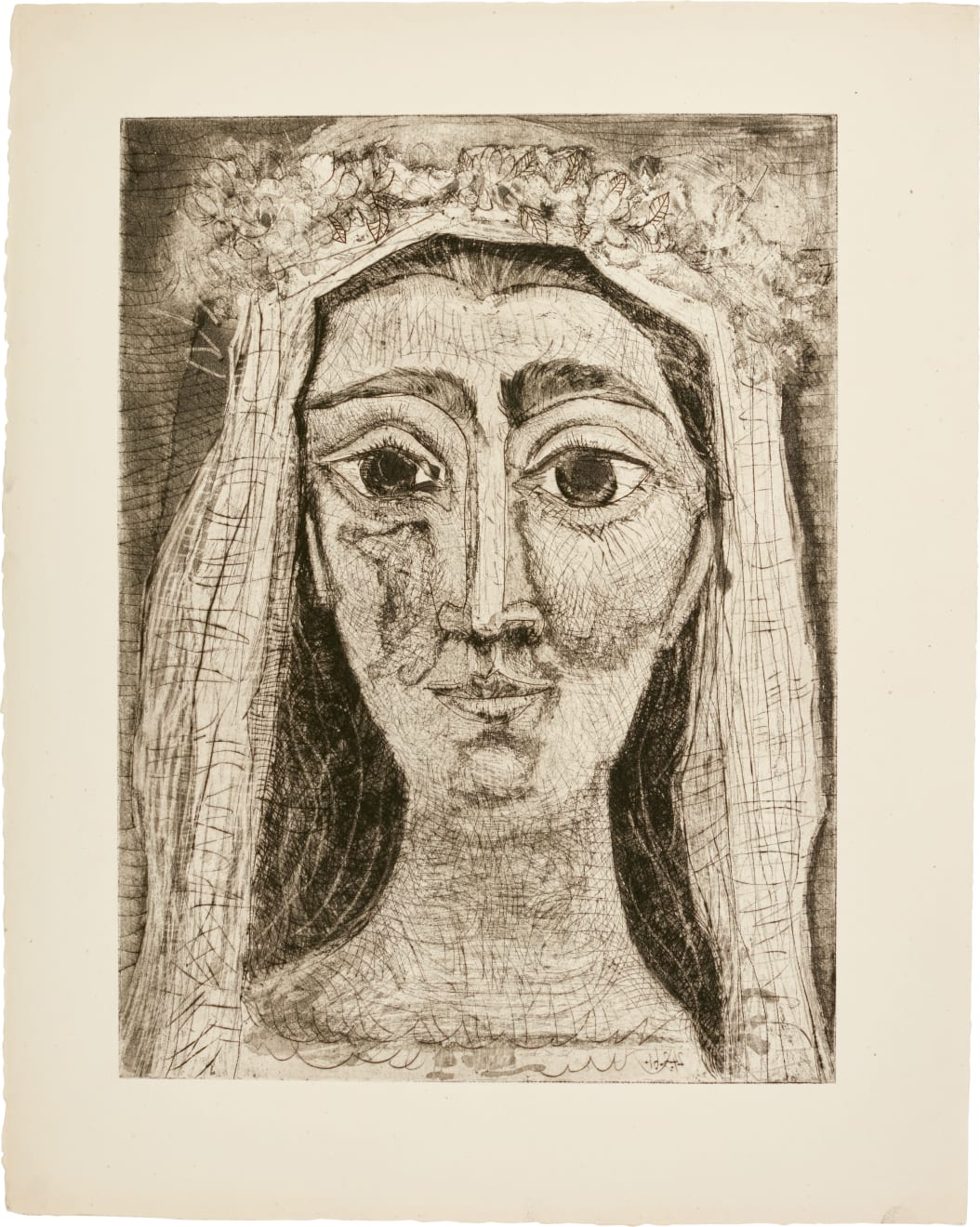

As its title indicates, this is a portrait of Picasso’s second wife Jacqueline Roque (1927-86) as a bride, created some three weeks after their marriage in Vallauris village hall. The couple had met in 1952, shortly after Roque (née Hutin) was employed by the Galerie Madoura in Cannes, the retail outlet for the Vallauris pottery atelier where Picasso was working with ceramics. An attractive young divorcée who had recently returned to France with her daughter Cathy after several years in West Africa as the wife of a colonial official, Jacqueline first appeared in Picasso’s work in several drawings of the painter and his model that he made in January 1954. The artist’s long-time friend and biographer John Richardson dates the beginning of what has become known as “l’époque Jacqueline” to September of that year, when she moved into Picasso’s rue des Augustins studio in Paris. From this moment onwards she was established as his last great muse and love, inspiring more works in the subsequent eighteen years of Picasso’s output than any of her predecessors ever had.

