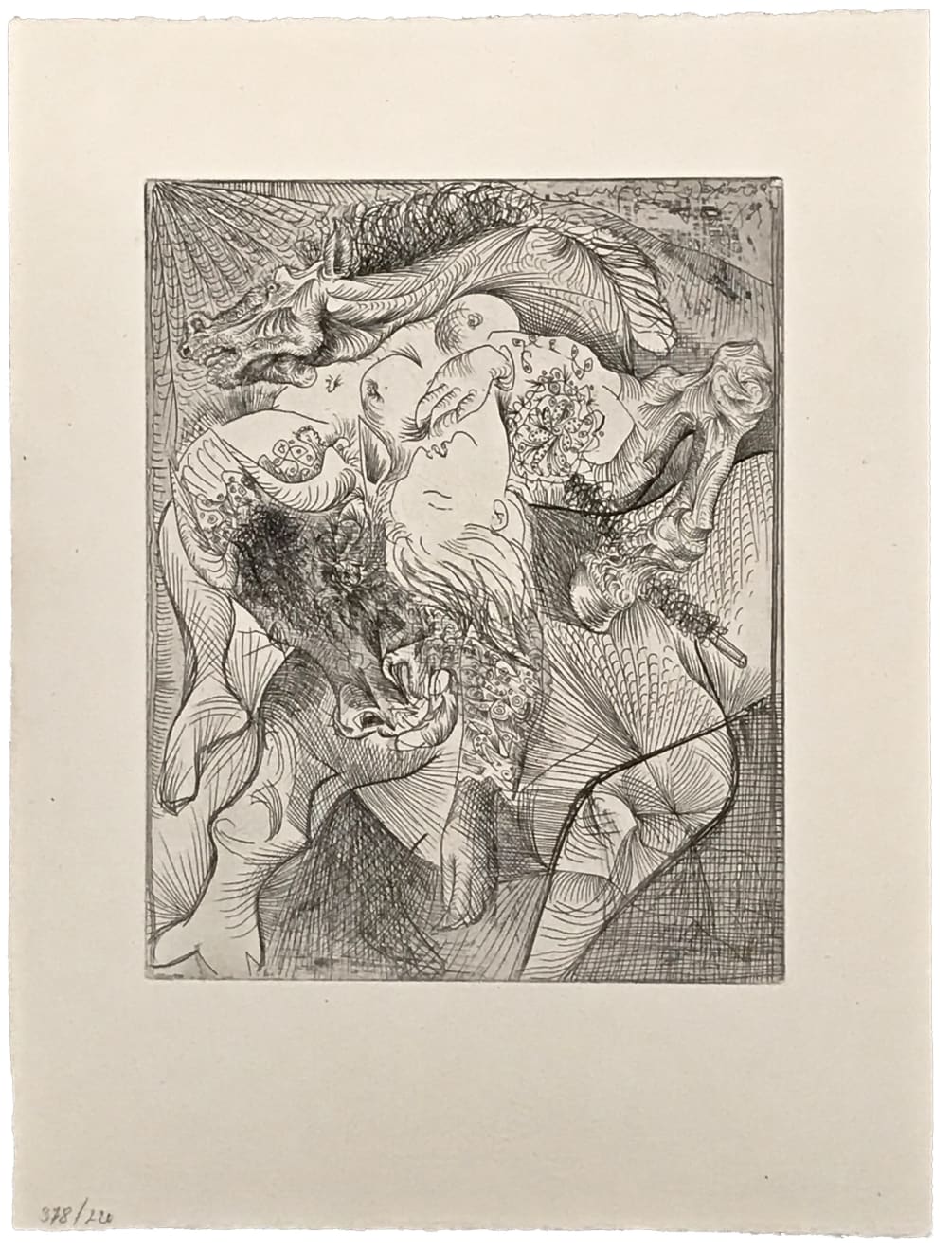

PABLO PICASSO

Etching on Montval laid paper with Picasso watermark

From the edition of 260

Inscribed "378/220" in pencil, lower left

Inscribed "496096" in pencil, lower right verso

Petiet Estate stamp on verso

Printed by Lacourière, 1939

Published by Vollard, 1939

Image: 11 5/8 x 9 1/4 inches

Sheet: 17 5/8 x 13 5/16 inches

Framed: 24 3/8 x 21 5/8 inches

(Bloch 220) (Baer 426)

