As its title indicates, this print shows a sculptural rendition of the head of Marie-Thérèse Walter (1909-77), Picasso’s great love of the late 1920s through the 1930s and the inspiration of some of his most powerful works in all media. In the words of Walter’s grand-daughter, the art historian Diana Widmaier Picasso, ‘Through, with and around Marie-Thérèse, Picasso tapped into an unparalleled source of combined attributes in order to produce an exceptional profusion of works that constitute one of the most astonishing periods within his entire oeuvre, and in fact within twentieth-century artistic creation and art history in general’ (John Richardson and Diana Widmaier Picasso, Picasso and Marie-Thérèse: L’Amour Fou, exhibition catalogue, Gagosian Gallery, New York 2011,p.61).

Picasso met the seventeen-year old Marie-Thérèse in 1927, when he was forty-five, and was immediately smitten. After modeling for him for a short period, the young woman soon became his mistress, her sweet, docile nature and voluptuous sensuality providing incalculable relief from the psychic stress and stifling respectability that his failed marriage to the Russian ballerina Olga Kokhlova (1891-1955) had imposed on his life. Contriving to have his young mistress within reach as he traveled with his wife and son from Paris to beach resorts in the north and south of France, Picasso became ever more obsessed with Walter’s full-figured, athletic body, which generated the archetypal gigantism of the figures often combining male and female genitalia in single forms that he depicted in his beach paintings of the late 1920s. In 1932 these were hailed by the artist’s dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler as pioneering a whole new style, ‘neither Cubist nor Naturalist … but belong[ing] to an eroticism of giants’ (quoted in Widmaier Picasso, p.63). But perhaps even more significant was the effect of Marie-Thérèse on his sculpture. After setting up a studio in the vast stable block of the Château de Boisgeloup sixty miles north of Paris, during 1931 to 1934 Picasso produced more sculpture than in any other period of his life, translating his lover’s statuesque figure into monumental busts that fuse male and female attributes in tactile modeled forms. The artist Françoise Gilot (Picasso’s mistress from the early 1940s to the early 1950s) met Marie-Thérèse in 1949 and was struck by her appearance: ‘I found her fascinating to look at. I could see that she was certainly the woman who had inspired Pablo plastically more than any other. She had a very arresting face with a Grecian profile … Her form was very sculptural, with a fullness of volume and a purity of line that gave her body and her face an extraordinary perfection.’ (Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake, Life with Picasso, Virago Press, London 1964, p.224.) During 1931 in particular, Picasso began working with massive volumes of plaster, creating a series of Têtes de Marie-Thérèse that become increasingly pared-down accretions of sensuous bulbous forms (reproduced in Richardson and Widmaier Picasso, pp.134-55). In this he was doubtless inspired by the mother goddess statuettes from the Neolithic period, in particular the famous prehistoric Venus of Lespugue, a female figure made up of clusters of heavily rounded forms, of which he owned two plaster casts.

