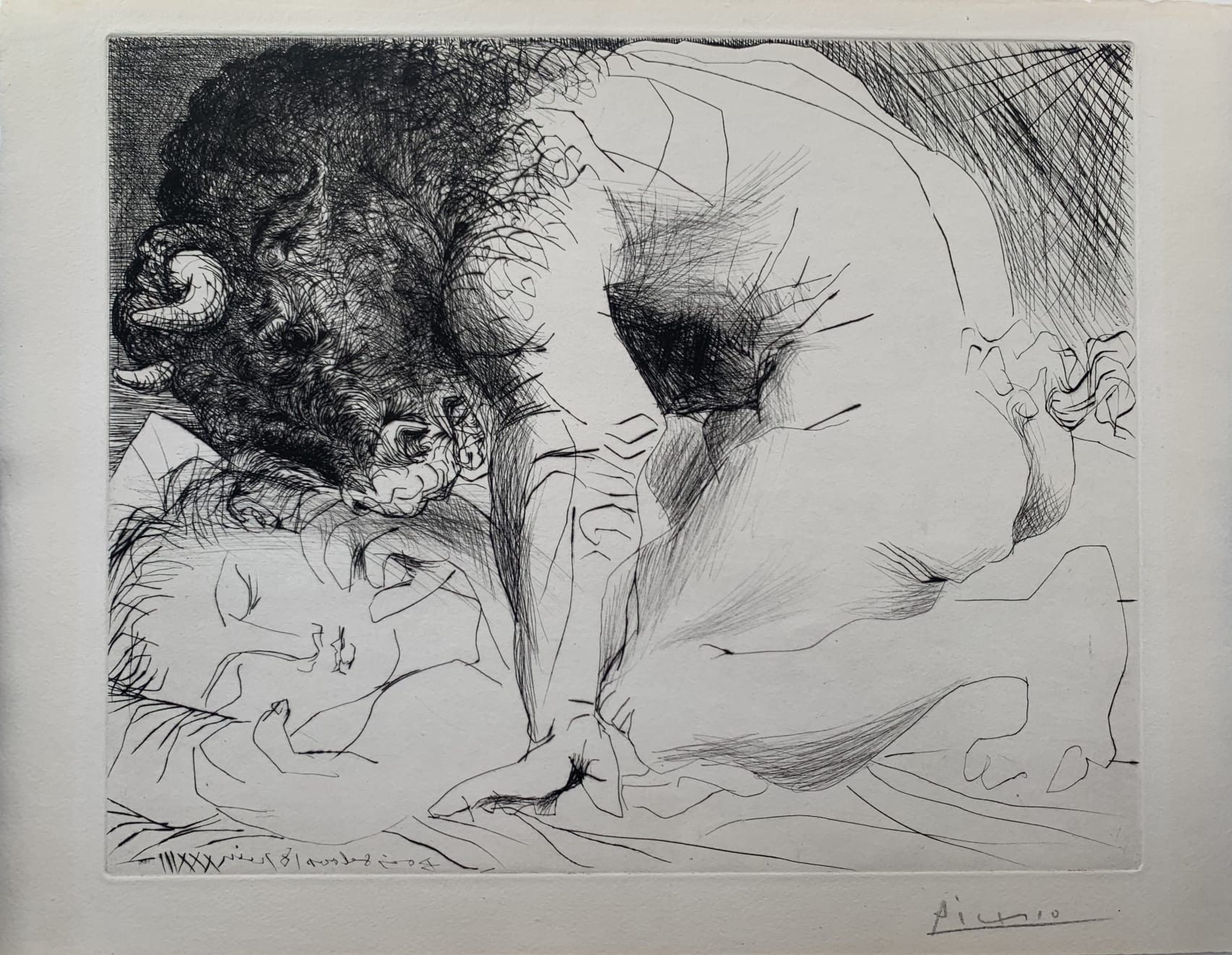

PABLO PICASSO

Drypoint printed on Montval laid paper with Vollard watermark

From the Suite Vollard (S.V. 93), edition of 260 of the second (final) state

Signed by the artist in pencil, lower right

Printed by Lacourière, 1939

Published by Vollard, 1939

Image: 11 3/4 x 14 3/8 inches

Sheet: 13 3/8 x 17 3/4 inches

(Bloch 201) (Baer 369.II.B.d)

Literature

This is among the most powerful and emotionally evocative prints of the Suite Vollard. In this plate, the Minotaur is shown at his weakest and most vulnerable. As he tenderly caresses his sleeping lover, his contracted body and gasping mouth also suggest that he is pained. Interestingly, the beast is in a similar pose in Minotaure amoureux d’une femme-centaure (Bloch 195) and Minotaur blessé (Bloch 196) of the Suite. The connection between all three images suggests that the same passion that ignites the beast’s ardor results in suffering and his eventual downfall. Nearly a decade later, Picasso commented on this print when showing it to a subsequent lover: “He’s studying her, trying to read her thoughts…trying to decide whether she loves him because he’s a monster…It’s hard to say whether he wants to wake her or kill her”.i

Sleeping is a common motif in Picasso’s work of this period and he used it to signify a number of emotional states, including loneliness, bliss, and ignorance—all three in this case. His lover, dozing blissfully, is ignorant of her effect on him and of his internal conflict; the woman is clearly Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s mistress at the time. She is known to have been fond of naps, but perhaps more importantly, unable to appreciate or understand her lover’s art. The psychological and emotional divide between the Minotaur, who represents the artist, and the object of his affections, is implicit in the beast’s gesture and the fact that she does not respond.

Interestingly, a complimentary plate in the Minotaur series shows the Minotaur asleep while the lover stands watch over him (Marie-Thérèse, en Vestale, veillant le Minotaure endormi, Bloch 193). This image similarly suggests that Picasso’s attraction to Marie-Thérèse was overpowering, leaving him with a sense of entire reliance on her. In the etching, a sweet smile on her face conveys adoration and tenderness, an indication that he felt she could be trusted with this power implicitly.

There are only a few prints in the Suite Vollard that are composed entirely in drypoint. Picasso favored the technique in his early prints, but by the mid-1930s, he worked primarily in etching. His use of the drypoint here thus represents a distinct choice and an extremely sophisticated level of artistic discernment. The action of the needle carving directly into the plate results in somewhat staccato lines that underscore the raw emotional quality of the image. In addition, the burr of metal that is displaced to the surface results in a velvety black line that enhances the tactility of the beast’s pelt, emphasizing his animal nature.

Also apparent in this image is the influence of Rembrandt, whose outrageous personality features in four earlier plates of the series. Rembrandt was a master of all intaglio techniques, often combining etching with drypoint. Those impressions that include burr from the old master’s drypoint needle are particularly highly prized (an untreated burr wears down quickly, after about thirty impressions, and the steelfacing process was not invented until the nineteenth century). Picasso’s use of drypoint here shows a similar level of mastery with the technique. In addition, like Rembrandt often did, Picasso uses stark contrasts of light and dark (chiaroscuro) to punctuate the composition and draw out its inherent dynamic of good and evil.

The current impression is from the edition of 260 printed on Montval laid paper watermarked “Vollard” and “Picasso”. (There was also an edition of fifty with wide margins and a separate watermark, and a small edition of three.) It was printed by Roger Lacourière in late 1938 or early 1939. The untimely death of Ambroise Vollard in the summer of 1939 delayed their commerce until 1948 when the prints were acquired by dealer Henri Petiet through the Vollard estate.

i Françoise Gilot, Life with Picasso, Virago Press, 1990 [reprint of 1964 McGraw-Hill edition], 42.