Literature

In Femme Torero (Bloch 1329), Picasso plays out the terrible emotional and social complexity of his personal life in a grand allegory of the bullfight. The jumbled limbs, lack of traditional perspective, intricate detail, dazzling linear patterns, and energetic vectors that cut through this swirling composition add up to a level of intense visual stimulation that threatens to overload the viewer’s senses. The struggle of the figures mirrors the viewer’s own frustrated effort to make sense of the scene, which, like a clever illusion, never connects logically.

In 1934, Picasso was in his mid-50s and was likely experiencing a sort of mid-life crisis. His relationship with his wife, Olga Khokhlova—a former ballet dancer from Ukraine—was extremely strained and had been so for years. Though a striking beauty in her youth, she was now somewhat ravaged by years of health problems, poor diet, anxiety attacks, and obsessive coffee-drinking. Meanwhile, his long-term liaison with his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, was beginning to disintegrate and she would soon reveal to him that she was pregnant (according to Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer, it was just before Christmas of 1934). Though Picasso biographer John Richardson suggests that Olga may have been aware of the affair as early as 1929 and had come to accept it, the truce was tenuous and Picasso feared that his wife’s wrath could descend at any moment. [i] In addition to his romantic entanglements, Picasso had been struggling with self-doubt as a result of mixed critical responses to his mid-career retrospectives in Paris and Zurich in 1932.[ii]

The stress of Picasso’s situation comes through strongly in his bullfight prints of the time. Each reflects a slightly different emotional landscape through both narrative and style, but the players are the same. Picasso used the figure of the bull to represent himself, while the female toreador—who traditionally rides on horseback for protection—represents Marie-Thérèse. The horse stands for his wife Olga.[iii] In Marie-Thérèse en femme torero, the bull’s expression is one of frustration and anger—the fragmented and chaotic composition is enhanced with intense hatch marks and linear patterns that intensify the effect. Marie-Thérèse’s face is the only area that is devoid of decoration. Her lily-white skin draws our eye to the center of the composition. The swooning expression on her face and her exposed breasts emphasize her role as Picasso’s lover. She seems a victim of the situation—her body twists throughout the composition as if caught up in a whirlwind. At upper left, the horse strains in a panic. The “painful triangle” of this relationship is literally reflected in the composition, which is built upon a three-sided form within a vortex.[iv] The forelegs of the bull form the base and it culminates in the right breast of the torera. It appears that with this and related etchings, Picasso anticipated the implosion of his personal life by several months, even a year. In July of 1935, Olga learned that Marie-Thérèse was pregnant and promptly left Picasso, taking their teenage son, Paulo. Picasso’s reputation in the bourgeois social circle he shared with Olga suffered a severe blow and he was anguished over the loss of his son. After a difficult legal process, Picasso and Olga determined to remain married but separated. In addition, Picasso’s interest in Marie-Thérèse waned once she was a mother, though he took care of her and their daughter Maya throughout his life. Picasso would later refer to this phase as the darkest period in his life.[v]

The current impression is from the edition of 260 printed on Montval laid paper watermarked “Vollard.” It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard estate.

[i] A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917-32 [New York: Random House Digital, 2007], 383.

[ii] See ibid., 492-3, 498-500.

[iii] See Bernhard Geiser and Brigitte Baer, rev., Picasso peintre-graveur, vol. 2 [Bern: Editions Kornfeld, 1990-2], 292; and Deborah Wye, A Picasso

Portfolio: Prints from The Museum of Modern Art [New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2010], 63-6.

[iv] Wye, A Picasso Portfolio, 65.

[v] See Baer, Picasso the Engraver: Selections from the Musée Picasso, Paris [New York: Thames and Hudson and The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

1997], 41