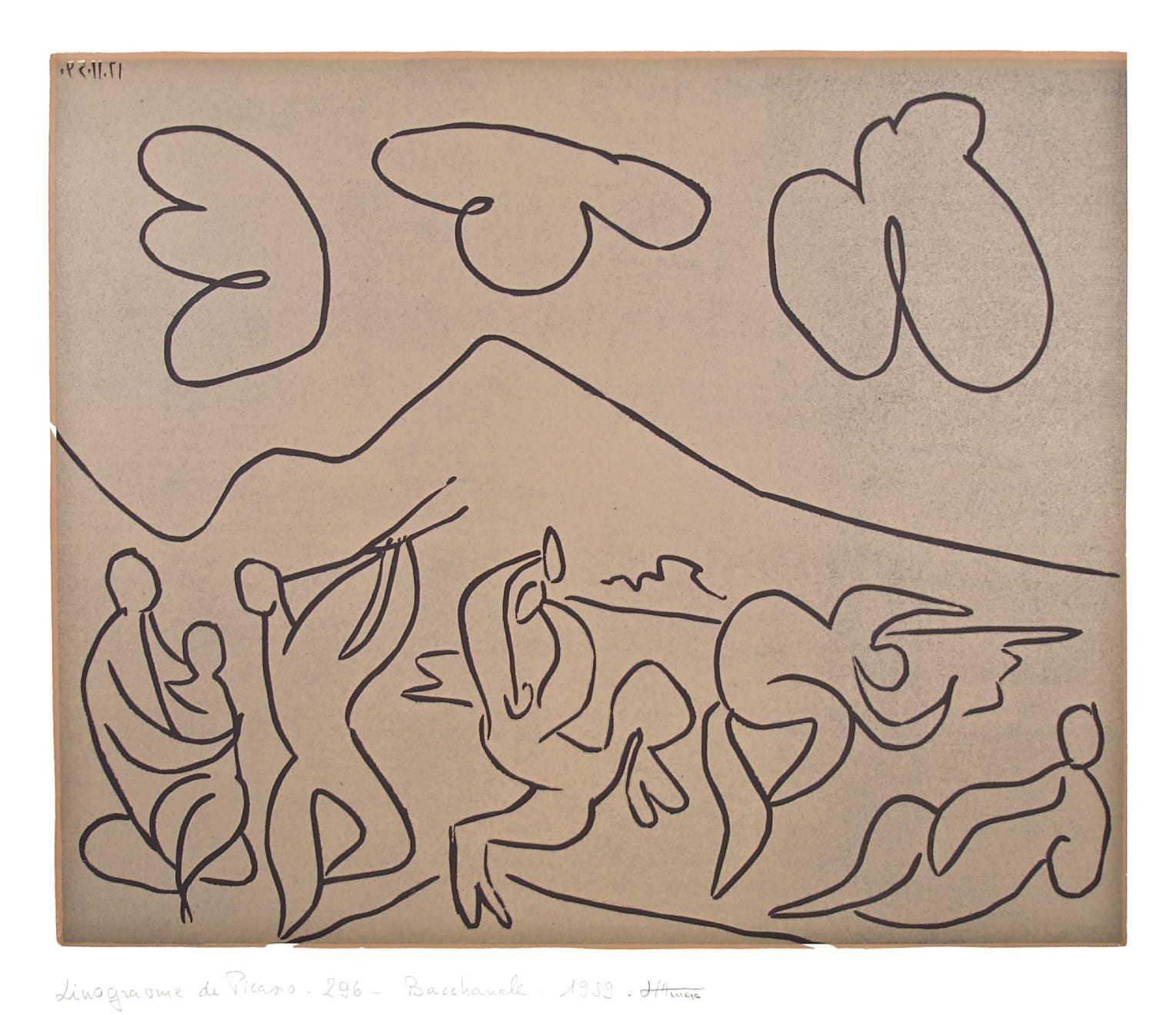

PABLO PICASSO

Linocut printed in dark tan ink on a solid black background on Arches wove with Arches watermark

One of five artist's proofs outside the edition of 50

Inscribed "Linogravure de Picasso - 296 - Bacchanale - 1959. H. Arnéra" in pencil, lower left; "F11599" in pencil, verso

Printed by Arnéra, 1960

Published by Galerie Louise Leiris, 1960

Image: 21 x 25 1/4 inches

Sheet: 24 1/2 x 29 5/8 inches

Framed: 30 5/16 x 36 5/16 inches

(Bloch 927) (Baer 1255.A)

