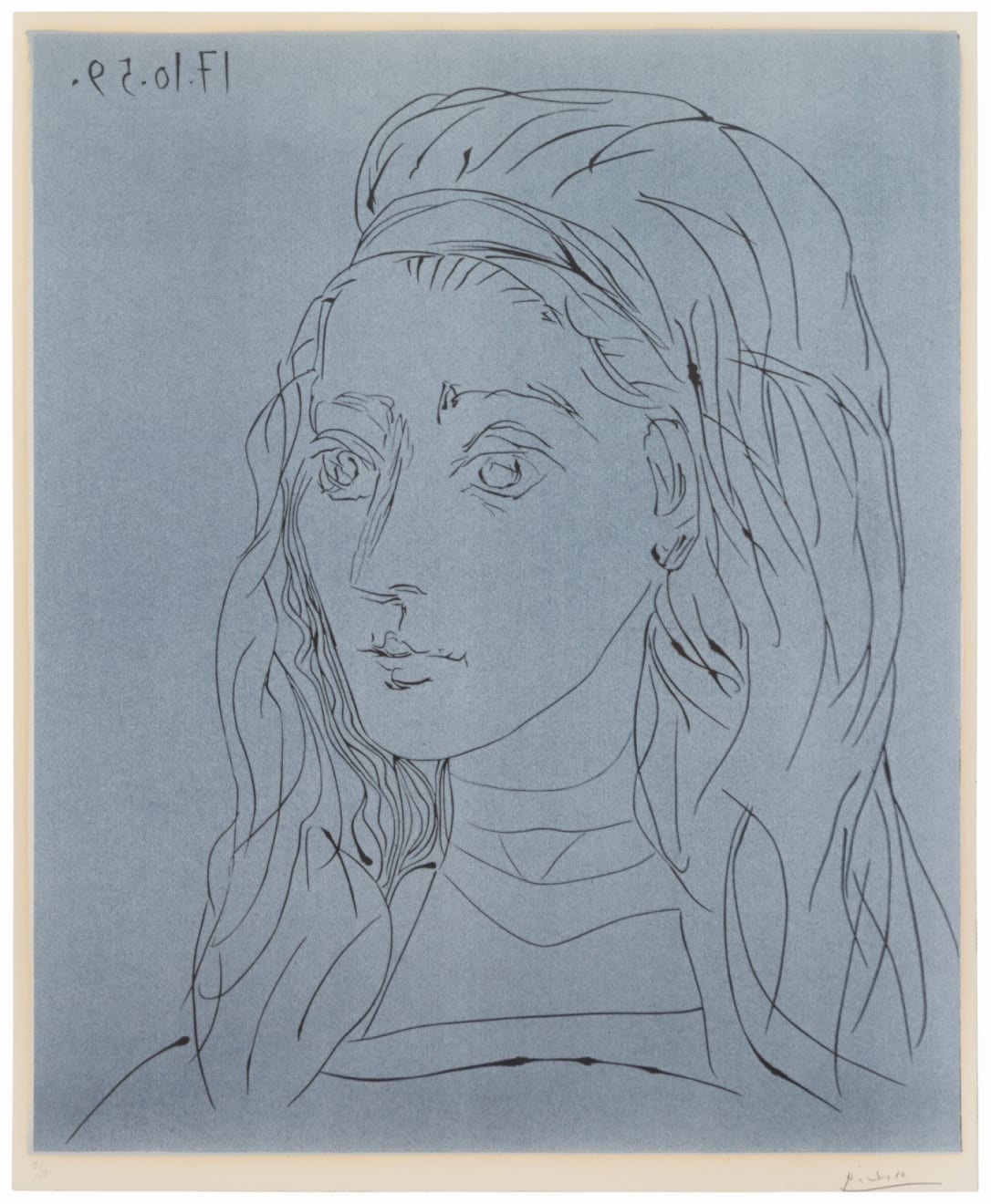

PABLO PICASSO

Linocut printed in two colors on Arches wove

Signed by artist lower right, in pencil

From the edition of 50

Printed by Arnéra, 1959-60

Published by Galerie Louise Leiris, 1960

Image: 25 x 20 7/8 inches

Sheet: 29 1/2 x 24 1/2 inches

Framed: 36 3/8 x 31 7/8 inches

(Bloch 923; Baer 1245.B.a)

Literature

Created during a period of great contentment during Picasso’s life, this print is a loving portrait of his last great muse, and eventual second wife, Jacqueline Roque (1927-86). It is also one of his first linocut portraits of Jacqueline, whose image dominates his late work—his linocuts and lithographs in particular—representing a significant period within his œuvre. The couple met in the summer of 1952 and by 1954 were living together, first in Picasso’s rue des Grands-Augustins studio and then in a villa called La Californie in the hills overlooking Cannes from 1955. Jacqueline’s large, brilliant dark eyes and elegant, straight-nosed profile feature repeatedly in lithographic portraits that Picasso created in 1957 and 1958, as the artist celebrated his new love. But it was in the medium of linocut that Picasso was to open up the most dramatically creative new ground over the subsequent years.

Like his earlier productive collaborative relationships with the master printers Roger Lacourière (1892-1966) and Fernand Mourlot (1895-1988), Picasso’s experimental foray into the medium of linocut was in part stimulated by his new love interest. He had met Hidalgo Arnéra (1922-2007), who specialized in printing newspapers and posters, not long after relocating to the town of Vallauris on the Côte d’Azur from Paris at the end of the 1940s. In 1951, when Picasso was invited to create a poster to advertise the town’s annual art exhibition, Arnéra suggested that he use linocut, which is relatively easy to cut and print and can easily accommodate text, making it ideal for poster design. Following Arnéra’s advice, Picasso went on to create a series of linocut posters in the early and mid 1950s, advertising local art exhibitions and bullfights in which he explored the graphic potential of the medium for producing dramatic and eye-catching images. The artist’s first independent linocut was Portrait of a Young Girl, after Cranach the Younger, made in 1958. Following this, Jacqueline’s famously exotic profile quickly appeared on his linoleum blocks. A master of linear reduction, Picasso discovered that linocut perfectly suited his desire to pare his images down to their most powerful and simplified form. Ever since his academic training at the end of the previous century, the artist had been combining his technical mastery of classical methods with a free use of his imagination and invention. During his years of radical innovation in the language of representation in the early decades of the twentieth century, Picasso continued his habit of making more traditional forms of drawing, maintaining countless sketchbooks with an almost diaristic function. Developing his own personal style, Picasso fused the graphic technique of refining an image to bold elemental line that he had learned working as an illustrator in the 1900s with an expressionism he had adapted through his interest in primitivism. The forms of this iconic language in which naturalism and stylization blend seamlessly are visible in this Portrait de Jacqueline, in which the lines of her thick cascading locks turn to patterning in the area behind her right cheek, and the volume of her face and head emerge above the flat plane of her neck. The artist was particularly fond of his lover wearing her hair loose, pulled back to frame her face by a headband, as is demonstrated in numerous linocut portraits of her made in the early 1960s. In this portrait, Jacqueline is depicted with extraordinary sensitivity, given the somewhat non agile medium of linocut—by comparison with etching and lithography—in which the artist must carve the lines of his image from a linoleum block. As always, Picasso fearlessly pushed his medium to extremities, breaking all the technical rules. The delicate lines of Jacqueline’s face and hair appear drawn with a pen and ink rather cut from linoleum and printed. They are enhanced by the colored background of the paper, the soft blue accentuating the subject’s youth and gentle character.