PABLO PICASSO

Literature

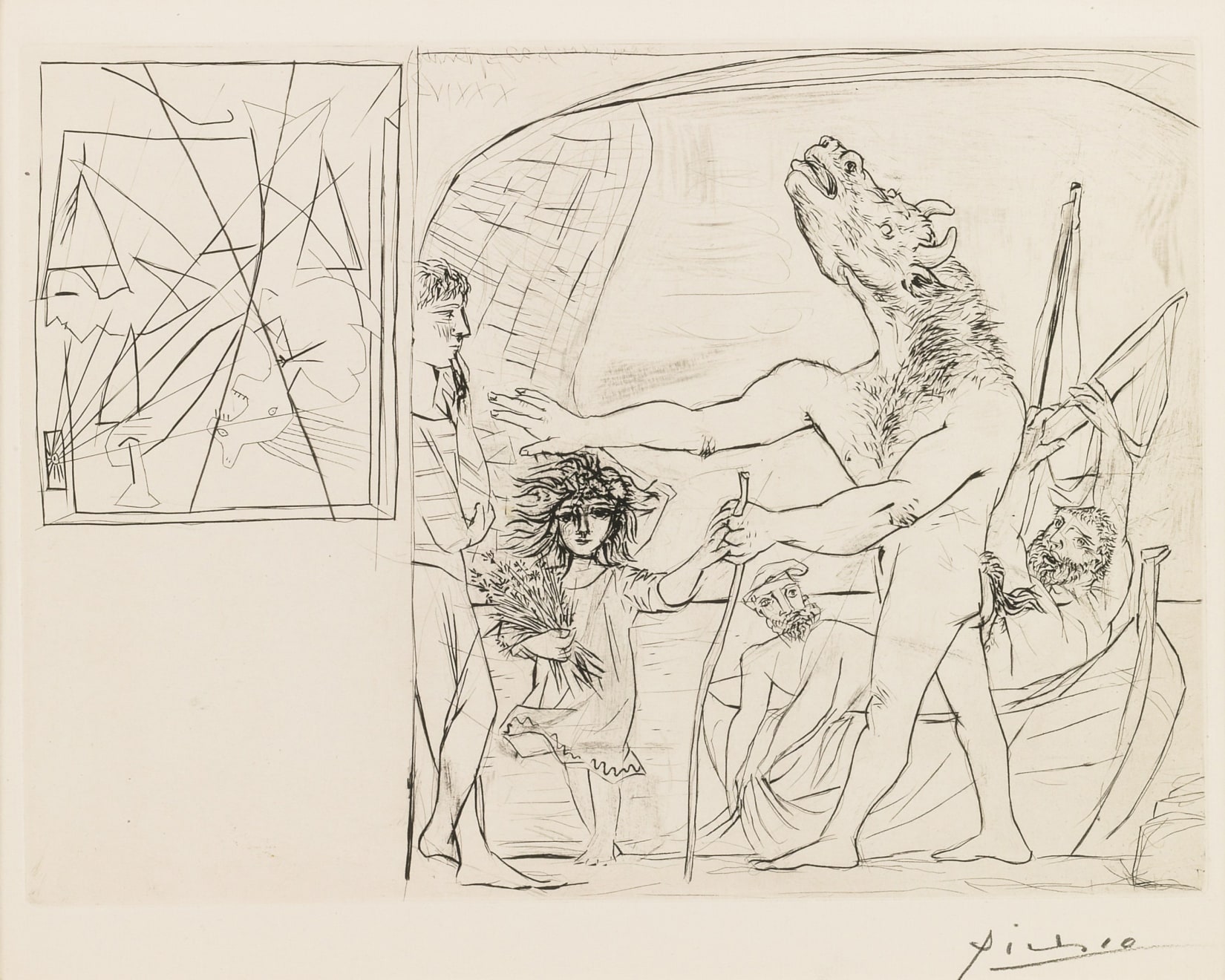

This plate is Picasso’s initial foray into the theme of the Blind Minotaur. Interestingly, he chose to work on a plate with which he had already worked a few months earlier—at the upper left is an inverted image of the Death of Marat (Bloch 282) that Picasso had originally produced to accompany a book of poems by the surrealist Benjamin Péret. His decision to reuse this image as a foundation for the Blind Minotaur was likely a careful one, as the subject of the smaller image relates symbolically to the overall theme. Marat was one of the most important political figures in the French Revolution and his fiery journalism and public speeches incited the masses to action. He was stabbed in the heart while bathing by the royalist sympathizer and aristocrat Charlotte Corday, who had requested audience with him under the pretense of providing information about protest activities in the north of France. Picasso shows Corday as a beastly creature swept up in a rage, plunging her kitchen knife into Marat’s chest, his body already draped over the edge of the bathtub in death.

In her analysis of this plate, art historian Lisa Florman argues that Picasso’s representation of the political martyr’s death was most likely inspired by Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 treatment of the same subject, which many historians cite as the first Modern painting.i David was a friend and follower of Marat, and his now famous canvas memorializes the journalist in a manner that had been previously reserved for religious figures—at the time, a radical move. The conventions of academic painting, which regulated the visual arts, confined images of secular figures to portraiture, and David’s image opened the gates for artists to paint heroic scenes of contemporary figures. As previously noted, Picasso’s interest in David’s painting was likely purely symbolic. Picasso scholar Brigitte Baer points out that the Marat figure closely resembles his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter and scholars have thus interpreted the violently enraged murderess as his wife Olga Khokhlova.ii If so, the image is symbolic of Picasso’s worst fears regarding possible outcomes for his indiscretion with Walter—perhaps his gesture of inverting and cancelling out the image was meant to banish the possibility, as he was a highly superstitious man. (This was in keeping with his Catalan upbringing, as noted in Françoise Gilot’s Life with Picasso [Virago Press, 1990, reprint of 1964 McGraw-Hill edition], 230-2).

Against this backdrop of violence and martyrdom Picasso begins his theme of the Blind Minotaur. Baer suggests that the Death of Marat scene, around which Picasso drew a frame, is like a broken mirror toward which “his love for Marie-Thérèse…is leading him on blindly”.iii The fishermen, who are clearly alarmed, seem powerless to stop him. The young sailor at left, whom scholars have interpreted to represent the artist as a young man, watches passively as the middle-aged Minotaur marches toward his destruction at the hands of the innocent young girl with a bouquet of flowers (Marie-Thérèse).

It is interesting to note that Picasso built this image painstakingly—after sketching the initial foundation in drypoint, he engraved the dark lines with a burin—a slow and technical process. Because he was working from his personal studio in Boisegeloup, he printed the proofs himself and burnished lines as required (these leave a ghostly mark that provide depth to the negative areas of the composition). In all, he changed the plate twelve times before settling on this final version.iv This carefully composed image—among the few engravings he created in his career—sets the standard for the three Blind Minotaur images to come. He changes the technical approach, rearranges some of the figures and changes details, but the basic components are in place.

The current impression is from the edition of 260 printed on Montval laid paper watermarked “Vollard” and “Picasso”. (There was also an edition of fifty with wide margins and a separate watermark, and a small edition of three.) It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard estate.

i Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso’s Classical Prints of the 1930s. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2000, 152-3.

ii Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection, Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, 87.

iii Picasso the Printmaker: Graphics from the Marina Picasso Collection, Dallas Museum of Art, 1983, 91.

iv See Brigitte Baer, Picasso the Engraver: Selections from the Musée Picasso, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997, 71.