Literature

Bacchanale was created during a period of great contentment in the Picasso’s life. In summer 1955 he had moved to La Californie, a great fin-de-siècle villa in the hills above Cannes, with his new partner Jacqueline Roque, an attractive woman forty-five years his junior whose elegant, exotic profile and large, brilliant, dark eyes inspired a fresh phase of creative productivity in the artist. As was usual for Picasso, a new relationship sparked a foray into an as yet under-explored printing technique. This time it was linocut. Since his relocation to the south of France in 1948, Picasso had become increasingly frustrated by the length of time it took for his etching and lithographic plates to travel to and from his printers in Paris, and thus he found local printer, Hidalgo Arnéra, who specialized in printing newspapers and posters in the town of Vallauris. In 1951 when Picasso was invited to create a poster to advertise the town’s annual art exhibition, Arnéra suggested that he use linocut, which is relatively easy to cut and print and can easily accommodate text, making it ideal for poster design. Following Arnéra’s advice, Picasso went on to create a series of linocut posters during the 1950s and early 1960s, advertising the local arts and crafts exhibitions and bullfights.

Picasso’s first independent linocut was Portrait of a Young Girl, after Cranach the Younger, made in 1958. Although he had learnt quickly from Arnéra and was now technically proficient, the artist found the process of making this multi-colored print in linocut fiddly and time-consuming: he had to cut as many linoleum blocks as there are colors in the print, ensuring that they all registered correctly. Adapting these new-learned techniques, he began to work in a revolutionary process of reduction. Rather than cutting many separate pieces of linoleum, he used a single piece, which he cut, printed, then re-cut and re-printed, just as he reworked his etching and lithography plates. Arnéra recounts that during this period of intensive interest and experimentation, Picasso would cut the linocuts late at night, and his chauffeur would drive them to the workshop early the next morning. Arnéra would print them before lunch-time (a demanding task as the inks had to be mixed in a particular way so that the different colors overprinted properly) and then take the prints to Picasso for viewing at 1:30pm precisely. He did this every weekday for eight years, resulting in around two hundred linocuts.i

Saturated with the Mediterranean sun and the pleasures it brought with it—the bullfights, the beach, and the intense warmth and light—in the mid 1950s Picasso renewed an earlier interest in some of the classical motifs that he associated with the region—particularly the theme of the Bacchanale. Mythical characters first appeared in his work during his neo-classical period after the First World War, and he returned to them for a period during the early 1930s under the influence of Surrealism. Ten years later, even as the war raged around Paris, in 1944 he was working on an adaptation of Poussin’s Bacchanal 1628 (Louvre Museum, Paris), reflecting his longing perhaps for the arcadian pleasures it represents. In his many images of the theme created after his return to the south in 1945, the fauns, satyrs, and dancing figures that he associated with ancient Greece abound. The figure of the piper or flutist has a special significance in providing the music to which the participants move. Picasso created numerous representations of him playing the diaule or double-flute, both in combination with other figures, and alone. The flutist features as a horned faun in a series of etchings created in 1945 that begins with Faune flûtiste et danseuse à la maraca et au tambourin (Bloch 1341), as a more simplified and stylized figure on numerous ceramic plates from 1947 onwardsii, and as a neo-classical boy, sometimes wearing a laurel wreath, in drawings, and ceramic sculptures and cardboard and/or metal cut-outs from the mid 1950s, such as Joueur de diaule 1954-5 and Musicien assis 1956iii. His ubiquitous presence in Picasso’s depictions of revelry may reflect the importance of music for the artist in the events.

In November and December 1959, Picasso created several linocut versions of the theme depicted in Bacchanale in one, two, four and seven colors, including Bacchanale with Owl, Bacchanale with Acrobat and Fauns and Goat. In all these scenes of celebration, the piper is seated, supplying the melodic basis for the rhythm marked by the clash of the dancers’ cymbals, while an owl, a bull and a goat witness the revelers’ antics. By contrast, in this version of the Bacchanale, the piper is dancing with two other participants, while the scene is witnessed by a reclining figure on the right and a mother and child on the left side. Following these linocuts, Picasso went on to create two further similar compositions using the lithographic medium in early December, both of which feature the flutist on the left side of the image, and a leaping figure with cymbals as in the linocut, and are drawn in the same extremely simplified curving line, in which figure flows sensuously into abstraction.

This impression is one of four artist’s proofs printed in tan on a solid black background on Arches wove by Arnéra in 1960. It was annotated by Arnéra: ‘Linogravure de Picasso - 296 - Bacchanale - 1959. H. Arnéra’ at the lower left, in pencil. There was also a signed and numbered edition of fifty printed by Arnéra in 1960, and published by Louise Leiris Gallery, Paris, in the same year.

i Hidalgo Arnéra quoted in Patrick Elliott, Picasso on Paper, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2007, p.21.

ii John Richardson, Picasso: The Mediterranean Years 1945-1962, Gagosian Gallery, New York 2010, pp.236-7.

iii ibid, pp.223-7, 231-3 and 234-5.