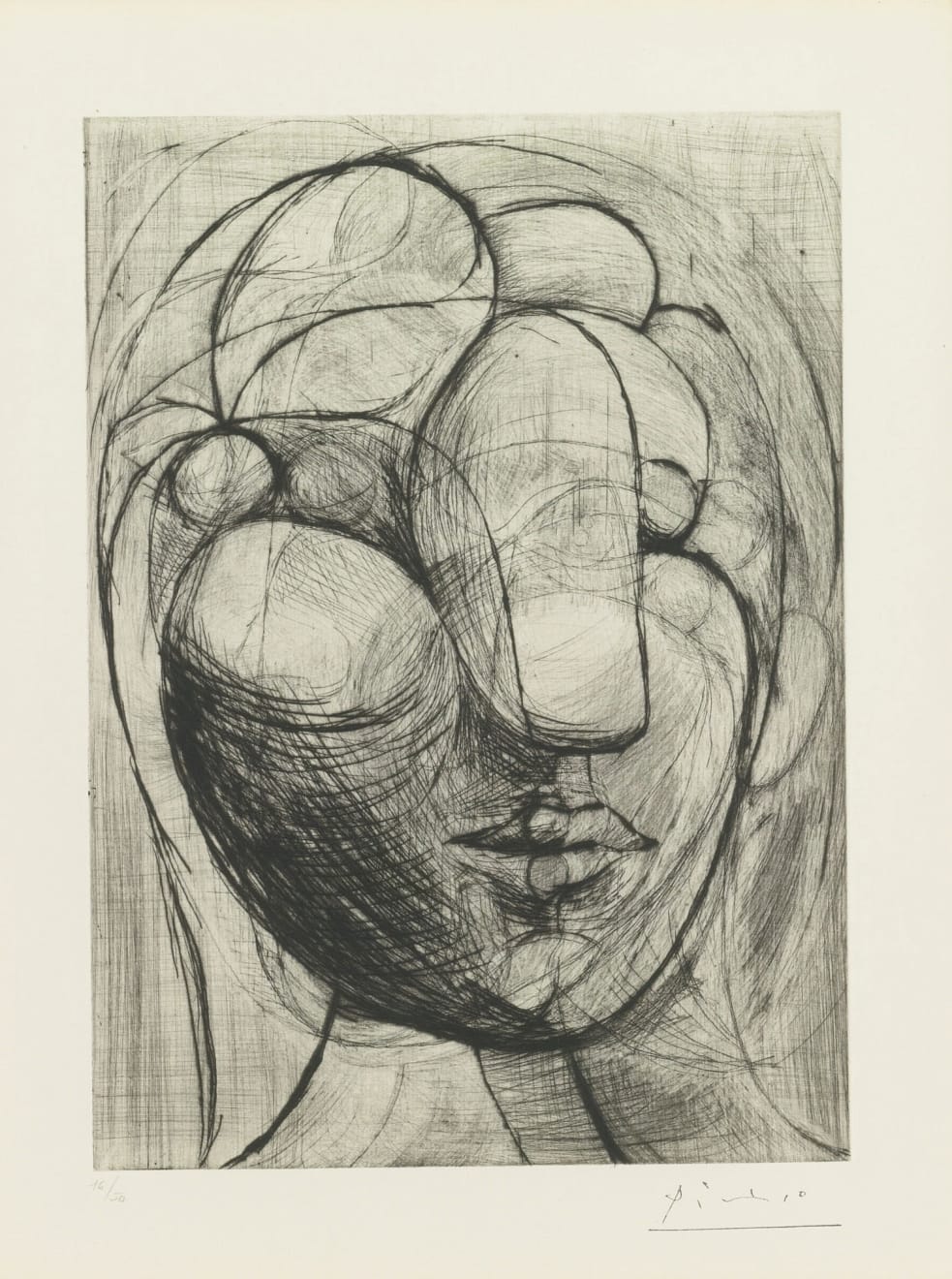

The evolution of this pioneering new style, in which physical volume swells taut with sexual desire, is documented and evoked in the progression of the twenty states of the artist’s drypoint, Sculpture, Tête de Marie-Thérèse created on February 16-18, 1933 in Paris. Beginning with a profile view of his mistress’s face made up of fine parallel lines, over the first five states Picasso refined his modeling to create increased volume in the globular forms of cheek, eye, forehead and lips that bulge out of the page in tandem with her ever more phallic nose as he filled the background with cross-hatching. In the sixth state, he made a dramatic change, partially cleaning the plate and turning Marie-Thérèse’s face to combine her profile with a full-frontal view, that while still volumetric has a flattened quality reminiscent of a sculptural frieze. In this and the next state his lover’s eyes have naturalistic pupils while her nose has receded back into her face, but Picasso quickly became dissatisfied with this permutation which clearly has lost the roundness that so evoked his sense of Marie-Thérèse’s form. In the eighth state he effaced almost all of the previous one and redesigned his composition using only the contours of the original bulge of the eyebrow, the line of the cheek below it, the jaw and chin and the narrow, triangular neck. This new abstracted head has been turned to the front, but in the following state Picasso again rotated it – this time towards the right – to create the basis for another more sculptural form. Composed of globular bulges both large and small, which at first appear to grow outwards and then to cluster around the central phallic protrusion that constitutes his subject’s celebrated Grecian nose, this face then evolved, becoming increasingly three-dimensional, over the following ten states before it reached its final form. Here, it combines Cubism (through the ghost of the profile) with Naturalism (in the full and tender lips) but with a sense of modeled, three-dimensional plasticity that abstracts the body very much in the Neolithic manner, as exemplified in Picasso’s numerous sculpted versions of this form.

Picasso himself pulled proofs of all the states of this composition during the course of working through them in 1933, but only the twentieth state was printed in any volume. In 1942 Roger Lacourière printed fifty-five proofs on Montval paper (watermarked Picasso or Vollard). Then in 1960 Jacques Frélaut pulled several trial proofs before printing seventy proofs on tinted Arches paper in 1961. Of these, fifty numbered impressions were editioned by Louise Leiris Gallery as part of the Caisse à remords in 1981.