Given the significance of Jacqueline’s place in his life, it is entirely fitting that Picasso publicly acknowledged his love for her through the union of marriage. After his disastrous first marriage to the Russian ballerina Olga Kohklova, who tenaciously pursued him for decades after their separation until her death in 1955, and the bitterness of being left by his young mistress of ten years, Francoise Gilot, in 1953, the artist was understandably somewhat reluctant to tie the conjugal knot again until he felt absolutely secure with his new partner. Returning to Cannes shortly after Kohklova’s death, Roque and Picasso moved into an art deco villa, La Californie, where they lived harmoniously together until building works in the area forced a change. As Richardson recounts: “on 2 March 1961, Picasso and Jacqueline celebrated their marriage in great secrecy and, in June, installed themselves in a handsome, well-protected villa idyllically set on a terraced hillside near Mougins. A former mas, the house had been transformed before the war into a luxurious villa … named after a neighbouring pilgrimage chapel, Notre-Dame-de-Vie, and this no doubt commended it to someone whose eightieth birthday was about to be celebrated, and whose greatest fear was death. The house lived up to its auspicious name. Picasso spent the last twelve years of his life there, working on what amounted to … a phenomenal finale to a phenomenal oeuvre.” (John Richardson, “L’Epoque Jacqueline”, in Late Picasso: Paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints 1953-1972, Tate Gallery, London 1988, p.23.)

In his many depictions of Jacqueline, Picasso almost always showed her viewed from the side, emphasizing her elegant long-nosed profile and submissive pose that reminded him of an oriental odalisque. Here, perhaps more fittingly for a marriage portrait, he emphasizes her large and brilliant dark eyes. He had first attempted to portray her from the side, but after two unsatisfactory tries (Ba 1087 and Ba 1088) he decided to portray her from the front. This full-frontal view, which recalls the portrayal of the holy mother Mary in a traditional church icon – replacing the Madonna’s shawl with a bridal veil and her halo with garland of wedding blossom – emphasizes the near-religious iconic status of Jacqueline in Picasso’s life. After enumerating the countless ways in which she was indispensable to the artist in his last years – in her many roles as interpreter, secretary, agent, cook, poet, driver, nurse, photographer, model as well as guard and protector, sheltering him from the many assaults from the outside world – Richardson concludes that: “for Picasso, Jacqueline was, in a very literal way, Notre-Dame-de-Vie” (ibid, p.47).

Perhaps in homage to the woman who was already so much to him, Picasso took his sugar-lift aquatint and drypoint Jacqueline en mariée, de face. I through no fewer than eighteen states, all on a single day. No edition was ever created of this print, but a small number of proofs were taken of every state. After sketching his composition using a brush and sugar-water, creating a watercolor effect with varying shades of grey, and adding a few linear details with the point of the scraper, Picasso bit the plate with acid by hand. This resulted in delicate white marks in the grey areas of the neck, the left side of the face and in the shadows on either side of Jacqueline’s neck and face as well as a fine white line that delineates the left edge of her veil. In the subsequent seventeen states, Picasso worked this composition obsessively, deepening the shadows behind Jacqueline’s face and neck so that they seem eventually to become her black hair. Experimenting with the shadow on the left side, he alternately darkens it, removes it and returns it again. At the same time he plays with the definition of Jacqueline’s neck and facial features and their flattening or remodeling in three-dimensions, while the detail of her veil and bridal blossom become increasingly defined.

Writing of Picasso’s habit of working in series, which he compares to the technique of the nineteenth century French painter Jean-August-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), Richardson explains that for Picasso, “in finishing a work you kill it” (quoted in ibid, p.37). For the artist, “almost always the first in any series” was his personal preference, “and then the penultimate one, the one that was still open-ended, before the coup de grâce” (ibid). Our impression is from the first state of Jacqueline en mariée, de face. I, and thus shows the image at its simplest and purest, at its closest to Picasso’s original gesture. It is one of only five proofs pulled by Jacques Frélaut in Paris in this state, and is the only impression printed on vellum.